Texas community banks grapple with national stresses as elevated rates pose new tests

Community banks have long been both a reflection of and a foundation for Texas’ economic strength. In the past year, these banks grew faster than Texas regional banks, despite the latter’s size advantage. The closures of Silicon Valley Bank and First Republic Bank in California and Signature Bank in New York in spring 2023 and a subsequent deposit drain across the country affected regional banks more severely than community institutions.

Despite community banks’ relative strength in Texas, the outlook through year-end 2024 comes with evolving downside risks, particularly involving unrealized losses on fixed-income holdings, such as Treasuries, and commercial real estate loans on projects suffering from weak postpandemic occupancy. These challenges have become more pronounced in the current higher interest rate environment.

Community banks lead in deposits, loans and assets

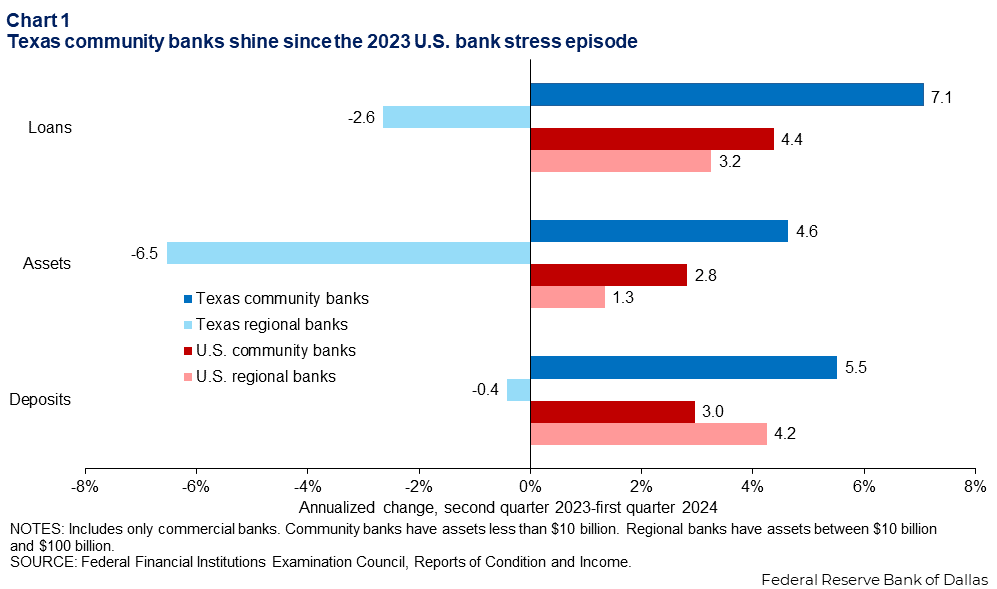

Texas community bank deposits grew (5.5 percent) from the second quarter of 2023 through the first quarter of 2024, while regional bank deposits dropped slightly (-0.4 percent) (Chart 1). Similarly, community banks grew their loans (7.1 percent) and assets (4.6 percent), but regional banks shrunk both loans (-2.5 percent) and assets (-6.5 percent).

In addition to outperforming regional banks in the state, Texas community banks outperformed U.S. regional and community banks in terms of loans, assets and deposits.

Texas community bank profitability ticked up in the first quarter of 2024, with return on average assets rising after declining in the second half of 2023. This reflects both Texas’ economic growth premium and the strength of community banks in the state.

Texas has most community banks of any state

Texas historically has been a community banking state; it has more community banks than any other state, around 370. (Illinois ranks second, with about 330 such banks). Community banks each have total assets of less than $10 billion, while regional banks hold total assets of between $10 billion and $100 billion.

