Payment system design can encourage intraday liquidity efficiency

Bank reserves, because of their intraday liquidity, are an unusual asset. They support the settlement of payments and help banks manage short-term requirements throughout the day.

Estimates of bank demand for reserves have increased meaningfully since the Global Financial Crisis (2007–08), driven by regulatory constraints, changing preferences in bank use of Federal Reserve Bank daylight overdrafts and frictions in the redistribution of reserves via short-term funding markets.

Officials have cited the benefits of achieving an efficient central bank balance sheet, drawing attention to potential actions that could aid the process. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Open Markets Desk recently implemented one such measure, the provision of central bank liquidity earlier in the day.

While academics and policymakers have discussed many measures, one has received comparatively less attention: payment system design features that can promote liquidity efficiency.

Reserves play a fundamental role in intraday liquidity management

Reserves are crucial for intraday liquidity management because they are immediately available and do not require monetization, unlike other highly liquid assets such as Treasuries. Multiple factors, including regulatory requirements and payment needs, drive bank demand for reserves, and thus, aggregate reserve demand across the banking system.

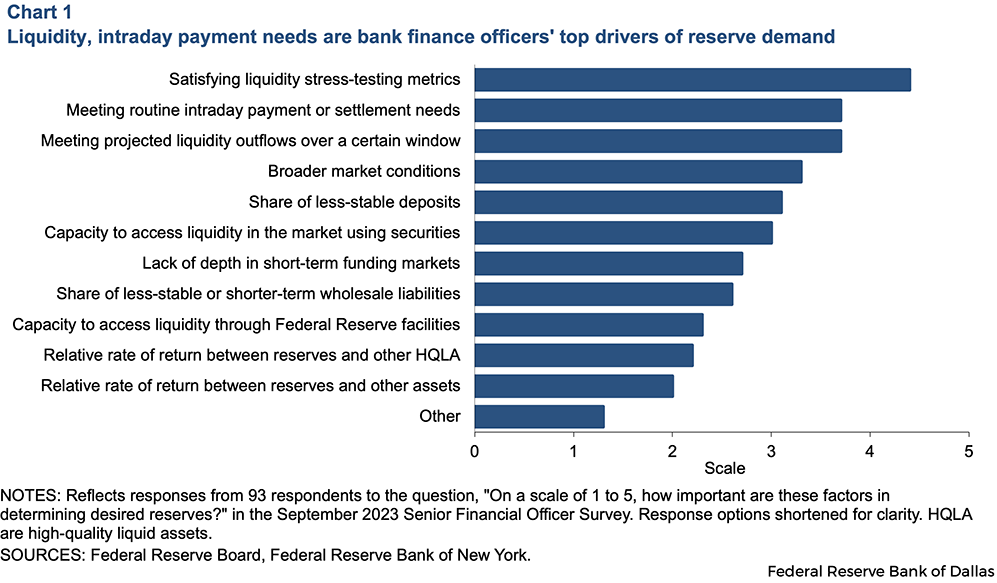

The Federal Reserve’s September 2023 Senior Financial Officer Survey reported that satisfying liquidity stress-testing metrics, meeting projected outflows and meeting routine intraday payment or settlement needs were the most important determinants of an institution’s desired level of reserves (Chart 1).

Although these factors are presented separately here, they are intertwined. Under liquidity regulations, banks are incentivized to hold enough reserves to meet payment needs and expected outflows without incurring daylight overdrafts.

