China expands Mexico investment but notably lags U.S., other G7 economies

China has been the fastest growing source of foreign direct investment (FDI) to Mexico in recent years. Chinese investment has also become a prominent issue in U.S.-Mexico economic relations.

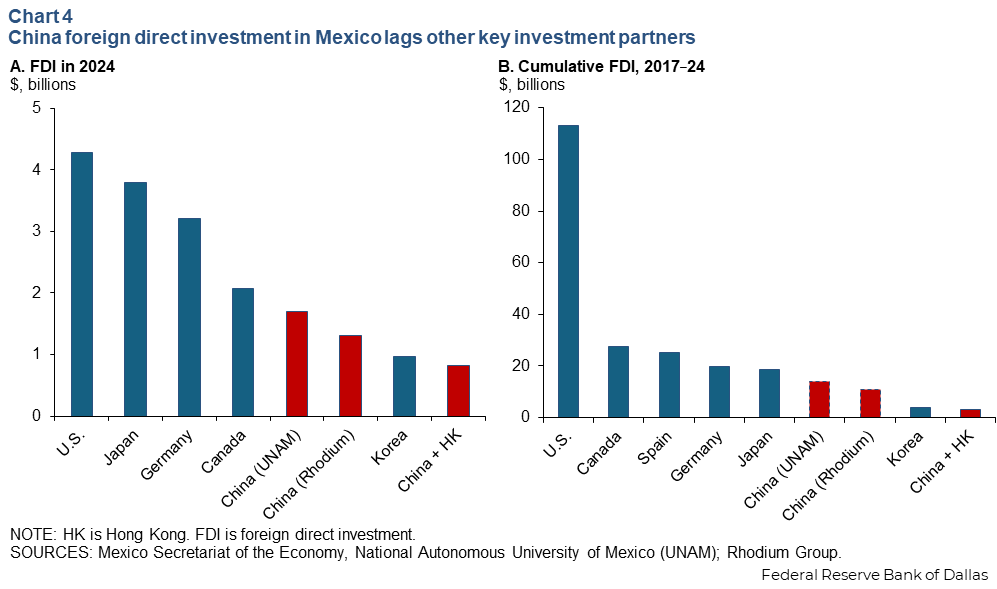

However, this FDI remains small compared with U.S. investment in Mexico. China also significantly trails investment from Canada, Spain, Germany and Japan, in data from official sources or from larger academic or private sector estimates. These figures underscore that the U.S. and other advanced economies have driven nearshoring investment in Mexico.

Nevertheless, Chinese firms in Mexico have played a large and visible role in new (greenfield) investment. Given China’s dominant role in global manufacturing, its investments could be essential to deepen the nearshoring of supply chains.

China’s role as global investor evolves

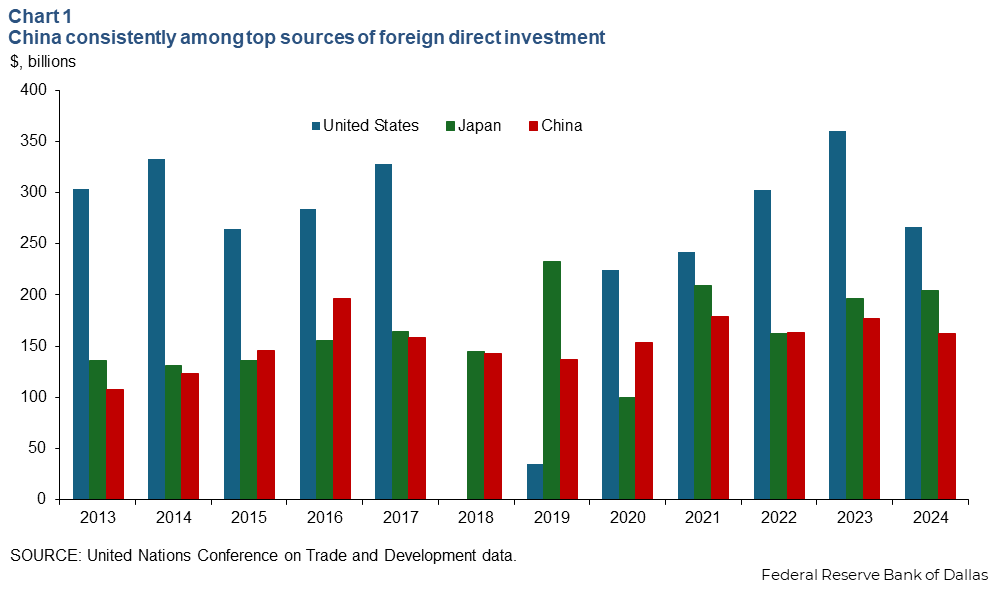

China has emerged during the past two decades as one of the world’s top three sources of FDI after the U.S. and Japan (Chart 1).

