Inflation in services likely to rise further despite slowing goods prices

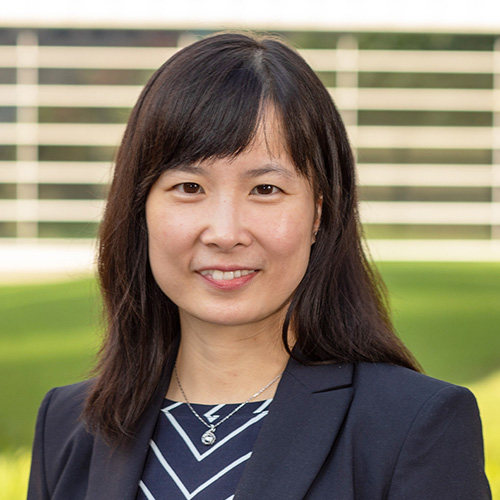

The core personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price index is a widely followed measure of inflation that excludes two of the most volatile price categories, food and energy. The 12-month core PCE inflation rate rose sharply from 1.5 percent in February 2021 to 5.3 percent in February 2022.

Since then, it has trended lower, slipping to 4.6 percent in July 2022. The recent decline has been almost entirely driven by moderating goods inflation (Chart 1). In contrast, services inflation has steadily risen overall during 2022.

Has services inflation peaked? Given rising demand for in-person services, the slow pass-through of surging house prices to rent and owners’ equivalent rent (OER), and higher health care worker wages, services inflation is likely to increase further. This implies that core PCE inflation—even if it has peaked due to declining goods inflation—is likely to fall slowly.

Services hit hardest by pandemic saw highest inflation

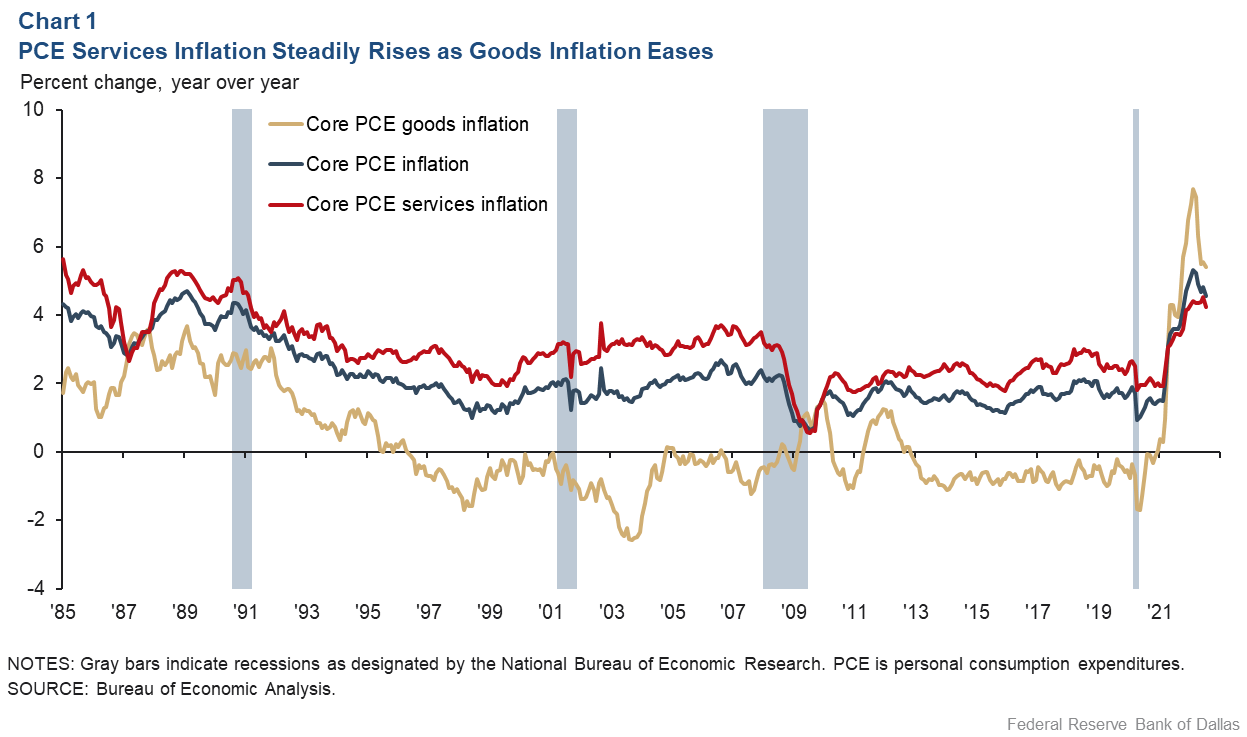

Chart 2 shows the contributions of four categories to 12-month core PCE services inflation. Transportation, recreation, accommodation and food services prices rose most in 2021. Inflation in this category averaged 3.4 percent in 2017–19 and declined during the pandemic’s early phase because of social distancing and reduced mobility, before increasing rapidly in 2021 and this year. By July 2022, it surged to more than 6 percent, contributing 1.3 percentage points (or 31 percent) to core PCE services inflation.

