China remains modest player in U.S.–Mexico trade despite growing scrutiny

Mexico, the largest trading partner of the United States, has expanded its trade linkages with China and East Asia in recent years. This has raised questions about whether Mexico is becoming a backdoor for exports to the U.S. market. However, data tell a more nuanced story of Mexico’s integration into global value chains, with deep supply links to the United States.

Mexico became the largest source of goods imports to the U.S. in 2023, accounting for 15.5 percent of U.S. goods imports in 2024. Its gains have come amid continued U.S.–China trade tensions, highlighted by imposition of tariffs in 2018–19 and again in 2025.

Meanwhile, China’s exports to Mexico ballooned, reaching 21 percent of Mexico’s imports, creating a trade surplus of almost $120 billion in 2024. Concurrently, Mexico is also a growing end market for Chinese consumer goods exports, consistent with a broader shift of China’s exports toward emerging economies globally.

These trade shifts have raised concerns about Chinese exports reaching the U.S. market through Mexico. The changes are also a potential focus of U.S. government policy, as a review of the U.S.–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA) trade pact begins later this year.

Import growth from East Asia (outside of China) has accelerated in Mexico, as the region integrates its economy into global value chains, particularly involving electronics. This has shown up in more Mexican exports of advanced technology products to the U.S., with Mexico set to exceed China as the largest source of such imports to the U.S. in 2025.

Concurrently, U.S. exports to Mexico have also risen significantly in the past several years. Some of it subsequently shows up in the many Mexican exports with substantial U.S. content. This development underscores a deep trading relationship involving closely integrated supply chains, among them many with Texas ties.

Understanding Mexico’s evolving economic linkages with East Asia and China is critical to the future of the USMCA and the nearshoring and integration of North American manufacturing supply chains.

China’s declining U.S. import share

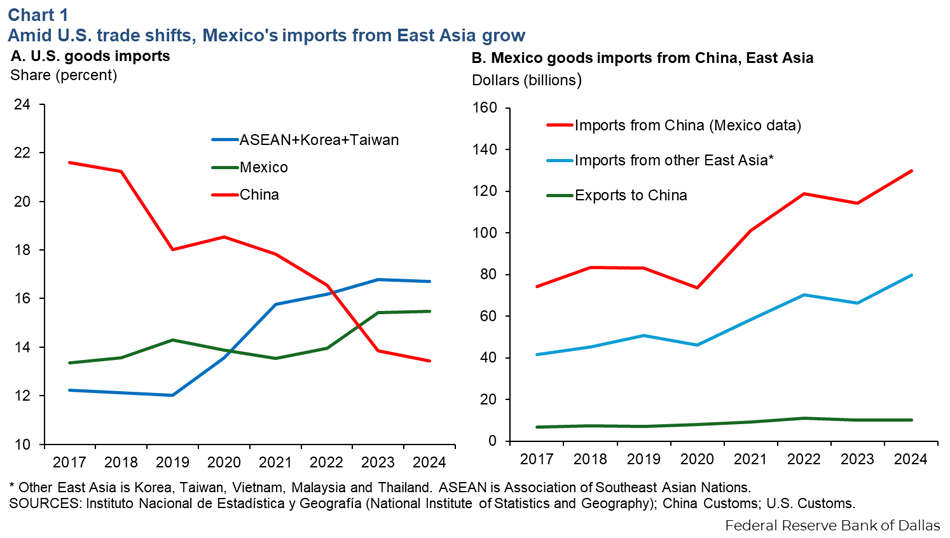

Bilateral trade between the U.S. and China rapidly expanded following China’s 2001 accession to the World Trade Organization. China became the largest source of U.S. imports in 2009, peaking at 21.6 percent of U.S. imports in 2017. The share fell to 13.4 percent in 2024, according to Bureau of Economic Analysis data, though Federal Reserve Bank of New York researchers found this decline to be overstated.

Over the same period, U.S. imports from Mexico and other emerging economies have continued to rise, often alongside growing intermediate goods imports from China—pointing to a broader reconfiguration of U.S. supply chains rather than U.S.–China decoupling.

Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) economies picked up the greatest U.S. import market share, rising from 7.3 percent in 2017 to 10.8 percent in 2024, while Taiwan advanced from 1.8 percent to 3.6 percent, and Korea inched higher from 3.1 percent to 4 percent, according to U.S. customs data (Chart 1A).