Aggregate reserves and payments volumes change over time

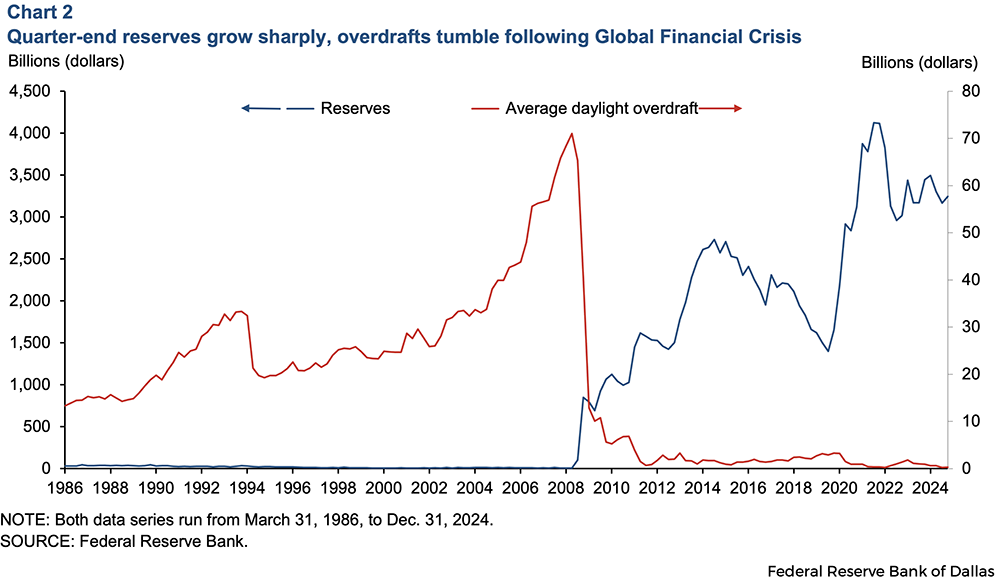

Before the Global Financial Crisis, the aggregate supply of reserve balances was comparatively small, less than $50 billion. Daily payment volumes were also lower, but the growth in reserves in the intervening years has far outstripped the growth in payments.

In 2005, the average daily value of payments made through the Fedwire Funds Service (the Fed’s large-value payment system) was around $2 trillion. By 2024, the average daily payments value rose to roughly $4.5 trillion. Over this same period, reserves grew to an average of $3.2 trillion from just $12 billion. The significantly lower level of reserves pre-crisis was sufficient for banks to manage intraday payment needs and for funding markets to function efficiently, in part because banks made liberal use of daylight overdrafts.

Daylight overdraft usage declines

Following the financial crisis, as reserves grew sharply amid Fed asset purchases, daylight overdraft usage declined to near zero (Chart 2). Banks were then remunerated for their reserves, removing an incentive to economize in favor of assets with a higher return.

Banks’ significantly larger holdings meant they were able to meet payment needs without turning to daylight overdraft. Some institutions also began to view daylight overdraft usage as undesirable, not unlike perceived discount window stigma.

Liquidity regulations change

Importantly, there were also significant changes in bank liquidity and capital regulations. In the United States and other advanced economies, large banks must hold enough high-quality liquid assets to cover their projected net outflows in a stress event lasting 30 days under the Fed’s liquidity coverage ratio calculation.

Although Treasury securities and reserves are both classified as the highest level of high-quality liquid assets, banks may have concerns about their ability to fully monetize their Treasury holdings in times of acute stress. Some banks have also previously reported they believe their regulators would prefer them to hold a greater share of their high-quality liquid assets as reserves.

Large banks must also conduct internal liquidity stress tests that assess their ability to meet outflows over a variety of time horizons, including overnight. Daylight overdraft borrowing risks possibly converting an intraday credit extension to overnight borrowing, via the discount window, if expected payments are not received later in the day. This would adversely affect a firm’s liquidity projections and could force it to hold a higher level of reserves.

Additionally, the largest U.S. banks are required to submit resolution plans, also known as “living wills,” to regulators. These plans describe how a bank would wind down in an orderly way should it fail. Historically, banks’ wills have not relied on incurring daylight overdrafts or borrowing from the discount window for more than a few days. Banks have also asked regulators for greater clarity about the extent to which they can assume discount window access in a resolution scenario.

