Skimming U.S. housing froth a delicate, daunting task

U.S. house prices appreciated a remarkable 94.5 percent from first quarter 2013 to second quarter 2022—a 60.8 percent rise after adjusting for inflation. The magnitude of the increase is even larger than that of the preceding housing boom, from first quarter 1998 to second quarter 2007.

House prices have risen especially rapidly since the pandemic began—from first quarter 2020 to second quarter 2022—accounting for roughly 40 percent of the decade-long appreciation. Measures of profitability (price to rent) and affordability (price to income) have also jumped in the past two years, past historic highs dating back to first quarter 1975.

This unprecedented pandemic boom poses an outsized risk for the U.S. economy, pressuring housing rents and, consequently inflation, higher. The possibility of a sharp price correction leading to an economic contraction—were one to materialize—would further complicate Federal Reserve inflation-fighting efforts.

Housing demand outstripped supply during pandemic

Fundamental forces—whether temporary or more persistent—spurred the initial house price surge. Robust disposable income supported by pandemic-related fiscal stimulus and cheap credit boosted consumer demand, while supply-chain disruptions, COVID-19-related lockdowns, and rising labor and raw construction materials costs pushed supply lower.

Pandemic-induced lifestyle changes—work-from-home arrangements and internal migration—also help explain why demand so outpaced housing supply early on.

A housing boom—such as the pandemic-era run-up—becomes frothy when the belief becomes widespread that today’s robust price increases will continue unabated. If many buyers and investors share this belief, purchases arising from a “fear of missing out” (FOMO) further drive up prices and reinforce expectations of strong (and accelerating) future gains beyond what fundamentals could justify.

This self-fulfilling mechanism leads to exponential price growth until a price correction inevitably occurs.

COVID-era boom became bubbly

Economists often disagree on the fundamental value of housing and what causes expectation-driven bubbles. There is greater agreement on how to identify unsustainable exponential growth—a symptom of a bubble—in the data.

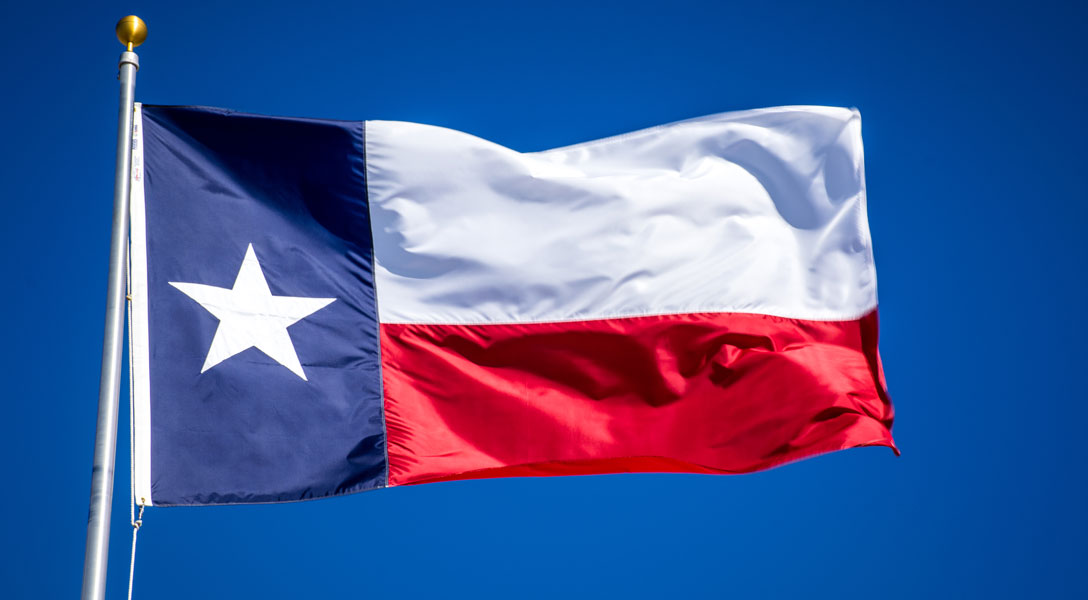

A novel empirical approach is based on so-called exuberance statistics. These measures can help detect if and when housing market indicators—quarterly real house prices, the house price-to-rent ratio and the house price-to-income ratio—start growing exponentially (Chart 1). An exuberance statistic above the 95 percent threshold signifies 95 percent confidence of abnormal unsustainable behavior in the underlying data series. Such episodes are identified in all charts with varying grades of shaded bars.

Prices adjusted for inflation rose 24.3 percent from first quarter 2020 to second quarter 2022, the largest nine-quarter gain since the mid–1970s and more than three times the rate of growth of the prior nine-quarter period (fourth quarter 2017 to first quarter 2020). This pace of acceleration cannot be easily reconciled with fundamentals, which did not display comparable behavior.

Moreover, the latest statistics from second quarter 2022 closely parallel the preceding housing bubble, with the data once again showing evidence of explosive behavior in the price-to-rent and price-to-income ratios as well. Accordingly, the pandemic surge before summer 2022 exhibited widening symptoms of a FOMO-driven bubble, one that extends beyond the U.S.