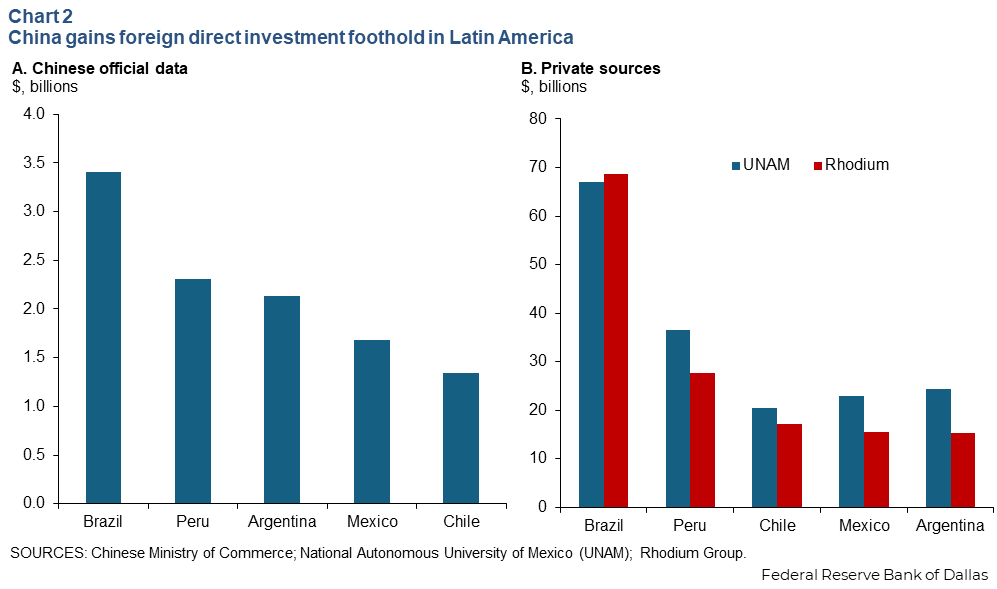

Acquisitions, particularly in developed markets as well as large infrastructure projects, drove the first wave of Chinese outbound direct investment, peaking in 2016–17. These large infrastructure projects have been associated with China’s Belt and Road Initiative, which came to Latin America relatively late. Large Belt and Road investments included railways, ports and mining projects in Argentina, Chile and Peru. Brazil has been by far the largest recipient of Chinese FDI in the region (Chart 2). However, Brazil and Mexico have avoided Belt and Road participation.

After bottoming in 2019–20, China’s global outbound direct investment has rebounded, driven by private companies’ greenfield investments and a shift toward emerging markets. An increasing share of investment has been in overseas manufacturing, particularly in Southeast Asia. The shift partly reflects a response to tariffs on China’s exports and increasing labor costs in China. It is also indicative of Chinese suppliers following their multinational firm customers, who have sought to diversify their supply chains.

Chinese investment in Mexico has largely been part of this second, recent wave.

Measuring Chinese FDI in Mexico challenging

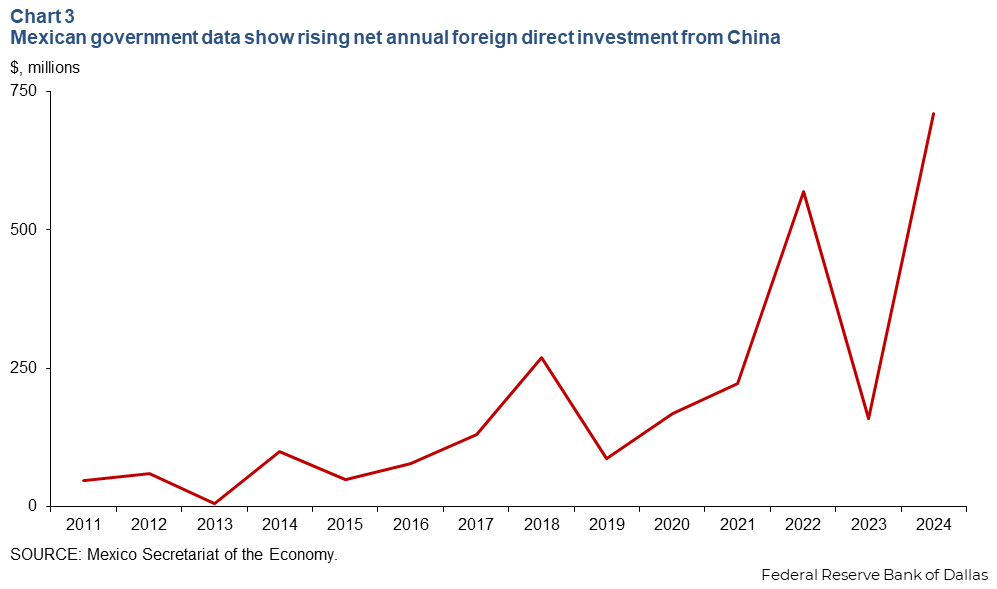

Net FDI flows from China have grown rapidly over the past decade, according to data from Mexico’s Secretariat of the Economy. China’s FDI increased incrementally in 2014–15, then accelerated following the 2018–19 U.S.–China trade war and the U.S. –Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA) taking effect in mid-2020 (Chart 3).

