Houston, still an energy town, largely pins growth on the sector

At Houston’s core, energy still rules. Two years after a COVID-19 lockdown helped collapse the energy sector and economic activity, historically high oil and gas prices and rising exports are propelling Houston ahead of the nation even as uncertainty and inflation erode the global economic outlook.

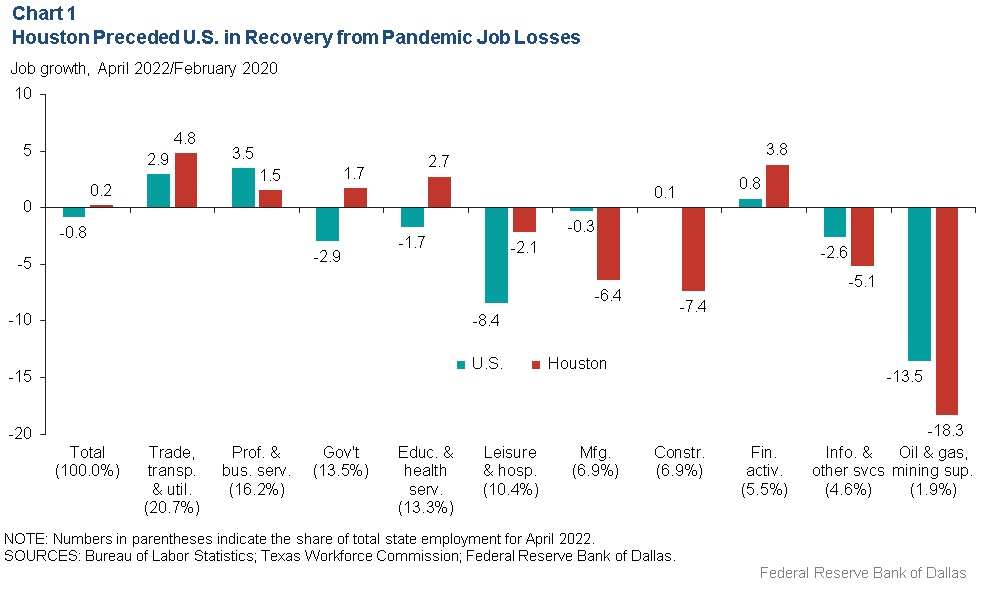

Some 25 months after the pandemic first struck, Houston has regained the 361,000 jobs that disappeared from February to April 2020 (Chart 1). Texas employment was 2.5 percent above its prepandemic level. By comparison, U.S. payrolls were 0.8 percent below prepandemic levels.

Apart from energy, the local service sector also suffered in the collapse, accounting for 330,000 lost jobs. Leisure and hospitality alone (especially restaurants) shed 134,000 positions, while trade, transportation and utilities (notably retail); professional and business services; and education and health services together lost another 138,000 jobs. Meanwhile, goods-producing sectors dropped 41,000 positions, more than half involving construction.

Houston, led by the service sector, initially declined more slowly than the U.S.; local employment fell 11.2 percent from February to April 2020 versus 14.4 percent in the U.S. By comparison, declines in area goods-producing industries continued into 2021.

Early in the pandemic, the energy downturn weighed on Houston manufacturing and construction industries. The fabricated metals industry, which produces components used by the oil and gas sector, slowed. Oilfield machinery, pipeline and related equipment, making up a large share of local machinery manufacturing, weakened. Construction sank, in part because of project cancellations and delays related to oil and gas mining, pipelines and petrochemicals.

Service industries in Houston—retail and wholesale trade and transportation, education and health, government, and financial activities—had surpassed prepandemic employment levels by April 2022. Nationally, education and health and government employment still had shortfalls. Texas’ decision to end pandemic restrictions on businesses earlier than most other states aided Houston’s leisure and hospitality rebound.

Energy Still Important

The pandemic underscored that Houston, despite diversifying since the 1980s, remains deeply connected to oil and gas.[1] The industry, with many of its biggest players headquartered in the metro area, accounts for more than one-third of Houston’s economy—including mining and refining as well as sizable segments of transportation, construction, manufacturing and services.

Energy’s direct share of the area’s GDP has averaged 7 percent over the past decade—even though very little oil and gas is produced locally. Nondurable goods manufacturing, mostly refining and petrochemical output, accounted for 13 percent of GDP, while durable goods manufacturing tied to energy accounted for another 3–4 percent. There are also spillovers to other industries, such as construction and engineering and legal services, as well as indirect impacts of spending by energy sector employees.

Despite energy’s large GDP impact, the employment share is relatively small. The industry is capital intensive, which means employment is relatively low but wages are high. From 2011 to 2020, it accounted for about 16 percent of Houston employment and 29 percent of wages paid.