Monetary policy’s role easing housing booms

The relatively high number of new houses currently under construction can be a silver lining since supply catching up with demand can take some air out of the market and curb housing affordability woes. However, completions continue to lag. Recent data also show slowing housing sales and softening prices as borrowing costs surge, easing market pressure and, perhaps, enabling builders to chip away on order backlogs.

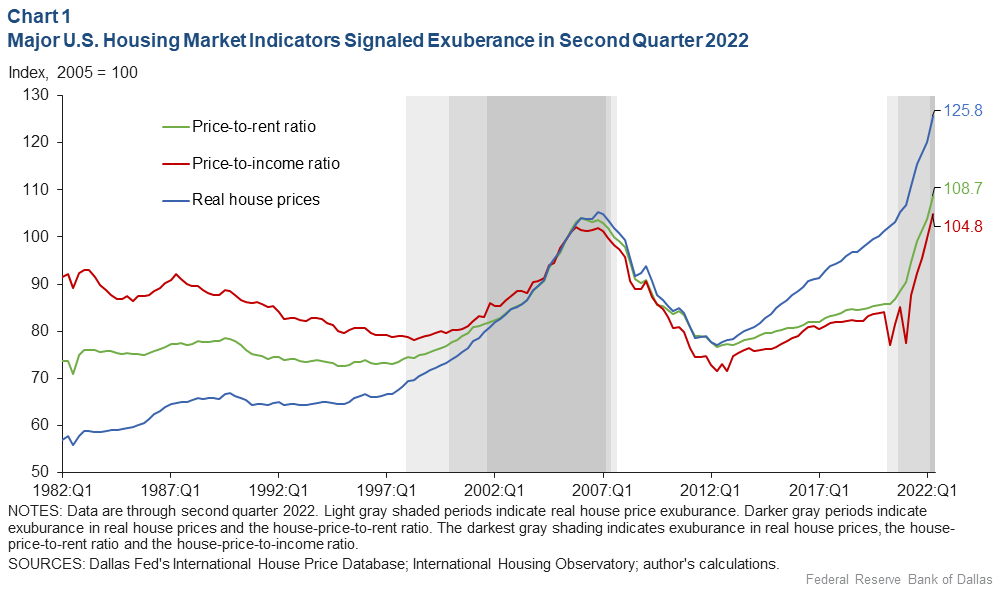

The share of mortgage debt service payments as a percent of personal disposable income stood at a historically low 3.9 percent in second quarter 2022. This remains well below the unsustainably high range of 6–7 percent reached at the peak of the last housing boom during 2005–07 (Chart 2). The mortgage share of income is poised to rise given the rapid increase of the 30-year mortgage rate―from 3 percent to above 6 percent at the end of third quarter 2022―induced by Fed monetary policy tightening since March 17, 2022. Rapidly rising mortgage rates have contributed to plummeting mortgage loan applications and declining housing sales.

The full effect of the ongoing tightening on households—including ultimately restraining housing demand—will take some time to be felt as the outstanding pool of mortgages gradually incorporates more of the recent vintages at higher rates.

Housing poses vulnerability for the U.S. economy

The red-hot pandemic-era housing market poses significant risks to the Fed’s dual mandate of price stability and maximum sustainable employment.

