Mexico awaits ‘nearshoring’ shift as China boosts its direct investment

When it comes to trading goods with the United States, Mexico would appear a logical sourcing alternative to China. Before the pandemic, increasing tariffs on trade between the U.S. and China—the top supplier of goods imports to the U.S.—contributed to anticipation of a “nearshoring” shift among companies dependent on Asia.

Subsequent COVID-19-era global supply-chain disruptions only increased the expectation of burgeoning activity in Mexico, which has benefited from free-trade accords with the U.S. dating back to the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994.

Anecdotal media reports suggest that the nearshoring move to Mexico is at hand, while hard data provide no such conclusive evidence. Anecdotal accounts include a Banco de México survey published in September 2022 in which 16 percent of respondent firms indicated they had benefited from nearshoring trends in the prior 12 months. A separate Citibanamex analysis of Mexican industrial properties cited nearshoring as contributing to low industrial vacancy rates of around 5 percent nationally and to zero along the border in Tijuana.

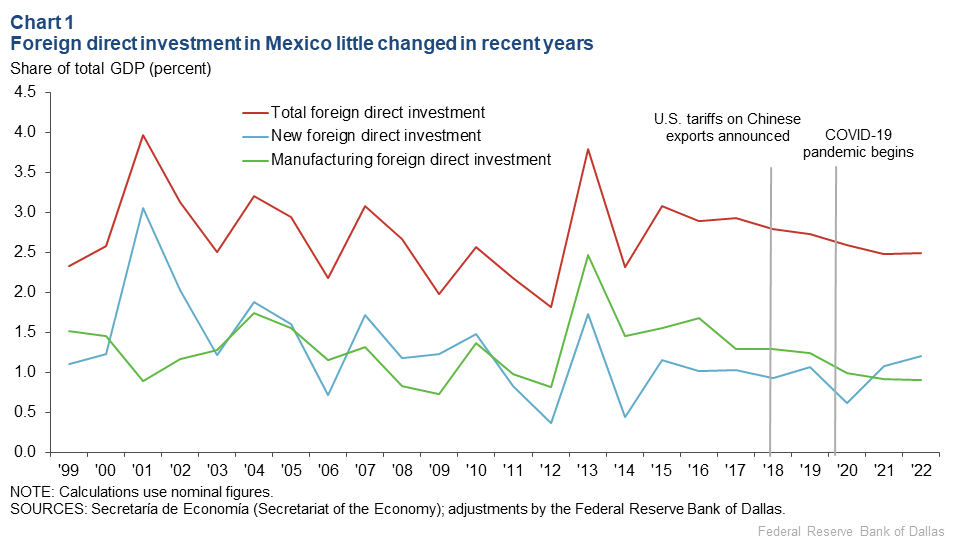

Nearshoring to Mexico should be reflected in foreign direct investment (FDI) data. But FDI in Mexico was largely flat from 2015 to 2022 (Chart 1). It could be because large sums are often involved; the impact on FDI is lagged and may well show up in future data releases. It could also be that other factors—such as a changing business climate or the pandemic—have held up progress on nearshoring to Mexico.

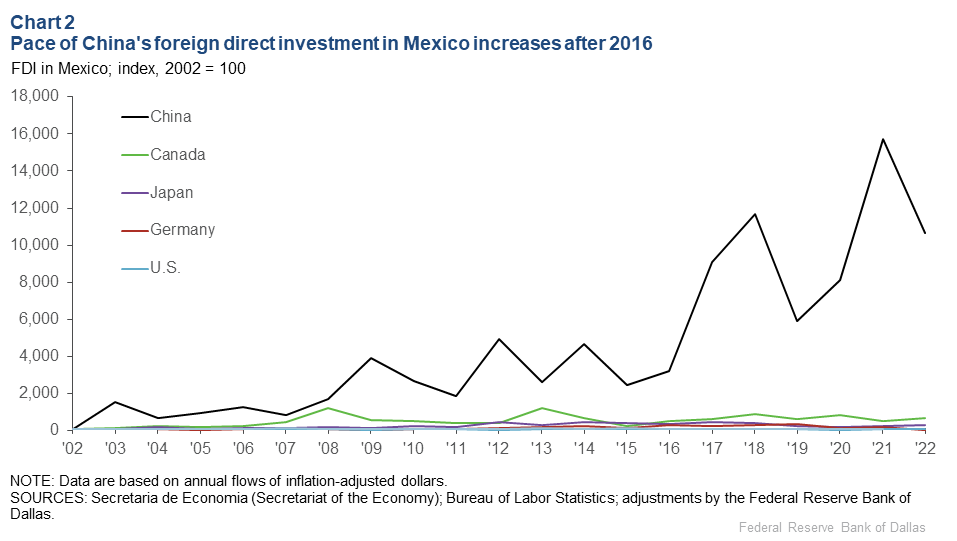

Nearshoring would imply that U.S. companies are moving operations or suppliers from overseas to Mexico and nearby countries, presumably boosting FDI. So far, the U.S. share of FDI in Mexico is little changed, while China’s share—though still very small—is rising quickly (Chart 2).