Slow Shift to Growth

Even before the pandemic, U.S. fossil fuel producers struggled with poor rates of return on invested capital and dwindling access to funding. The 2020 oil demand collapse was devastating; global inventories of crude oil, gasoline and diesel swelled to historic levels and prices plummeted.

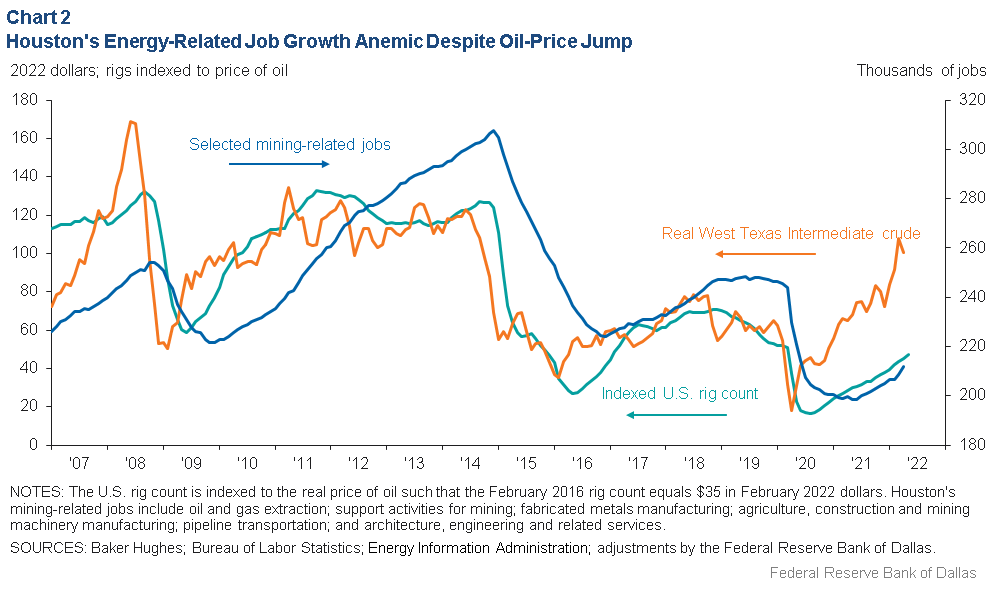

The West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil benchmark fell to negative $37 on April 22, 2020, meaning that producers paid to get rid of inventories. Oilfield activity fell 70 percent, and production from existing wells was in many cases capped or choked because there was nowhere to deliver product. One in five oil and gas mining jobs in Houston had disappeared by August 2020, though employment in the broader energy industry didn’t hit bottom until March 2021 (Chart 2). Bankruptcies surged.[2], [3]

As world economies began emerging from COVID-19 constraints in 2021, OPEC, Russia and other OPEC+ nations hewed to crude oil production growth limits; rising consumption drained oil stored from 2020. However, as inventories subsequently dwindled, OPEC+ producers couldn’t restore output as quickly as promised and oil prices pushed higher.

U.S. drilling tends to follow oil prices, but the industry’s response to rising real oil prices has been relatively lethargic since early 2021.

Before the pandemic, years of poor returns had sharply reduced access to capital from bond markets, banks and investors. The total return including reinvested dividends on Standard & Poor’s (S&P's) basket of exploration and production (E&P) firms was negative 50 percent from December 2012 to December 2020. The return on the broad S&P 500 was 209 percent.

Separately, $300 billion in energy debt was subject to bankruptcy proceedings in 2015 to 2021, according to the law firm Haynes and Boone. While some lenders abandoned energy, investors increasingly turned to alternative energy investments such as wind, solar and batteries.

Oil producers leaned on thousands of uncompleted wells in 2021 left from the pandemic-related collapse—wells that were drilled but not yet brought into production. This reduced the need to spend on drilling new wells. By year end, rising real energy prices, the limited spending and large dividends turned energy stocks from the worst-performing to the best-performing sector in the S&P 500. The bankruptcy cycle came to an end, and energy companies could again borrow through the bond market.

Still, the industry continued to cite investor demands for capital discipline and only modestly boosted spending on drilling and production activity. The reticence to spend has coincided with surging input prices for steel pipe, sand and machinery along with supply-chain delays and a very tight labor market. Thus, oil prices exceeding $100 per barrel may not generate the same level of stimulus for Houston as prior oil upturns would suggest even if elevated prices persist well past 2022, as currently expected.