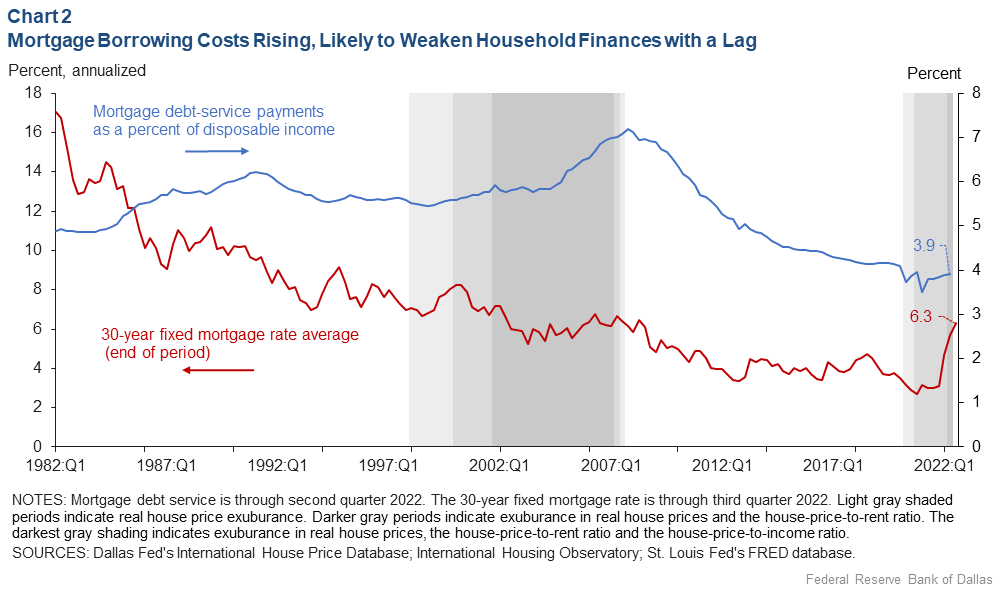

On the inflation side, the four-quarter change in asking rents climbed to 16 percent in second quarter 2022, modestly slowing to 12.2 percent in the third quarter, reflecting house price increases, according to Zillow data. The Bureau of Labor Statistics’ rent of shelter—a broad measure of household rental costs and a component of the Consumer Price Index (CPI)—reacts with a lag given that landlords’ asking rents are increased gradually as leases turn over. Even so, rent of shelter climbed to 6.2 percent in third quarter 2022—the sharpest rent increase since at least the early 1990s—and pushing overall CPI inflation higher (Chart 3).

Achieving a soft economic landing—taming inflation and avoiding a recession, as the Fed accomplished in 1994—cannot be taken for granted given that further monetary policy tightening can increase the household mortgage debt servicing burden and boost the odds of a severe house price correction.

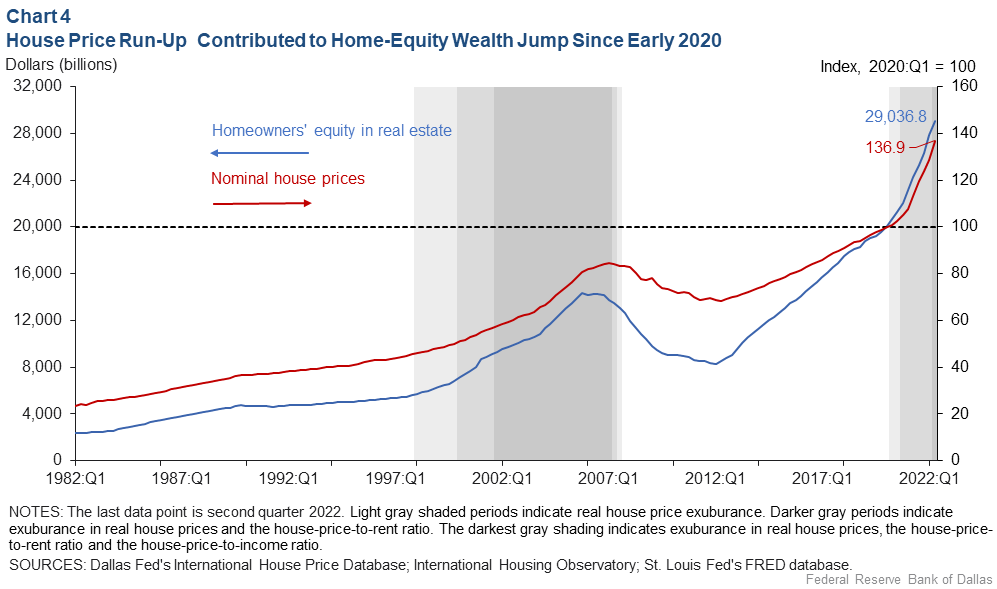

Housing wealth increased by nearly $9 trillion between first quarter 2020 and second quarter 2022, more than 82 percent through price gains rather than from an increase in the stock of housing (Chart 4).

Plausible estimates of the direct impact on housing wealth suggest that a pessimistic scenario—with a real price correction of 15–20 percent—could shave as much as 0.5–0.7 percentage points from real personal consumption expenditures. Such a negative wealth effect on aggregate demand would further restrain housing demand, deepening the price correction and setting in motion a negative feedback loop.

To complicate matters, the pandemic price boom has also widened wealth inequality since homeownership is the primary driver of household wealth.

Is a major housing correction unavoidable?

In the current environment, when housing demand is showing signs of softening, monetary policy needs to carefully thread the needle of bringing inflation down without setting off a downward house-price spiral—a significant housing sell-off—that could aggravate an economic downturn. Increasing mortgage rates, which follow from higher Fed policy rates, reduce the risk of prolonging the house price boom.

A gradual unwinding of the pandemic housing excesses can occur if policymakers can quell inflation without putting buyers under too much stress and can slow house price and rent increases while keeping underwater mortgages (housing worth less than what is owed) from rising.

Households and financial institutions are in better shape than during the housing boom and bust in the mid-2000s, likely providing more of a cushion to withstand some of the consequences of a negative wealth effect, were one to materialize.

However, after a housing boom partly driven by pandemic-era FOMO beliefs, cooling market participants’ expectations is key to shifting house prices toward a more sustainable path and avoiding the peril of a disorderly market correction.

A severe housing bust from the frothy pandemic run-up isn’t inevitable. Although the situation is challenging, there remains a window of opportunity to deflate the housing bubble while achieving the Fed’s preferred outcome of a soft landing. This is more likely to happen if the worst-case scenario of a price-correction-induced economic downturn can be avoided.

About the Author

Enrique Martínez-García

Martínez-García is a senior research economist and advisor in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.