ASEAN’s goods trade surplus with the U.S. rose rapidly, reaching $228 billion in 2024; its imports from the U.S. simultaneously grew much less, totaling $124 billion last year.

Mexico’s share of U.S. goods imports rose 2.1 percentage points, from 13.4 percent in 2017 to 15.5 percent in 2024. Overall, U.S. goods imports from Mexico increased from $346 billion in 2018 to $506 billion in 2024. Meanwhile, Mexico’s trade surplus with the U.S. more than doubled from $81 billion to $172 billion over the period, based on Census Bureau data.

Mexico’s growing imports from China, East Asia

China–Mexico trade has grown rapidly, with China’s exports to Mexico rising from $74 billion in 2017 to almost $130 billion in 2024, according to Mexico trade data. The trade relationship is largely one-sided; Mexican exports to China have hovered around $10 billion in recent years (Chart 1B).

Mexico’s supply chain integration with Asia is much broader than its ties with China. Mexico’s imports of electronics and other products from other East Asian economies (particularly South Korea and Taiwan, and to a lesser extent Vietnam, Malaysia and Thailand) have expanded Mexico’s role in the broader global technology value chain.

Mexico’s exports to the U.S. grow as supply chains evolve

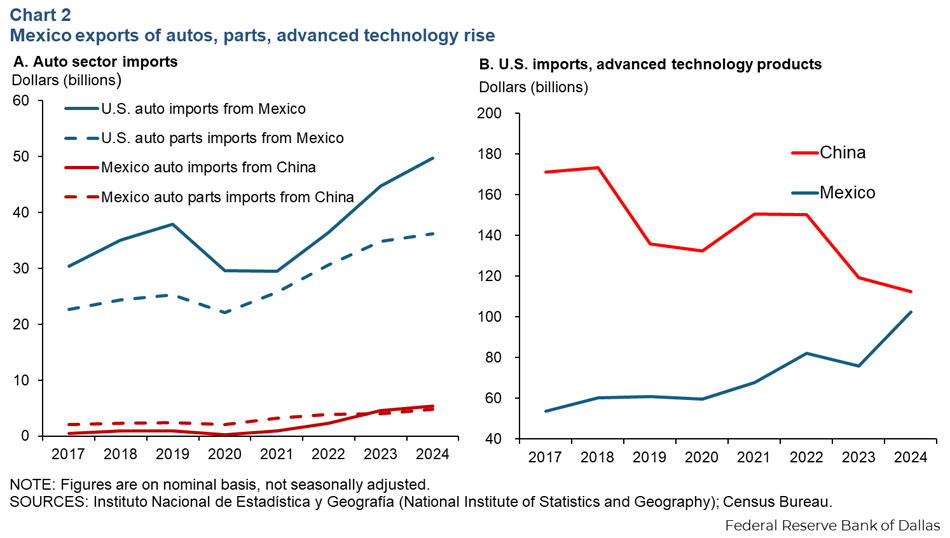

The automobile sector (vehicles and parts) is responsible for much of the rise in U.S. imports from Mexico. Advanced technology products (as classified by U.S. customs), such as electronics, machinery and advanced information and communications products, also significantly contributed.