Houston Exports Boom

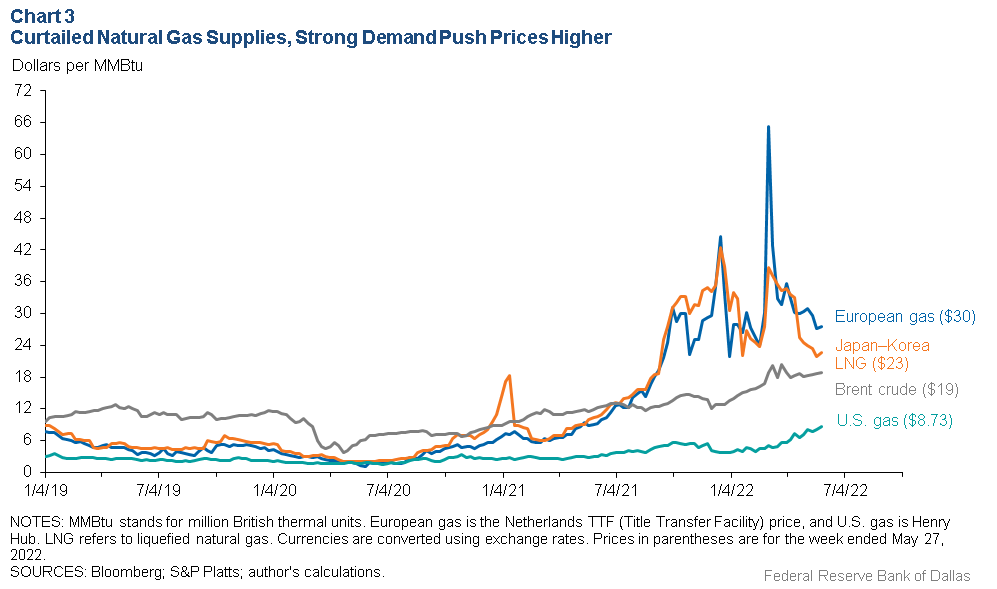

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in late February 2022 came at a time when European natural gas inventories were at perilously low levels dating back to early 2021 as Russia slowed deliveries. (Europe is a major purchaser of Russian natural gas).[4] The price of European gas rose from $7 per million British thermal units (MMBtu) at the start of 2021 to $30 in October 2021 and surged to $65 in the week following the invasion (Chart 3). Energy-hungry European buyers bid up liquefied natural gas (LNG) prices all around the world, including in the U.S.

U.S. benchmark Henry Hub natural gas rose to nearly $9 per MMBtu in May 2022 as moderate domestic supply growth met stronger domestic demand and growing LNG exports. A widening spread between U.S. and global energy benchmarks confers a cost advantage on U.S. firms with the capacity to export energy and energy-intensive products such as fuels and petrochemicals.[5]

Surging global demand for energy products has driven Houston exports to record highs. Chemicals, petroleum products, crude oil and natural gas make up three-quarters of the value of exports from the Houston–Galveston customs district, which extends along the Texas coast from Galveston and the Houston Ship Channel to Corpus Christi.

In the near term, the price differentials for natural gas will support elevated petroleum chemical product exports—to the extent supply chains can accommodate them. Spurred by sanctions against Russia and a desire to speed the energy transition to more carbon-neutral fuels, nations are moving to diversify sources of natural gas while displacing coal as an energy source. This would favor new investments in LNG capacity along the Texas coast, boosting heavy construction, manufacturing, logistics and support services for several years.