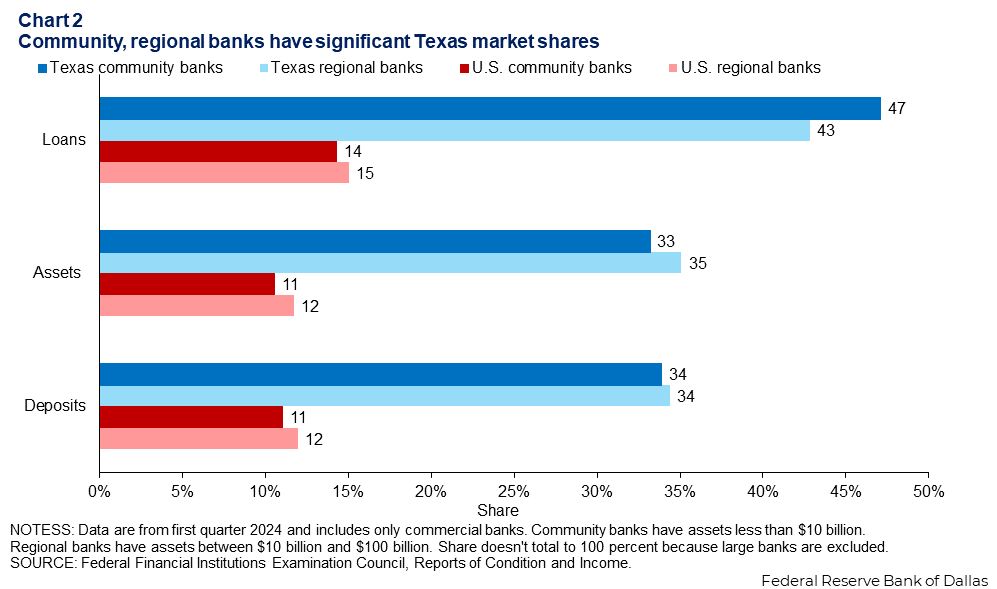

Among Texas banks, 99.7 percent were community banks in 2005. The share and number of community banks have declined nationally and in Texas, the share slipping to 97 percent in the state and U.S. Community bank presence in Texas remains strong, with an outsized share of deposits, assets and loans when compared with community banks nationwide. In Texas, they account for around 47 percent of loans, 33 percent of assets and 34 percent of deposits held by banks in the state (Chart 2).

Nationwide, community banks hold just 14 percent of all loans, 11 percent of assets and 11 percent of deposits. Unsurprisingly, the main reason for the difference is that the largest U.S. banks are not headquartered in Texas, but they maintain branches and lend in the state.

Risks lie ahead in an evolving economy

Since the Federal Reserve began raising its benchmark federal funds interest rate in Mach 2022, banks holding fixed-income assets such as Treasuries have incurred unrealized losses. (The value of bonds moves inversely to interest rates.) Additionally, liquidity has tightened as deposits have stagnated, and there are fewer funding options than before the 2023 spring bank stress episode.

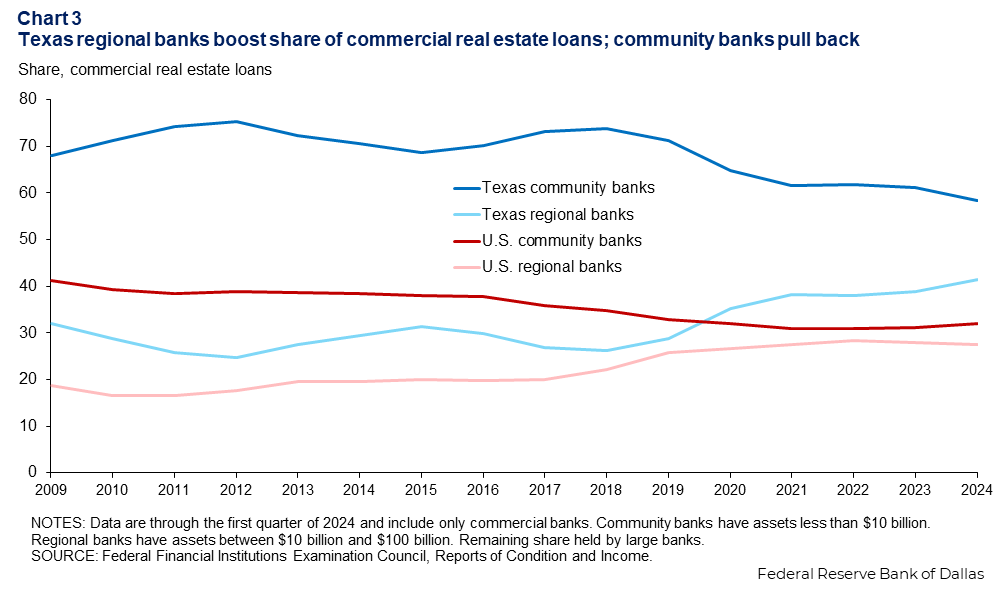

Texas community banks are disproportionately exposed to commercial real estate (CRE) loans, and some CRE categories are struggling, particularly offices and hotels. More than 58 percent of all CRE loans held by Texas banks are held by community banks compared with 42 percent by Texas regional banks (Chart 3).