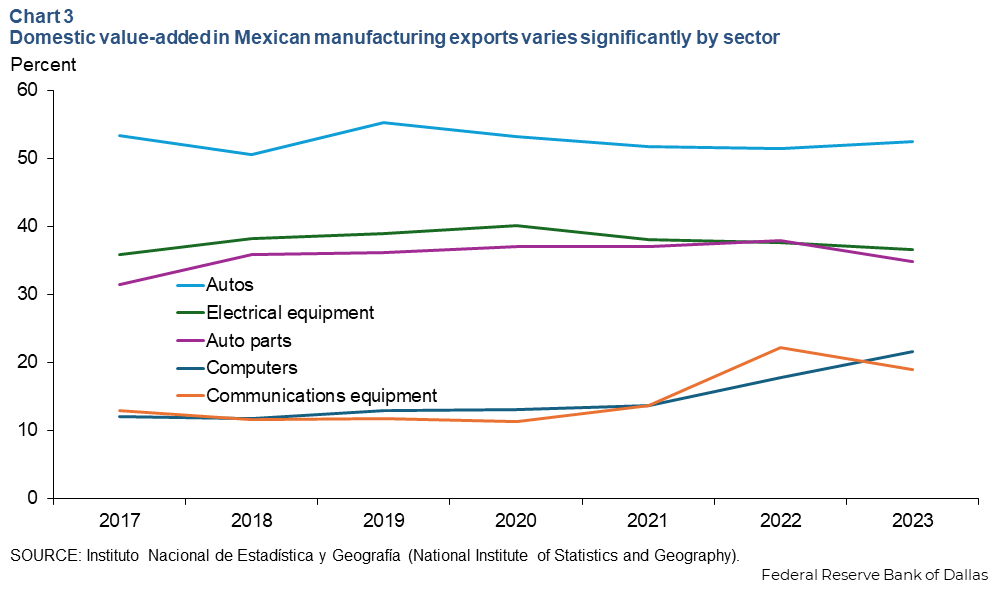

While Mexican imports from East Asia, particularly intermediate goods, support this increase, manufactured goods exported from Mexico to the U.S. contain significant value added in Mexico. The most recent Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) data on trade in value-added show an estimated 51 percent domestic value-added in Mexican manufactured goods exports to the U.S. Domestic value added essentially measures the portion of an export's value that originates domestically, reflecting the economy's contribution to the good’s production.

Mexico has long had a strong automobile and auto parts sector and a prominent role in the North American auto manufacturing value chain. While Mexican imports of vehicles and parts from China rose from $3.1 billion in 2017 to $13.5 billion in 2024, this increase does not appear to meaningfully contribute to Mexico’s growing auto sector exports to the U.S.

More than half of Mexico’s auto sector imports from China have been finished automobiles and trucks, reaching $5.3 billion and $1.2 billion, respectively, in 2024. These have been for Mexico’s domestic market, not for export. U.S. imports of auto parts from Chinese companies in Mexico have likely increased, though Mexico’s imports of auto parts from China rose only $2.8 billion from 2017 to 2024. (Chart 2A).

More notable has been the rapid increase in Mexico’s exports of advanced technology products—such as electronics and information and communications items (computers, phones, electrical appliances)—not a traditional source of strength. Such exports to the U.S. rose from $60 billion in 2018 to more than $102 billion in 2024, according to the Census Bureau. Mexico is poised to exceed China in terms of such exports to the U.S. this year (Chart 2B).

Mexico has a lower value-added in these advanced technology products than other goods (Chart 3). Much of the value-added content appears to come via imports from East Asian economies, based on OECD trade in value-added data.

Mexican value added in these sectors has increased modestly over the past several years from around 12 percent for computers and electronics in 2018 to about 20 percent in 2023, according to Mexico’s statistical agency (INEGI, its Spanish acronym). This contrasts with more than 50 percent domestic value-added in Mexico’s automobile exports. Mexican value-added in semiconductors was only 16 percent in 2023.

The Mexican government’s economic development blueprint, Plan Mexico, aims to increase domestic content 15 percent in the electronics and automotive sectors as well as in other areas. The program, with a 2030 target date, seeks to broaden the benefits to the Mexican economy while addressing U.S. concerns that Mexico is a backdoor for Chinese and Asian exports to the U.S.

U.S. imports from Mexico also contain significant U.S. domestic value added, 17 percent for all manufactured goods and 20 percent in the auto sector, based on OECD trade in value-added data. The U.S. contribution is indicative of coproduction and underscores the supply chain linkages between the two economies. This coproduction is particularly notable between Texas and Mexico.

By comparison, analysis of data from the Asian Development Bank finds that value-added content from China accounts for roughly 7 percent of the value of Mexico’s goods exports to the U.S.

Mexican officials have emphasized that U.S. companies in Mexico account for a substantial portion of Mexico’s imports from China and East Asia. There is a growing awareness, supported by anecdotal evidence, that a portion of Chinese exports to Mexico may involve multinational firms—particularly U.S. ones—expanding their operations in Mexico while continuing to rely on established suppliers abroad, including those based in China. This pattern would be consistent with supply-chain strategies aimed at combining the benefits of proximity to the U.S. market with the cost advantages or specialization of existing foreign input sources.