Frictions in reserves redistribution affect funding costs

Funding costs, particularly in the repurchase agreement (repo) market, can reflect a decline in aggregate reserves toward scarce levels and frictions in redistribution of reserves among banks. The Office of Financial Research suggested internal frictions at banks, likely driven by liquidity requirements, may have contributed to banks’ reluctance to lend excess reserves into the market in response to an unusually sharp increase in repo rates in September 2019.

While regulatory liquidity constraints directly apply to depository institutions, their effect is felt among non-bank market participants who use bank services. Non-bank financial institutions, including broker-dealers and hedge funds, are major participants in Treasury and repo markets.

These entities settle their transactions through accounts at custodian banks, which will charge daylight overdraft fees if clearing accounts are not fully funded by 8:30 a.m. ET. Repo participants, particularly small broker-dealers who rely on interdealer repo markets for funding, are incentivized to fund their accounts before the start of daylight overdraft calculations.

This is a significant reason for the concentration of repo market activity in the first 90 minutes of trading each day. These financial market participants also face other intraday liquidity needs, including posting margin to financial market utilities due to changes in the value of open trading positions or their underlying collateral, such as futures and derivatives.

Liquidity affects monetary policy implementation

Short-term rates can trade outside the Federal Reserve’s target range because of inefficiencies and frictions in reserve distribution, affecting the duration of the Fed’s ongoing balance sheet reduction. If banks were less inclined to maintain excess reserves above their minimum needs, the Fed could operate with a smaller balance sheet in the long run.

There are a variety of options that could make banks more comfortable with a lower level of reserves, including changes to liquidity guidance, greater usage of Federal Reserve facilities or tweaks to the structure of the payments system.

Features of many large-value payment systems globally are specifically designed to counteract bank liquidity hoarding. Throughput targets, or throughput rules, require payment system participants to make a certain fraction of their outgoing payments by specific times each day.