Several factors may explain these developments. Sharply higher tariffs since 2018, owing to U.S.–China trade tensions, along with supply-chain difficulties during the pandemic likely increased Chinese companies’ incentives to invest in Mexico.

Additionally , the U.S.–Mexico–Canada trade accord (USMCA), which took effect in July 2020 and replaced NAFTA, may have limited some anticipated FDI benefits. The USMCA imposed more restrictive conditions on some cross-border activity than its predecessor, reducing trade gains. Moreover, the investment environment was especially uncertain given the USMCA’s pandemic-era launch and changes in Mexico government policies.

Origins of foreign investment in Mexico

Mexico has been an attractive FDI destination in recent decades, accounting for about 25 percent of FDI in Latin American and Caribbean countries in a typical year. Mexico’s main draw is access to the U.S. and Canada via geographic proximity and USMCA preferential tariffs. (Mexico also has trade agreements with 48 other countries.)

Mexico's plentiful labor supply and relatively low wages also make it a cost-effective location for high-cost countries to outsource production. Mexico’s large internal market and growing retail and financial services sectors are also draws for foreign investors. U.S. firms such as Walmart and H-E-B and Spain-based banking company Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria (BBVA) have extensive operations in Mexico.

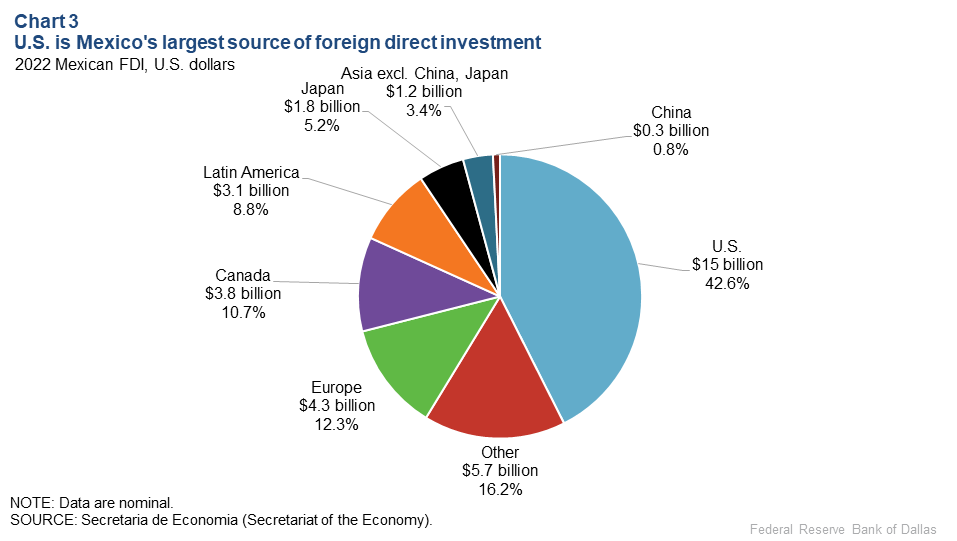

Historically, the U.S. has accounted for nearly half of FDI in Mexico, indicative of the two countries’ highly integrated trading relationship. U.S. companies invested $15 billion in Mexico's economy in 2022. Mexico's other top sources are European countries that together invested $4.3 billion. The largest FDI inflows from Europe were from the United Kingdom and Spain, each totaling $2 billion. Canada accounted for $3.8 billion, followed by Argentina, $2.3 billion, and Japan, $1.8 billion (Chart 3).

Auto sector dominates Mexico FDI

The Mexican manufacturing sector has been the target for 47 percent of U.S. investment, of which the automotive sector accounted for roughly one-third of those outlays, or $3 billion.

The U.S. auto industry relies heavily on parts produced in Mexican maquiladoras—plants that produce primarily for export. Among Mexico’s other top foreign investors, Japan also maintains a large automotive manufacturing presence. (Meanwhile, Canada is active in metallic mineral mining and natural gas pipelines, the U.K. in beverage manufacturing and wholesale, and Spain in financial and insurance services.)

Most motor vehicle parts produced in Mexico are for foreign markets and include such global brands as General Motors, Ford, Honda, Hyundai, Kia, Toyota, Mercedes-Benz and Nissan. Additionally, nine out of 10 vehicles made in Mexico are exported.

