Immigration crackdown likely contributing to weak Texas job growth

Texas’ strong domestic and international in-migration helps explain why state job growth outpaces that of the nation. In particular, international migration to Texas surged over the past three years, spurring strong state employment growth.

Those inflows have recently slowed. Findings from the Dallas Fed Texas Business Outlook Surveys (TBOS) suggest immigration policy changes will negatively affect the ability to hire and retain foreign-born workers at one in five Texas businesses this year. Among surveyed firms, 13 percent reported already experiencing a negative impact from policy changes.

Notably, TBOS likely understates the extent of such impact on Texas firms because the survey does not include some sectors that heavily rely on immigrant workers, such as construction and agriculture.

The extent to which immigration enforcement affects the labor market sheds light on the reasons behind weak employment growth this year regionally and nationally.

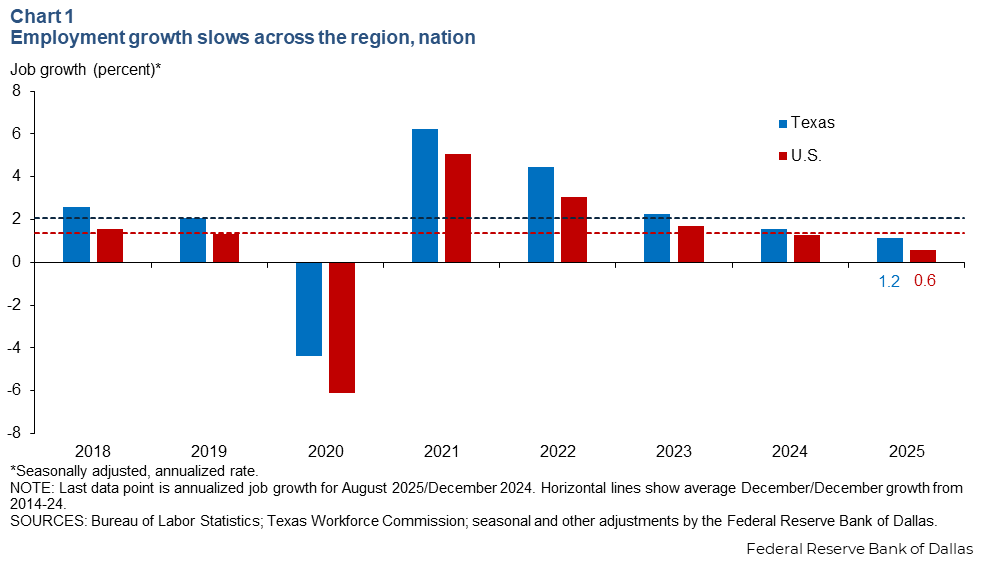

Although job growth has slowed steadily since the recovery from the pandemic recession in 2021, the growth rate has now dipped further below its long-run trend rate of about 2 percent in Texas (Chart 1).

Is subpar job creation the result of a fall in labor supply due to stricter immigration enforcement? Or is it attributable to waning labor demand brought on by other factors, such as higher tariffs and economic uncertainty? Results from the Dallas Fed TBOS special questions suggest immigration enforcement may play an important role curbing labor supply in the region, contributing to weak employment growth.

Impact of immigration policy changes began in mid-2024

Immigration enforcement can impact labor supply in a number of ways. First, increased enforcement along the Southwest border that began in mid-2024 sharply decreased the inflow of unauthorized immigrants. Legal immigration may also be slowing as processing times have increased. In addition, authorities have canceled the refugee resettlement program, intensified background checks, increased fees on visa applicants and imposed travel bans. These measures have affected legal inflows.

Second, temporary protective programs are ending, putting immigrants who had humanitarian protections into undocumented status and revoking their work permits. Between 2021 and 2024, at least 4 million immigrants were granted work permits as part of their humanitarian parole or asylum seeker status. Additionally, almost 1.3 million immigrants had temporary protected status, which includes work authorization, in early 2025. Many of those work permits and other humanitarian protections are being revoked.

Third, interior enforcement has increased, with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) arrests triple what they were at the end of the prior administration. The manner of arrests has also changed, with ICE officers apprehending migrants in places previously considered off-limits, including courts, schools and churches.

Arrests are not limited to immigrants suspected of being undocumented or criminals. They have included permanent residents and foreign students as well as migrants without criminal records.

The stepped-up visibility and intensity of enforcement has produced a chilling effect. As fear spreads in immigrant communities, foreign-born individuals are more likely to miss work or school and less likely to venture out to shops and restaurants. One retailer noted in the July TBOS, “[We have experienced] reduced sales to foreign-born customers, and customer counts [have been] down periodically due to raids by ICE in the area.”