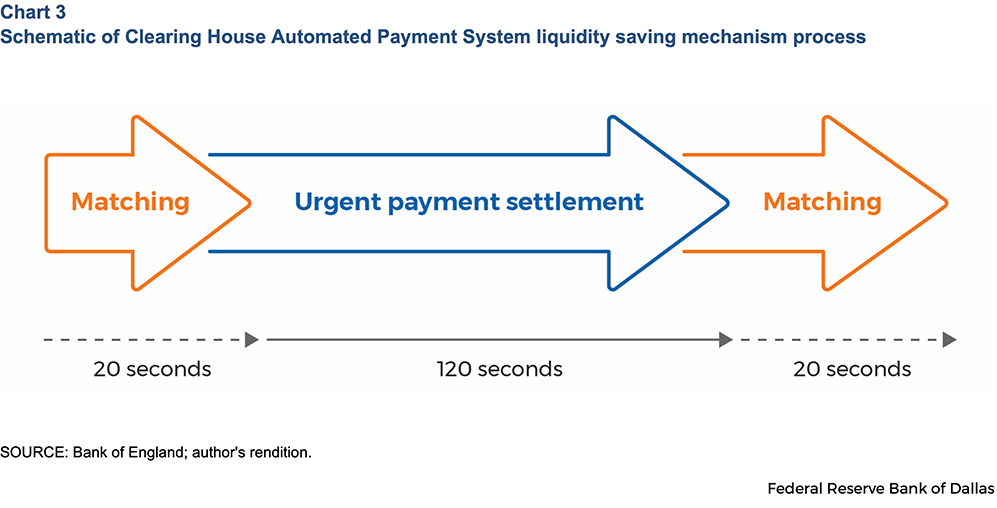

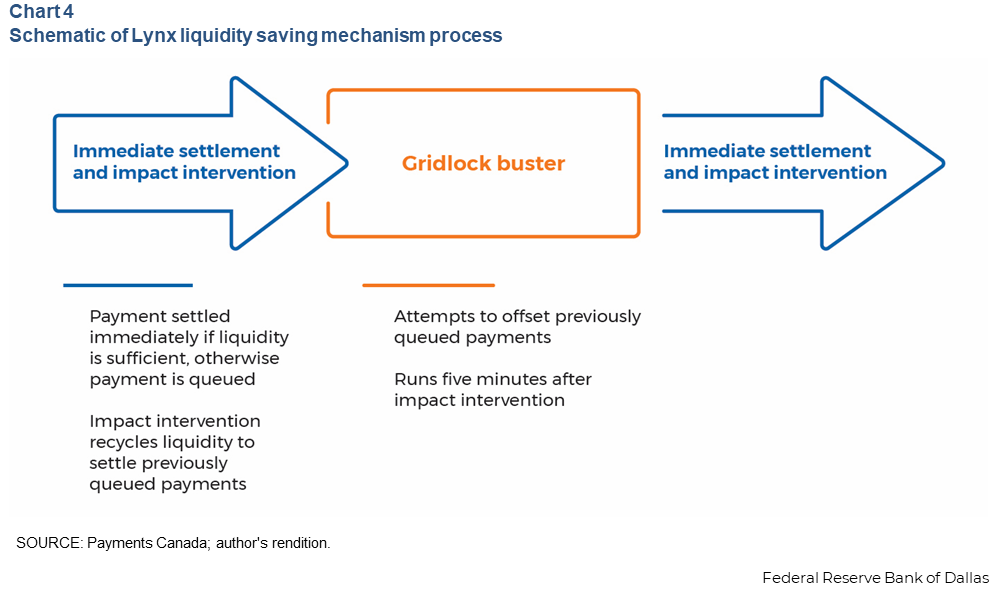

In the U.K., the Clearing House Automated Payment System (CHAPS) uses throughput targets and a liquidity saving mechanism that simultaneously settles certain offsetting payments to influence participant behavior. Canada’s Lynx system also incorporates throughput targets and a liquidity saving mechanism, in addition to two other mechanisms participants can use to maximize the efficiency of their payments and intraday liquidity management. By contrast, the Fedwire Funds Service uses neither throughput targets nor a liquidity saving mechanism (Table 1).

Table 1: Summary statistics of U.K., Canada, U.S. large value payment systems

| Jurisdiction | United Kingdom | Canada | United States |

| Large value payment system | CHAPS | Lynx | Fedwire Funds |

| Average daily volume of payments | 212,047 | 53,778 | 912,515 |

| Average daily value of payments | £378 billion ($510 billion) | C$341 billion ($247 billion) | $4.8 trillion |

| Average level of reserves | £688 billion | C$87 billion | $3.3 trillion |

| Throughput rules | Yes, on payment value | Yes, on payment value and volume | No |

| Liquidity saving mechanism | Yes | Yes | No |

| Other mechanisms | No | Yes | No |

| Hours of operation | 6 a.m.—6 p.m. GMT/London Time | 12:30 a.m.—7 p.m. ET | 9 p.m. ET—7 p.m. ET |

NOTES: U.K. statistics as of second quarter 2025; Canada and U.S. statistics as of June 2025. Throughput rules implement intraday deadlines for a certain share of volume or value of total payments. Liquidity saving mechanisms identify offsetting payments and settle them simultaneously. Other mechanisms include urgent payments and payments to the central bank, among other options. U.K. hours of operation are indicated to show both summer and remainder-of-the year periods.

Throughput targets encourage efficiencies

Central banks in the U.K. and Canada maintain throughput rules to ensure a certain fraction of outgoing payments by specific times each day. The Bank of England groups participants into three categories based on the value of their gross payments or their systemic importance. Category A and B participants must make 50 percent (by value) of their outgoing payments by noon, 75 percent by 3 p.m. and 90 percent by 5 p.m.

In Canada, throughput targets are applied to both the volume and value of payment messages. Payments Canada, the operator of Lynx, requires all participants ensure 40 percent of volume (dollar value of 25 percent) is settled by 10 a.m., 60 percent of volume (dollar value of 60 percent) by 1 p.m. and 80 percent of volume (dollar value of 80 percent) percent by 4:30 p.m. Throughput targets are intended to allow participants to manage their liquidity in a predictable manner, improving systemwide efficiency.