Real spending on these services has not returned to its trend level, suggesting that demand could increase further as the effects of the pandemic on consumer behavior fade. A tight labor market is likely to continue to put upward pressure on these sectors, which tend to be labor intensive.

Rent and owners’ equivalent rent inflation expected to increase further

Housing is another important driver of services inflation. During the first year of the pandemic, inflation attributable to rent and OER (the amount of rent equivalent to the cost of home ownership) declined. It began rising rapidly in the second half of 2021, and in the 12 months ended in July 2022, it rose to 5.9 percent (from 2 percent in May 2021).

Housing contributed 1.4 percentage points (or 32 percent) to core PCE services inflation in July. Rising rent and OER inflation reflect, with a lag, surging house prices since mid-2020.

The housing market has shown signs of cooling recently in response to higher mortgages rates. There are reasons to believe, however, that rent and OER inflation will continue to increase even if house-price growth has slowed.

Typically, renters adjust their leases infrequently, making the pass-through of surging house prices to rent costs a sluggish process. A recent Dallas Fed analysis suggests that rent and OER will add another 35 basis points to headline PCE inflation (and 40 basis points to core PCE inflation) in the coming months before easing in mid-2023.

Rising medical workers’ pay likely to push up PCE health care inflation

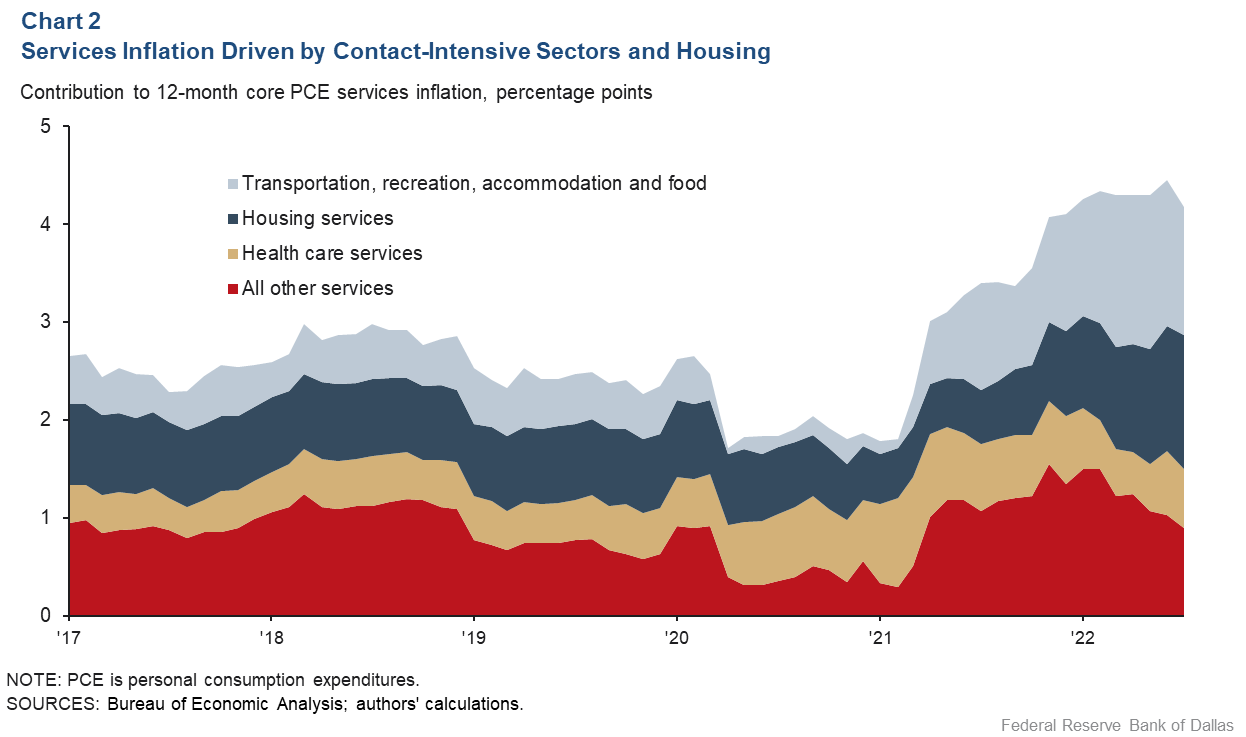

Another source of likely further upward pressure on PCE inflation is health care services. The weight of health care in the PCE price index is almost twice as large as in the Consumer Price Index, as a significant amount of health care spending is not paid by consumers out of pocket but by employers or government. Thus, health care inflation has a disproportionate impact on PCE inflation.