U.S. Economic Drivers

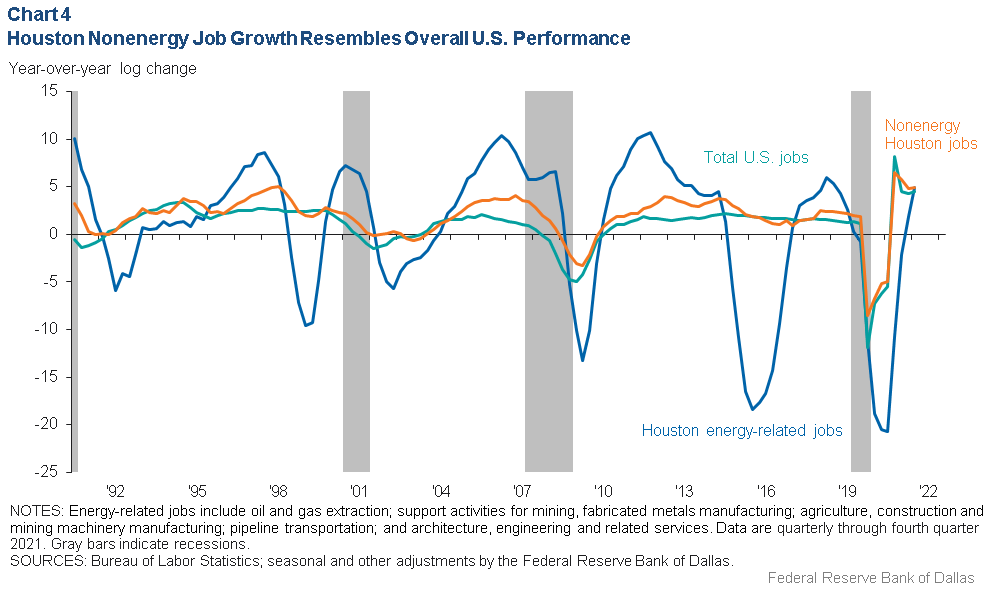

Outside of its oil and gas booms and busts, the Houston economy tends to be more closely correlated with the national economy (Chart 4).

Employment in Houston’s nonenergy sectors has grown at a 2 percent average annual pace over the past decade, while U.S. employment has expanded at a 1.3 percent rate. The area’s nonenergy jobs had in aggregate fully recovered to prepandemic levels by March 2022. with its annual performance resembling the rest of Texas and rarely falling below U.S. growth rates.

Professional and business services, education and health services, and leisure and hospitality are major drivers apart from energy.[6]

U.S. Economy Slowing

Energy-producing regions such as Texas tend to benefit from higher oil and gas prices, while most of the rest of the U.S. does not. At the same time, U.S. economic slowing will diminish some of Houston’s momentum.

The Blue-Chip Economic Indicators consensus of economic projections for the U.S. economy—an average of many forecasts—suggested in May 2022 that U.S. real (inflation-adjusted) GDP would slow from the 5.5 percent year-over-year rate in fourth quarter 2021 to 1.5 percent at year-end 2022. The latest forecast is sharply lower than the 2.9 percent 2022 growth anticipated in the February estimate.

Factors figuring in the reduction included a weak estimate of first-quarter GDP, rising interest rates, worsening supply-chain issues and inflationary pressures.

Rather than seeing Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation slow from 7.0 percent in late 2021 to 3.3 percent in 2022, the consensus panel in its May projections anticipated inflation exceeding 6.0 percent between fourth quarter 2021 and fourth quarter 2022. Longer term, forecasters anticipated that inflation wouldn't fall into the Federal Reserve’s target range of 2–2.5 percent until 2024.

Meanwhile, job forecasts have accelerated on stronger-than-expected job growth. The Survey of Professional Forecasters (SPF) projection for U.S. job growth in 2022 reached 2.8 percent from 2.6 percent. Similarly, the Dallas Fed’s May projection for 2022 Texas job growth increased robustly to 3.7 percent from 3.0, in part because of higher energy prices. In both the U.S. and Texas, the pace of growth through year-end is likely to slow.

Houston to Outperform

The drag on consumers from high fuel prices is more than offset in Houston by spending in oil and gas and related sectors. However, energy firms’ expenditures are expected to remain moderate compared with past episodes of high energy prices, limiting their impact. At the same time, exports of natural gas are likely to rise, supporting related investments for several years and giving Houston job growth a bit of a tailwind.

If recent projections for the U.S. prove accurate and energy prices remain elevated as anticipated, Houston payroll growth should outpace the national rate of 2.8 percent this year and could outpace the state. Thus, Houston should do well absent an unexpected, large increase in energy supplies, a negative demand shock such as a recession or a new, widespread COVID-19 outbreak.

Notes

- “Diversified Houston Spared Recession … So Far,” by Jesse Thompson, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Southwest Economy, Third Quarter, 2015.

- “Go Figure: COVID-19 Tanks U.S. Fuel Consumption, Prices,” by Jesse Thompson and Olu Eseyin, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Southwest Economy, Second Quarter, 2020.

- For related information on the impact of the pandemic on the energy sector, see Energy Indicators, by Jesse Thompson, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, May 2020 and June 2020.

- Energy Indicators, by Jesse Thompson, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, January 2022.

- “Booming Shale Gas Production Drives Texas Petrochemical Surge,” by Jesse Thompson, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Southwest Economy, Fourth Quarter, 2012.

- Houston–The Woodlands–Sugar Land: Texas’ Gulf Coast Hub and Nation’s Energy Capital,” At the Heart of Texas: Cities’ Industry Clusters Drive Growth, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, December 2018.

About the Author

Jesse Thompson

Thompson is a senior business economist in the Houston Branch of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

Southwest Economy is published quarterly by the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.

Articles may be reprinted on the condition that the source is credited to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

Full publication is available online: www.dallasfed.org/research/swe/2022/swe2202.