Cumulatively, Mexico received $2.3 billion in net FDI from China from 2017–24, according to official Mexican statistics. The net amount rises to $3.2 billion when including Hong Kong, a special administrative region of China. The larger figure accounts for 1.2 percent of FDI into Mexico during the period, compared with $113 billion from the United States, amounting to 40 percent of total FDI.

Private sources that track individual company announcements and disclosures estimate Chinese FDI in Mexico to be several times larger than official figures show. The private sources are focused on FDI inflows, rather than net FDI (inflows minus disinvestments). They also calculate Chinese investment by nationality (Chinese-owned companies), rather than on a residence basis (where the investment is coming from, the international standard in balance-of-payments statistics). Thus, the private sources are not immediately comparable with the official data, which follow the international standard. However, the private data may provide a fuller sense of the presence of Chinese firms in Mexico.

The Center for Chinese-Mexican Studies at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, which monitors Chinese investments across Latin America, estimates that FDI inflows from China into Mexico exceeded $2 billion in each of the past three years (totaling $14 billion since 2017). Rhodium Group, a U.S.-based research firm that monitors China economic trends, similarly estimates $2.5 billion in FDI from Chinese companies into Mexico in 2024, and cumulative FDI inflows of $11.5 billion since 2017.

The way the investment is reported is a key reason these alternate estimates are considerably larger. Much of Chinese companies’ investment worldwide comes from offshore affiliates, and, thus, does not show up in official data as originating in China.

China maintains relatively strict capital controls and tightened regulatory scrutiny of outbound investments after it experienced balance of payments stress in 2016. Chinese companies are thus incentivized to keep or raise funds offshore for their investments. This investment shows up in official data as non-Chinese FDI, presenting a challenge across jurisdictions when assessing the full scale of Chinese companies’ activities.

Firm-level data may overstate Chinese activity in some cases, including when FDI transactions do not materialize at the levels announced. More broadly, the impact of FDI commitments on national accounts is lagged and may well show up in future data releases.

The Baker Institute at Rice University reviewed the data and Mexico’s 500 industrial parks, identifying 200 discrete investments with ultimate beneficial owners from China. The Baker Institute estimated a total stock of Chinese FDI in Mexico of $15 billion, much larger than the official data show, but also substantially lower than the National Autonomous University’s estimate of $22.5 billion.

Based on the higher private estimates, FDI from China into Mexico still significantly trails that of the U.S., but also that of Canada, Japan, Germany and Spain (which in 2024 had negative FDI into Mexico for idiosyncratic reasons). On a relative basis, using the private estimates, China’s FDI is still only 10 percent to 13 percent of that from the U.S. over the past several years.

After the U.S., among the largest investors in Mexico's auto sector have been Japan and Germany (Chart 4). Canada has been a leader in Mexico’s mining and energy sectors.