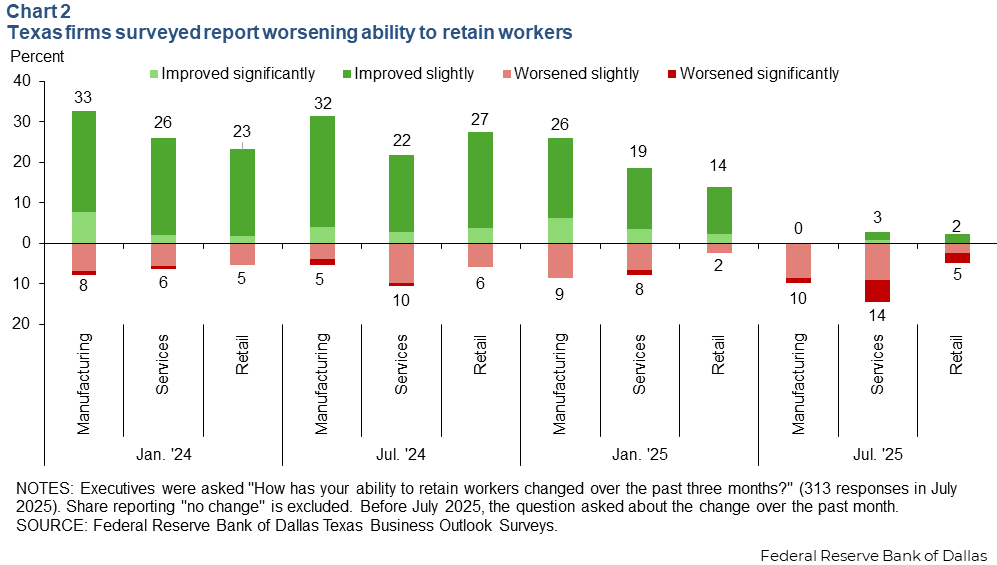

Retaining workers becomes more difficult

Texas firms’ overall ability to retain workers has declined on net in recent months. In a set of TBOS questions on labor market conditions in July, more firms reported a worsened ability to retain workers over the prior three months (13 percent) than an improved ability (2 percent), a sharp contrast to responses over the prior year and a half. The shifting sentiment is notable in the manufacturing, service and retail sectors (Chart 2).

More restrictive immigration policy is one factor hampering worker retention. Among survey respondents, 20 percent said immigration policy had hampered or is expected this year to hamper their ability to hire and retain foreign-born workers. The impact was more widespread in the service sector than in manufacturing, and it is more extensive among large firms.

This is not surprising since research shows that increased employee turnover (the rate at which workers are leaving their jobs) is a first-order impact of worksite immigration enforcement. Higher absenteeism is another impact. If workers are either losing their work permits or they fear commuting to work, absenteeism and turnover are likely to increase.

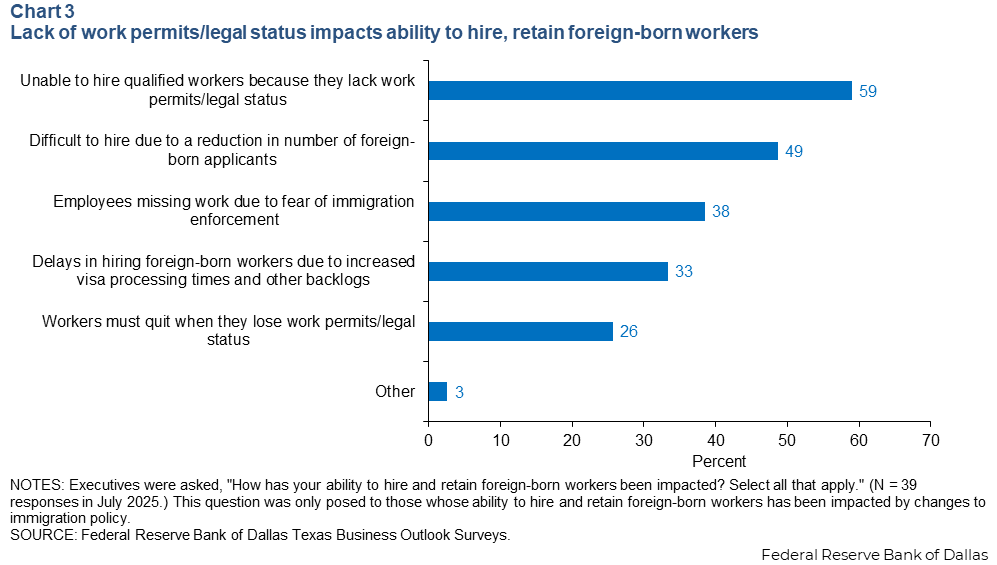

Among TBOS firms affected by immigration policy, about 40 percent indicated employees had missed work due to fear of immigration enforcement. A visitor’s bureau noted, “The hospitality community relies on considerable labor-intensive work—housekeeping, landscape, food and beverage, etc. Workers and contractors are more and more fearful of coming into work in hotels and restaurants.”