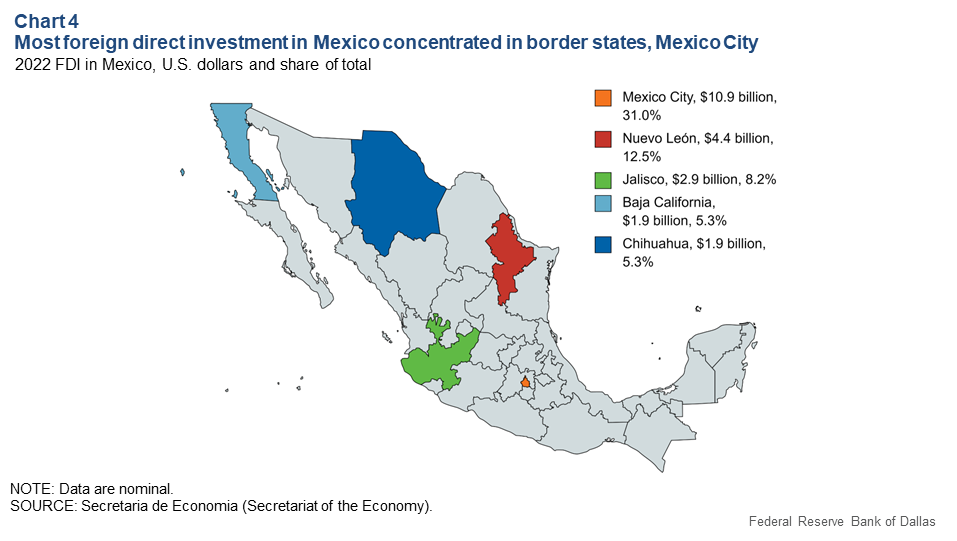

The auto sector is reflected in the foreign direct investment concentrated along the Mexican border states of Nuevo León, Baja California and Chihuahua (Chart 4 ). Given the cross-border supply linkages and geographic proximity to the U.S., producers can save on transportation costs and bolster supply-chain efficiency.

The concentration of investment in Mexico’s automotive sector is evident in overall FDI inflows. Manufacturing captured 36 percent of FDI in 2022—of which automotive manufacturing attracted 8 percent and automotive parts another 4 percent. Transportation and warehousing accounted for 15 percent of FDI and financial and insurance services 13 percent.

Mexico’s export destinations mirror its top foreign investors—82 percent of exports were sent to the U.S. in 2022, followed by Canada (3 percent), China (2 percent) and Germany (1 percent). About 42 percent of U.S. motor vehicle parts imports came from Mexico in 2018–22. (Apart from auto parts and autos, Mexico’s top exports are digital processors, crude oil and televisions.)

Growth in China FDI

China FDI flows into Mexico grew on a nominal basis from $38 million in 2011 to $386 million in 2021 before slipping last year to $282 million—still well above its historical average. While China represents only about 1 percent of Mexico's FDI, the country has significantly expanded its investments and is the fastest-growing source of foreign investment in Mexico.

This FDI investment is mostly directed toward manufacturing plants and regions that export to the U.S. The majority of China FDI flowed to computer equipment manufacturing—approximately $213 million in 2021 and $69 million in 2022. For example, Lenovo announced an initial $20 million computer plant investment in 2007 in Monterrey, which in 2021 nearly doubled to include server and computer rack assembly at what Lenovo calls its “megasite.”

Computer equipment exports from Mexico to the U.S. accounted for 13 percent of all U.S. computer imports on average in 1999–2017 before jumping to 25 percent in 2018–22.

Most of China’s FDI during 2021–22, $242 million, was in the northern state of Chihuahua, followed by $216 million in Mexico City and $78 million in Nuevo León.

U.S. tariffs help motivate investment

Several factors may explain China’s growing interest in Mexico investment. Its investment primarily involves industries and locations that export to the U.S. and appears linked to comparatively higher tariffs on China’s imports into the U.S. and to supply-chain disruptions.

Additionally, some global companies may have redirected investment from China after its zero-COVID policies intermittently shut down portions of the country for almost three years, significantly disrupting production and commerce. Reliability, resiliency and security of production locations and supply chains have become more important due to the pandemic and concurrent geopolitical tensions.

In 2018, the Trump administration applied a series of tariffs on imports from China, which retaliated with levies on U.S. exports.

Approximately $335 billion worth of trade, representing 66 percent of U.S. annual imports from China, remains subject to tariffs, according to the Peterson Institute for International Economics. The average U.S. tariff on imports from China—19 percent—is more than six times 2018 levels. By comparison, China’s tariffs on U.S. exports average around 21 percent.

The tariffs on China’s goods have, in turn, made imports from other countries such as Vietnam and Mexico more competitive—a disadvantage that China can mitigate with relocations to Mexico.Supply-chain disruptions motivate production moves

China's COVID-related lockdowns, movement restrictions and supply shortages contributed to global supply-chain disruptions during the pandemic, a time when goods demand surged. China’s economic activity slowed with the pandemic’s onset in first quarter 2020, causing a backlog of unfilled orders of manufactured goods and delayed shipments of manufactured goods.