The Texas community bank CRE share has dropped from a post-Global Financial Crisis peak of 77 percent in 2011. This decline became pronounced in 2018. Nationally, community banks only hold 32 percent of CRE loans and regional banks hold even less, 28 percent. The U.S. community bank share began its decline around 2015.

Put another way, CRE loans have an outsized presence in individual Texas community bank portfolios. In the first quarter of 2024, 55 percent of all Texas community bank loans were CRE loans compared with 42 percent for regional banks in the state. Nationally, 51 percent of community bank loans are in CRE compared with 42 percent for regional banks.

Some community bank leaders argue such characterizations ignore the type of CRE loans they hold. Their CRE loans are often essentially for owner-occupied structures—offices for professionals, such as doctors and dentists.

The heavy reliance on CRE in Texas means shocks can easily be transmitted. If the commercial real estate industry struggles, banks holding those loans will encounter difficulties and vice versa. Nationally, commercial real estate has hit a rough patch since the pandemic, when work-from-home arrangements pushed office vacancy rates higher and building valuations lower.

This has generated significant uncertainty about the health of CRE loans and, in turn, the health of community and regional banks, especially in Texas. The Texas ratio is one indicator to watch.

Texas ratio gained relevance during state banking collapse in the ’80s

During the turbulent 1980s when recessions and oil-price shocks wracked the state’s economy, hundreds of Texas banks failed. Texas banks had capitalized on high oil prices and aggressively lent to the energy sector in the 1970s. In addition, demand for office buildings increased as the energy sector grew, and Texas banks lent extensively to fund the structures.

As oil prices peaked and then collapsed by the mid-80s, Texas banks continued to aggressively make commercial real estate loans, leading to overbuilding. Office space demand dropped, and vacancy rates rose, ultimately leading to a bust in commercial real estate in 1986. During the ensuing banking crisis, more than 600 Texas banks failed or were acquired, including nine out of the 10 largest commercial banks in Texas. (San Antonio-based Frost Bank was the lone survivor.)

The Texas ratio was born out of these troubles. Intended to gauge how significant a bank’s troubled loans are, it is calculated by dividing a bank’s non-performing loans plus repossessed real estate by the sum of its tangible common equity and loan loss reserves. A ratio above 100 percent implies a bank’s capital cannot cover its potential asset losses.

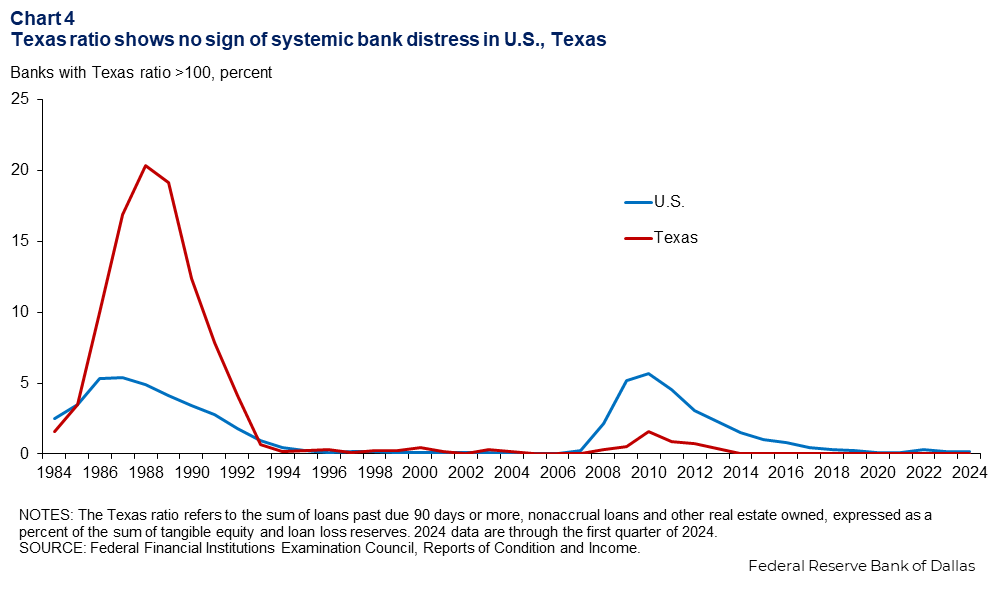

The Texas ratio peaked in the 1980s when slightly more than 20 percent of banks in the state exceeded 100 percent compared with 5 percent nationally (Chart 4).

The tables turned during the Global Financial Crisis, when the ratio exceeded 100 percent at almost six out of every 100 U.S. banks. The ratio in Texas didn’t exceed 2 percent.