In the absence of such targets, participants are incentivized to withhold outgoing payments to avoid experiencing liquidity shortages. Previous research shows that banks settle more than half of their Fedwire transactions in the last third of the day, often between 3 p.m. and 4:30 p.m., indicative of institutions managing their intraday liquidity by delaying outgoing funds. This research also showed that intraday timing of Fedwire payments is responsive to the level of aggregate reserves in the system.

Liquidity saving mechanisms create efficiencies

CHAPS, Lynx and Fedwire are examples of real-time gross settlement payment systems. A 2020 World Bank survey reported that 96 percent of 120 respondent jurisdictions are using at least one such payment system. Although these systems require large amounts of liquidity to support gross settlement, they provide benefits by reducing systemic risk.

By comparison, in a net settlement system, which aggregates payments and settles them as a single net amount, participants may be concerned about the possibility of individual payment failure, which could have significant knock-on effects. In an attempt to reduce liquidity needs while preserving the real-time gross settlement structure, CHAPS and Lynx and their counterparts globally introduced liquidity saving mechanisms.

The mechanisms allows payment system participants to gain some of the benefits of net settlement while maintaining the gross settlement structure. Although the liquidity savings mechanisms differ slightly across real-time gross settlement systems, they generally work by identifying offsetting payments and settling them simultaneously.

In the U.K., the liquidity savings mechanism takes the form of repeated cycles of roughly 140 seconds in which non-urgent payments are queued and then settled concurrently. Queued payments can be controlled via the central scheduler, which also offers other liquidity management tools, including the ability to limit the amount of funds available for a particular matching cycle or change a non-urgent payment’s priority to urgent.

During the two-minute period in Chart 3, only urgent payments are settled while non-urgent payments are queued, awaiting settlement during the next matching cycle. During this 20 second cycle, an algorithm attempts to find offsetting payments that can be settled simultaneously.

This process is repeated throughout the day. Following the mechanism’s introduction in 2013, the Bank of England estimated the mechanism resulted in a 20 percent reduction in intraday liquidity costs among clearing participants.

In Canada, participants can also opt to send their payments to a liquidity saving mechanism. If sufficient liquidity is not immediately available, the payment is queued. The liquidity saving mechanism uses impact intervention, which is triggered when a Lynx participant’s payments queue or available liquidity changes (Chart 4).

During impact intervention, the system attempts to settle queued payments using first-in-first-out bypass, allowing settlement of smaller payments before larger ones, even if they were submitted later. Like CHAPS, Lynx also features an offsetting algorithm, known as the gridlock buster, which runs five minutes after an impact intervention occurs.

The algorithm identifies offsetting queued payments on either a multilateral or bilateral basis. Unlike CHAPS, Lynx offers four levels of payment prioritization, although a distinct urgent payment mechanism is also available, separate from the liquidity-saving mechanism.

Although Fedwire has not incorporated throughput rules or a liquidity-saving mechanism, it implemented changes aimed at shaping liquidity management behavior. Before 2008, participants were charged a fee of 36 basis points for all intraday credit usage. Subsequently, the fee for collateralized daylight overdrafts was lowered to zero to reduce incentives to queue payments, while the fee for uncollateralized overdrafts increased to 50 basis points.

What future developments could alter intraday liquidity demands?

It is unlikely that the fundamental drivers of intraday liquidity demand will change materially in the foreseeable future. However, developments in financial market structure could alter banks’ intraday liquidity management strategies.

Should wider adoption of stablecoins occur, it could change the volume of payments conducted via large value payment systems or bank demand for reserves. Various market participants are actively exploring intraday repo, which may increase institutions’ willingness to lend excess reserves for short periods of time, improving liquidity efficiency.

The official sector could also change liquidity regulations or guidance, which could reduce the minimum level of reserves banks feel necessary to maintain. Payments systems improvements could offer another alternative.

About the authors