These imports support some nearshoring of U.S. supply chains, as U.S. companies have increased their focus on supply chain resiliency and security following pandemic-related disruptions and geopolitical tensions. Banco de Mexico analysis finds little evidence of pure re-exports (a Chinese company bringing a product to Mexico and then exporting it to the U.S.).

The importance of the U.S. working with Mexico on supply chain security concerns regarding China will increase as Mexico plays a growing role in U.S. information and communications technology supply chains. This may include greater rulemaking under the U.S. Commerce Department’s information and communications technology and services authority.

China sales to Mexican consumers rise as exports shift to emerging markets

China’s exports to Mexico go beyond supply chain considerations. Consumption goods imports from China have risen sharply, including smartphones, flat panel screens and vehicles. Chinese exports have shifted from developed economies to emerging markets, and Mexico, along with the rest of Latin America, is part of this trend.

While consumers welcome competitively priced Chinese goods, import surges of Chinese goods are disrupting domestic industries, leading to growing trade restrictions targeting China, including in Mexico.

International Monetary Fund analysis in 2024 found a steady shift toward more consumption goods in Mexico’s imports from China. Mexico’s import of final goods from China (particularly consumption goods, but also capital goods, such as machinery to support productive capacity), rose almost 6 percentage points as a share of Mexico’s overall imports from China from 2017 through 2023. The share of intermediate goods fell an equivalent amount. For example, smartphone imports from China have grown rapidly from a negligible level in 2020, reaching $5.6 billion in 2024, according to Banco de Mexico data.

China’s booming auto exports have gained the most attention—and scrutiny—globally over the past two years. China surpassed Japan as the world’s largest auto exporter in 2023. Mexico was China’s second-largest auto export market in 2024 (trailing only Russia), taking in 303,000 light vehicles.

Thus, China became Mexico’s largest auto supplier in 2024, ahead of the roughly 127,000 autos imported from the U.S. From a value standpoint, Mexico’s auto imports from China reached $5.3 billion, compared with $4.6 billion from the U.S. Mexico’s imports of auto parts from the U.S. still exceeded its imports from China by more than four times in 2024.

Over the past year, Mexico has stepped up trade investigations and restrictions targeting imports from China, mirroring trends globally. China’s imbalanced growth, characterized by very high investment levels and expansion of industrial capacity alongside weak domestic household consumption, has created record trade surpluses, approaching $1 trillion in 2024. Put into context, China’s manufactured goods trade surplus has reached over 2 percent of global GDP, which exceeds the combined surplus of Japan and Germany during their collective peak in the 1970s and 1980s.

Chinese exports to developing economies have grown particularly rapidly. Meanwhile, China’s import growth remains weak.

This has spurred a record number of trade investigations targeting China, with more than half of these cases from developing economies.

Mexico an important, growing U.S. export market

Lastly, the U.S. trading relationship with Mexico is more balanced relative to that with China or other East Asian economies. Mexico is the third-largest U.S. export market after the European Union and Canada. Together, Mexico and Canada absorb roughly one-third of U.S. exports.

Mexico imported more than 40 percent of its goods from the U.S. in 2024, almost three times the share of U.S. imports from Mexico. U.S. exports to Mexico have grown steadily in recent years, increasing from $244 billion in 2018 to $334 billion in 2024. The U.S. exported an additional $49 billion in services to Mexico in 2024.

The U.S. has lost some of its import share in Mexico, which exceeded 46 percent before 2018, to China and other East Asian economies. This trend has been most pronounced in the auto sector and in machinery.

As Mexico aims to lessen imports from China, U.S. exporters may ultimately have opportunities to regain market share. However, in the short term, Mexico is likely to face increasing pressure from Chinese exports, specifically, items redirected from the U.S., due to additional tariffs imposed by the U.S. on China since February 2025. The outcome of ongoing U.S. trade negotiations with other partners may also shift U.S. exports.

|

This article is part of a series examining China’s evolving trade and investment linkages with North America and the subsequent policy responses. The series will look at Chinese foreign direct investment in Mexico, the impacts of U.S. limits on Chinese imports and the prospects for nearshoring of North American supply chains. |

About the authors