More recently, no bank in Texas in 2023 and 2024 had a ratio exceeding 0, compared with a 0.2 percent share of institutions nationally during the two years. This is in line with previous routine fluctuations of the ratio and is not a sign of concern. Movement higher could indicate problems on the horizon for Texas and the nation.

Banks carry unrealized losses from fixed-income investments

Savings skyrocketed as the pandemic took hold in 2020. Bank deposits surged, a development the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis has chronicled. Businesses and households received significant pandemic-related financial assistance and savings built up, just as spending on services eased due to the pandemic lockdowns.

Unable to lend those deposits, banks instead acquired interest-bearing assets such as Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities. They were purchased when interest rates were low, meaning their value would decline when and if interest rates rose, which rates subsequently did in 2022 when the Federal Reserve began tightening monetary policy.

If these securities are held to maturity, the banks will get their invested principal plus interest. Should the banks require their invested funds before maturity, the securities would need to be sold at a loss, potentially eroding capital buffers.

Such losses led to the failure of Silicon Valley Bank, triggering concern nationwide about the liquidity and solvency of the banks after depositors became aware of the large amount of unrealized losses on bank balance sheets.

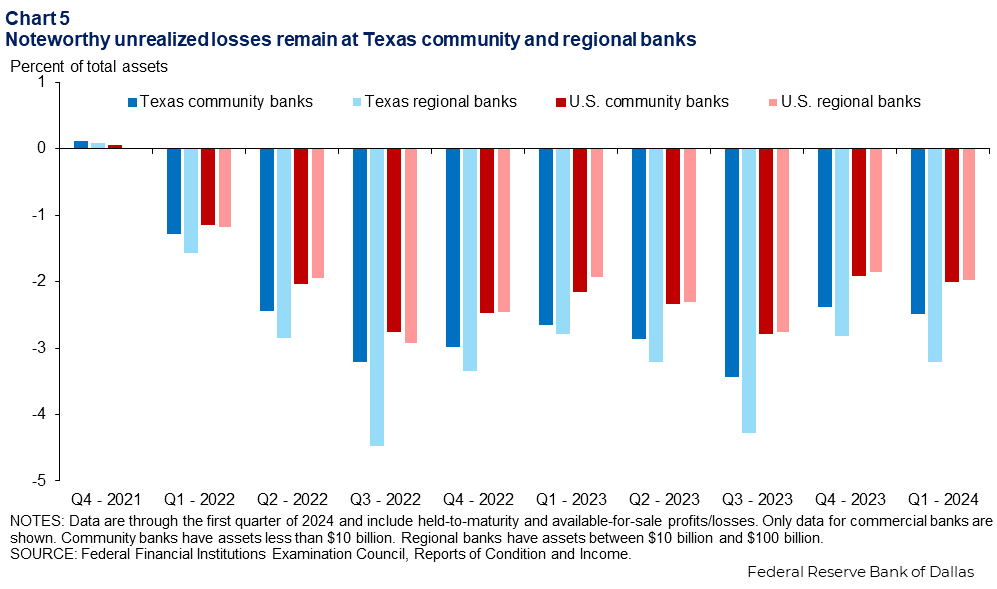

Both regional and community banks in Texas have carried more unrealized losses on securities as a percentage of total assets relative to their peers nationally since 2022 (Chart 5).

Unrealized losses have fluctuated quarterly. Unrealized losses peaked at 4.5 percent of assets in the third quarter of 2022 for Texas regional banks (falling to 3.2 percent in the first quarter of 2024) compared to 3.5 percent for Texas community banks in the third quarter of 2023 (falling to 2.5 percent in the first quarter of 2024). While the situation is anticipated to improve further as interest rates stabilize and more securities mature, the losses are worrying. Should the banks become compelled to sell the fixed-income securities at a loss, the banks’ ability to lend would be impeded.

For their part, banks have improved contingent liquidity planning since the March 2023 stress episodes. To reduce the risk of uninsured deposits and bank runs, banks have also increased the use of reciprocal deposits, exchanging pieces of large deposits among themselves so individual portions remain below the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.’s $250,000 insurance cap.

Liquidity access a leading banker concern

Access to liquidity is a top outlook concern for Texas banks, according to the Dallas Fed’s May Banking Conditions Survey, with 51 percent of respondents rating it a top three concern for the subsequent six months.