One real estate professional said, “Residents and contractors with legal status issues who have been working hard and minding their business for years are suddenly terrified. …They are quitting, hiding, avoiding activities and places they used to frequent and refusing to travel.”

More workers lacking legal status impedes hiring

Firms affected by immigration policy changes cite hiring difficulties as well as retention issues. Nearly 60 percent of impacted companies reported they were unable to hire qualified workers because such individuals often lack work permits or legal status (Chart 3). Additionally, 49 percent noted difficulty hiring due to fewer foreign-born applicants.

Will existing employees benefit?

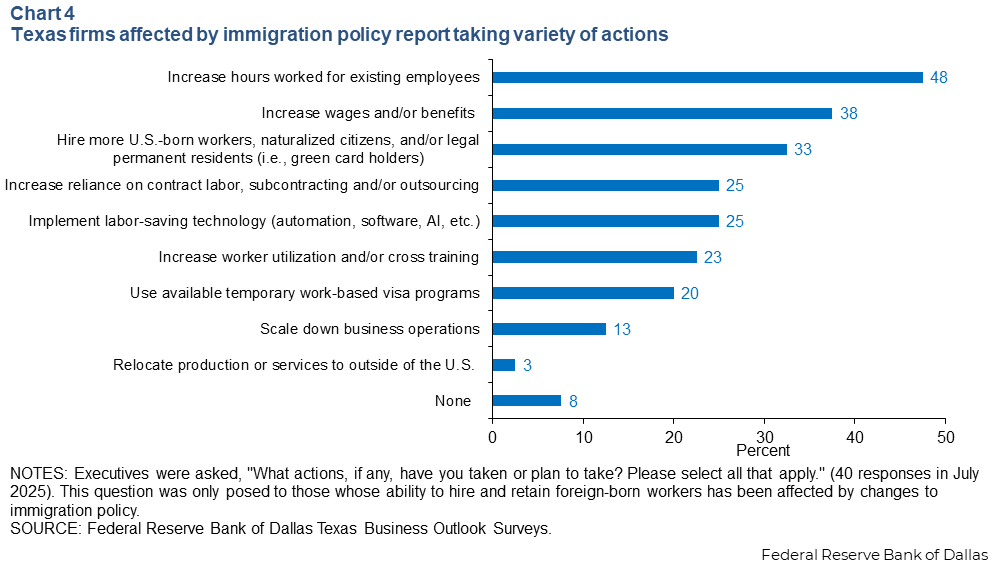

As recent immigrants become less able to work, whether due to loss of work permits or fear of deportation, Texas firms are taking measures to address the impact. Chief among them is increasing work hours for existing employees (Chart 4). Other responses are planned wage and benefit increases and more hiring of U.S.-born workers, naturalized citizens or legal permanent residents.

About 20 percent of affected firms said they would use available temporary work-based visa programs. That isn’t always easy, as one administrative and support services executive noted. “The temporary work-based visa programs are almost virtually impossible to navigate and are expensive,” the executive said. “There is no guarantee of success. We also fear that companies that have illegally hired in the past will now seek our employees. We fear they will push wages up.”

Most temporary work-based visa programs are limited by quotas and are oversubscribed, meaning many firms that apply for permission to hire foreign workers will not succeed in employing them. Often, similar U.S. workers are not readily available. If they were, companies would have likely sought them out in the first place, especially given the trouble and expense of legally hiring foreign workers.

One TBOS firm noted if companies could not secure workers with H-1B visas—the visa typically used to hire foreign professionals in fields such as technology and medicine—then the result may very well be outsourcing and offshoring.

One-quarter of impacted TBOS firms cited hiring contract labor, subcontractors or outsourcing as a consequence of an inability to hire or retain foreign workers. An additional 3 percent noted relocating production or services to outside the U.S. As one company official in the professional and businesses services sector said, “About 8 to 10 percent of our workforce is H-1B. We are seeing that the unpredictable nature of the process, unpredictable rejections and revoking, etc. has led to a lack of mobility in the workforce. We are also seeing that many companies don't want to deal with it and are turning more and more to outsourcing to nearshore and offshore. This results in the job being sent abroad, and most likely this job will never come back to the U.S.”