Supply-chain problems grew worse when shippers ran out of containers and the means to transport them to and from seaports, whether by truck or train.

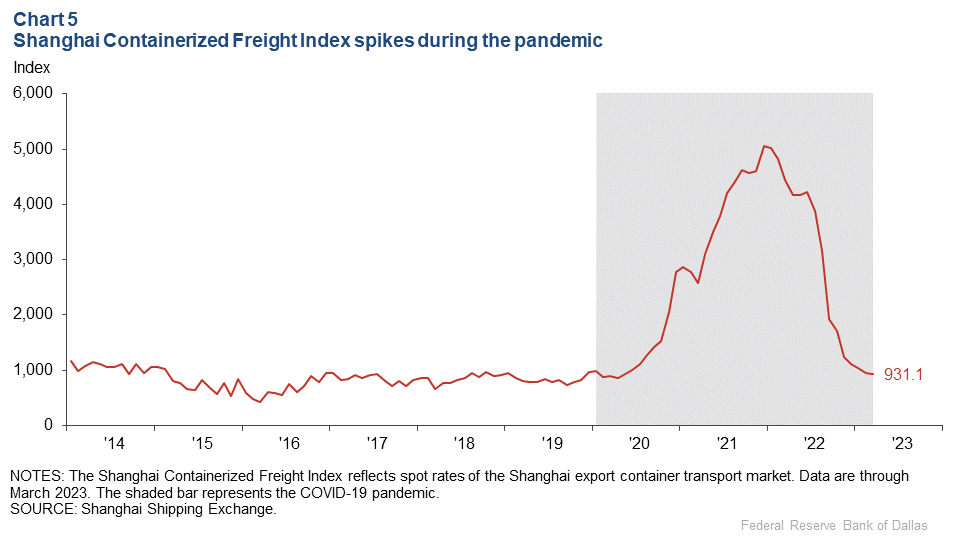

The Shanghai Containerized Freight Index, which reflects the cost of shipping containers from Shanghai to foreign ports, reached 4,819 in February 2022, from 2,775 in February 2021 and 876 in February 2020, just before the onset of COVID (Chart 5).

Freight costs have receded in recent months to near prepandemic levels.

In December 2022, China rolled back its zero-COVID restrictions, leading to a surge in cases and renewed supply-chain vulnerability. In one instance, reports indicated that on some days, 20–30 percent of employees at China’s largest electric vehicle manufacturer, BYD, were home sick, leading to a production cut of 2,000 to 3,000 vehicles per day.

Benefits of foreign direct investment

Nearshoring could alter Mexico’s foreign investment landscape. While China has boosted FDI, Mexico has yet to see any sustained growth of such inflows from other countries. Moreover, it’s unclear whether China’s investment increase was due to companies trying to maintain access to the U.S. market or if that investment had been planned before the twin shocks of higher tariffs and pandemic limitations.

More generally, through its Belt and Road Initiative begun in 2013, China has invested in infrastructure, economic development and trade around the world, becoming a global source of FDI. Net FDI outflows from China represented 4 percent of world FDI outflows in 2013 before jumping to 22 percent in 2018. They declined to 6 percent in 2021.

Foreign investment in Mexico boosts economic growth through job creation, incentives for human capital development and technology transfers. Along the U.S. border, such investment spurs growth in U.S. service sector industries that complement manufacturing production and international trade—notably transportation and logistics, warehousing, accounting, finance and commercial real estate. More broadly, Mexico, the U.S. and Canada stand to benefit due to the greater integration of production across the region and the resulting increase in international competitiveness.

FDI is especially important when domestic investment is lacking. Public investment in Mexico has stagnated, representing 3 percent of GDP in 2021, below its historical average of 4 percent. Also, cancellation of a new international airport in Mexico City in 2019 depressed private sector investment amid concerns about the federal government's economic policies and the country’s worsening security and crime situation.

Such negative factors have to be weighed against positive developments, such as prudent monetary and fiscal policy. Mexico’s central bank has been aggressive in fighting the pandemic-era surge in inflation, while the federal government has kept the country’s debt levels stable and the public deficit relatively small.

No free lunch

Rising geopolitical tensions, barriers to trade and the pandemic have influenced investment decisions and the movement of goods around the world. The resulting investment and trade distortions may be necessary for national security or supply-chain resiliency, but they come with a cost by creating inefficiencies in the use of capital, labor and technology and resulting in the production of goods at a relatively higher price.

Under free trade, countries specialize in producing goods where they hold a comparative advantage as determined by factors of production—capital and labor—and technology. This practice benefits consumers by offering relatively lower prices and more product choices. Even though nearshoring creates benefits for the U.S. and Mexico, consumers will bear higher costs.

About the authors

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.