Banks are still competing for deposits, and there is uncertainty if deposits will increase in the remainder of 2024. If deposits don’t rise, banks will have to look elsewhere for funds. The Bank Term Funding Program, a Federal Reserve-sponsored source of liquidity created in the wake of the spring 2023 bank stress episode, expired in March 2024. Around 30 percent of the survey respondents said they used the program in 2023.

Additionally, potential changes to the lending practices of the federally backed Federal Home Loan Bank (FHLB) system could pose further challenges to banks. These changes could limit access for some banks to FHLB loans, which traditionally support mortgage lending and community investment. The March survey showed 75 percent of respondents expressed some degree of concern regarding potential changes to FHLB funding, with some 21 percent “extremely concerned.” No official rule change has been proposed.

The Federal Reserve is the lender of last resort, but the stigma and rules about using the discount window deter banks from relying on the facility for emergency funding unless under extreme duress.

Banks need funds to grow their loan portfolios. Competition for deposits and fewer sources of emergency funding will likely limit access to liquidity for banks and make it more costly to source funds. That could rein in loan growth.Bank capital absorbs losses

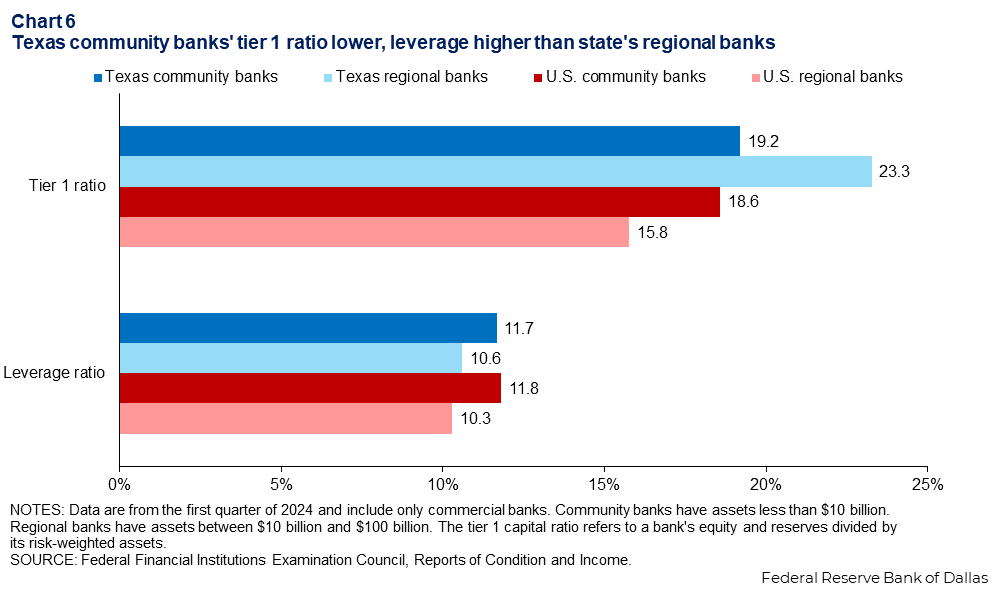

Banks can prepare for unexpected declines in asset values by holding on to capital. The most cited measure of a bank’s capital holdings is the tier 1 capital ratio: Equity and reserves divided by risk-weighted assets, with riskier assets carrying larger weights. (In banking parlance, a loan is an asset.)

The tier 1 capital ratio for Texas community banks (19.2 percent) is on par with U.S. community banks (18.6 percent) (Chart 6). This significantly exceeds the required minimum tier 1 capital ratio of 6 percent.

Texas regional banks’ ratio (23.3 percent) exceeds their U.S. regional peers (15.8 percent). This is because Texas regional banks have fewer risky assets, thus shrinking the risk-weighted denominator of the tier 1 ratio.

Looking at the leverage ratio, which does not utilize risk-weightings, the gap between Texas and U.S. regional banks closes almost entirely.

On average, community banks tend to hold more capital than regional ones do. There are several reasons for this, including small banks’ greater risk profiles because they lack diversification. Community banks also tend to be more risk averse than other types of banks, and they pursue an approach that’s the opposite of big banks’ too-big-to-fail mentality. Community banks know they will not be bailed out during times of trouble. Thus, the additional capital buffer will help them navigate future challenges.

In some cases, community banks use the community bank leverage ratio framework, which reduces capital requirements to a 9 percent tier 1 leverage ratio. (This still exceeds the 5 percent required in the general applicable rule.)

While Texas community banks persevered through a trying 2023, risks remain. Commercial real estate, unrealized losses and liquidity concerns persist and will not dissipate quickly.

About the authors