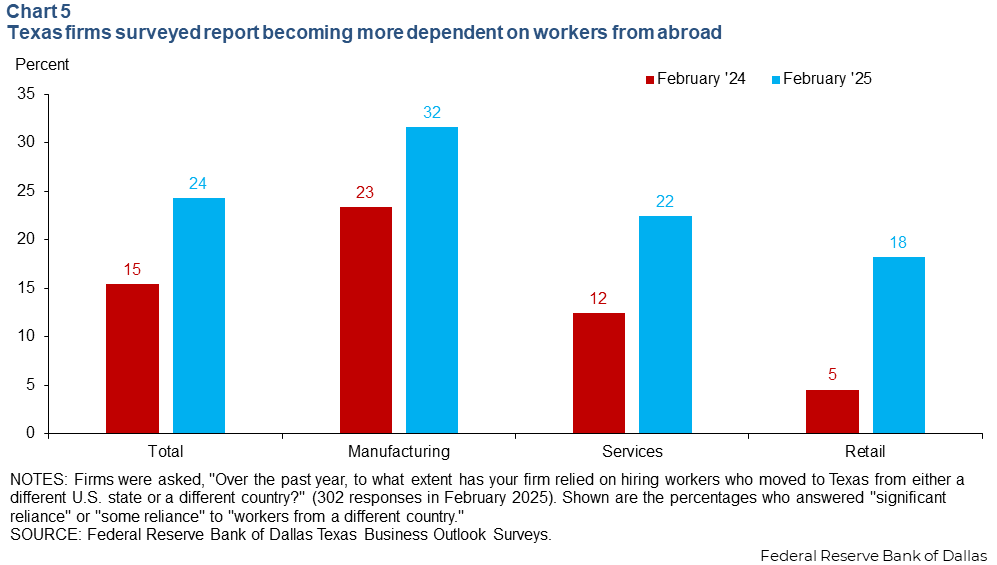

Texas businesses increasingly rely on workers from other countries

Changes to immigration policy have come at a time when Texas businesses have become more dependent on immigrant workers, due in part to the 2021–24 immigration surge. By some estimates, Texas got at least 10 percent of that border immigration surge—at least 550,000 extra immigrants—so it’s no surprise that firms grew more dependent on foreign-born workers. The February TBOS indicated that roughly a quarter of responding Texas businesses relied on workers from outside the country in 2024 (Chart 5). This was a large increase from 15 percent just one year prior.

Notably, during the immigration surge, humanitarian immigrants coming across the border were eligible for work permits and thus could legally work. Firms could legally hire them, which they did.

Labor market outlook weaker without immigration

Since the immigration enforcement changes began in mid-2024, U.S. and Texas job growth have fallen well below their respective long-run trends. Given the decline in immigration inflows, increase in arrests and removals of immigrants already here and the chilling effect, labor supply is clearly being affected.

In the country as a whole, the labor force contracted and the participation rate declined from recent peaks earlier this year, in April. In Texas, labor force growth is at very low levels. Meanwhile, signs of weakening labor demand are harder to spot, particularly in Texas. The state unemployment rate is low, at 4.1 percent, job postings are holding steady, and wage growth remains healthy.

With sharply lower immigration, break-even job growth shifts downward. Break-even job growth is the pace of job creation consistent with a stable unemployment rate. If job growth is below (above) the break-even rate, then the unemployment rate will rise (fall). When the immigration surge was at its peak, economists estimated that U.S. break-even job growth was around 250,000 jobs per month, a huge jump from the long-run break-even employment growth rate, estimated at 70,000 to 90,000 net new jobs per month. Current estimates of break-even employment growth are approaching 30,000 jobs. This compares with average U.S. job creation this year through August of roughly 75,000 jobs per month.

Less immigration doesn’t necessarily mean higher or lower unemployment, but it will likely result in slower economic growth. The labor market will show this first in the form of less job growth. Lower GDP growth will eventually follow. The U.S.-born workforce cannot make up for reduced immigration due to demographic pressures, including an aging population and low birth rates.

Some—but likely not all—of the decline in labor supply will be offset with mechanization, technological innovation (including artificial intelligence) or offshoring. Nevertheless, it bears noting that by 2031, all growth in the U.S. population is expected to come from immigration. Hence, when officials set immigration policy, they may also be setting the speed limit for the economy.

About the authors