Health care inflation has been around 2 percent since 2022, close to its prepandemic level. This is likely to change, however, given the recent pace of rising wages for health care workers. Chart 3 shows that historically, wage growth among hospital workers has led PCE hospital services inflation and PCE health care inflation by about one year, which is also confirmed by computing the cross correlations between these series.

The strong correlation between the current wage growth among health care workers and future PCE health care inflation suggests that the health care component of the PCE price index is likely to add inflationary pressures in the coming year.

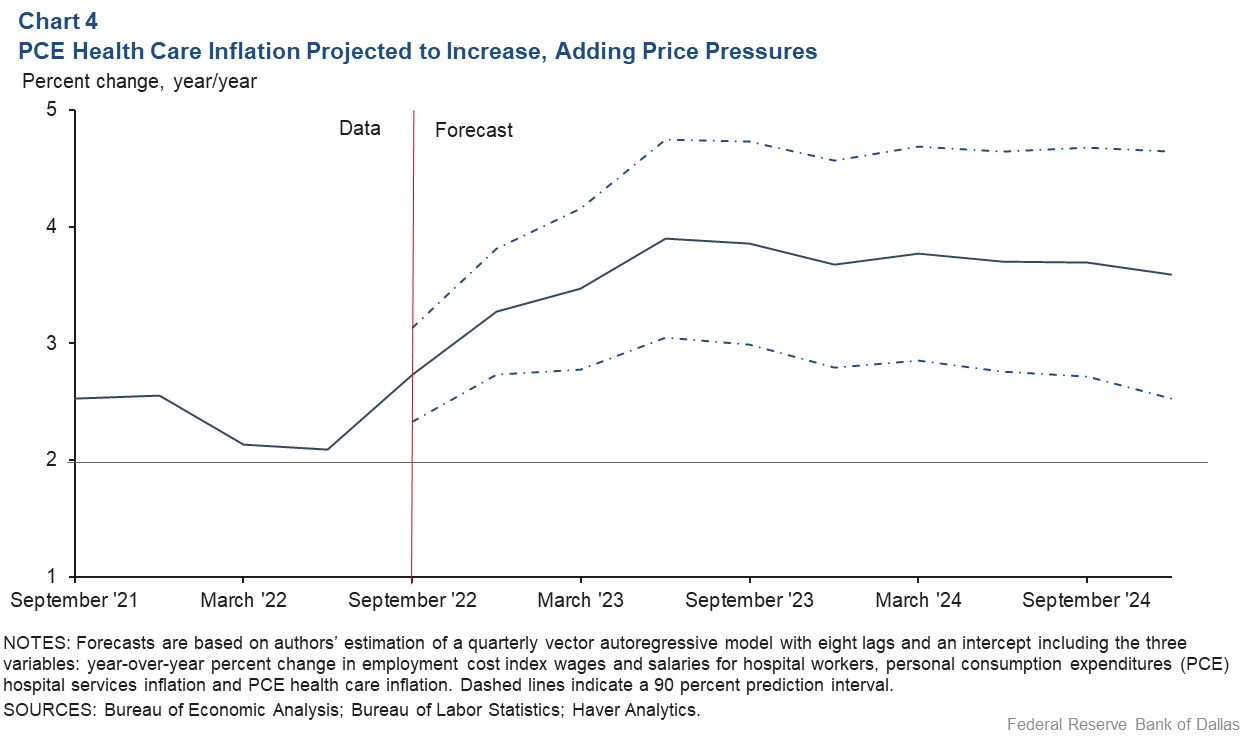

We estimate a vector autoregressive model (used to study the relationships of variables over time) including hospital workers’ wage growth, PCE hospital services inflation and PCE health care inflation. Based on the model, we project that PCE health care inflation will increase from 2.1 percent in second quarter 2022 to 3.9 percent in second quarter 2023 and will remain above 3.5 percent through 2024 (Chart 4).

Given the weight of health care in the core PCE price index (18 percent), our projection implies that health care will contribute 70 basis points to year-over-year core PCE inflation in the coming year, 32 basis points more than in second quarter 2022, all else equal.

Inflation pressures remain

Goods inflation, which drove the initial surge of overall inflation in 2021, has moderated in recent months and is likely to slow further. Forces behind this trend include declining consumer demand for goods, rising inventories at some retailers and improving supply chains.

Decelerating goods inflation, however, doesn’t guarantee a quick return to 2 percent overall inflation, as it is likely to be partially offset by firming services inflation. Rising demand for in-person services, the slow pass-through of surging house prices to rent and OER, and the lagged response of prices to fast-rising wages in sectors such as health care will likely support upward inflationary pressures, slowing the deceleration of PCE inflation.

About the Authors

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.