China plays bigger role in new, greenfield investment

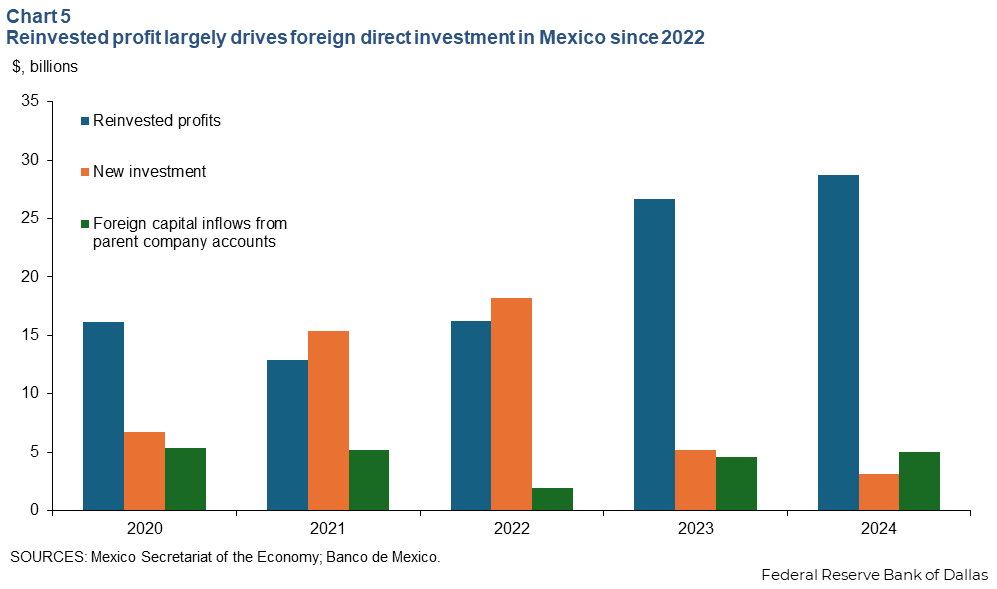

Previous Dallas Fed analysis indicated recent FDI into Mexico has been weak, despite public attention to nearshoring along with global supply chain shifts. Most activity has involved reinvested profits (brownfield investment), with relatively little new investment (greenfield) since 2022 (Chart 5). A large body of research literature shows that, particularly in countries with strong human capital attributes and financial depth, increased FDI can enhance economic growth.

In this context, Chinese FDI may be a larger part of new investment. This weighting toward greenfield FDI could partly explain the high visibility and media attention on Chinese investment in Mexico, even if its aggregate flow and stock remain well below other countries’ activities, based on both official and alternate data estimates.

Chinese investment in Mexico has significantly shifted from mergers and acquisitions to greenfield investments, according to the National Autonomous University data. After 16 merger and acquisition transactions totaling about $7.8 billion from 2015 to 2019, only five such deals valued at $1.7 billion have been completed since 2020. Meanwhile, Chinese companies undertook almost 70 new investments from 2020 to 2024. Rhodium data tell a similar story, with greenfield investments accounting for roughly 85 percent of major FDI transactions from China into Mexico from 2020 through the first half of 2025.

Mexican industrial parks reported 196 new tenants in 2023, 46 percent from the U.S. and 17 percent from China, according to a 2024 survey. Respondents said they expected this proportion to be maintained, highlighting both the predominance of U.S. investment and the growth of Chinese firms.

Despite this influx, Chinese firms made up 4 percent of overall industrial park tenants. A large portion of Chinese investment in Mexico has gone into Hofusan Industrial Park, a large facility near Monterrey, which reportedly houses at least 40 Chinese companies.

Sectoral patterns and regional clustering emerge

Geographically, most of China’s FDI has been in the northern states of Chihuahua, Nuevo Leon and Baja California, contributing to existing industrial clusters for the auto and electronics sectors. Sizeable investments have also gone to Mexico City and the central states of San Luis Potosi and Jalisco.

While there have been some sizeable investments from large Chinese companies, most Chinese investment in Mexico appears to be from small and mid-sized companies, often suppliers of global manufacturers that have asked these small firms to establish presence in Mexico. In many cases, it is also a likely step to nearshoring Asian production and developing suppliers in Mexico to replicate essential supply chains. Roughly 1,000 Chinese companies are registered and operate in Mexico in various industries, according to data from the Mexican Secretariat of Economy.

Foreign companies—particularly small ones, including from China—increasingly use Mexican shelter services to establish manufacturing operations. In Mexico, shelter companies act as legal intermediaries, allowing foreign businesses to set up manufacturing operations in Mexico more quickly and flexibly, without directly incorporating subsidiaries.

The shelter firms can also handle issues such as human resources and regulatory compliance with USMCA standards. The use of a shelter company generally shows up as a service export from Mexico rather than as FDI, adding to the challenges of measuring FDI.

The automobile industry is the dominant sector for Chinese investment in Mexico (as it is for FDI into Mexico overall). The auto sector, mainly auto parts suppliers, accounted for around 45 percent of Chinese investment by value since 2017, according to National Autonomous University data. Rhodium estimates the auto sector makes up just less than 40 percent of Chinese investment. To date, no Chinese auto manufacturers have established production facilities in Mexico.

Mexico’s National Agency of Automotive Sector Suppliers trade group reported 40 Chinese parts suppliers operated in the country as of May 2025, a growing but still small portion of the more than 1,000 auto parts companies in Mexico.

Chinese firms represent roughly 3 percent of Mexican auto parts production, mostly involving electrical systems, starter devices and replacement parts (in many cases for the growing number of Chinese autos in Mexico), according to the trade group’s data. These Chinese companies often provide technology that is unavailable locally or costly to import, the trade group’s president has said. The leader of another group, the National Agency of Automotive Sector Suppliers, has argued that Chinese investment addresses gaps in Mexico’s advanced manufacturing capabilities.

Other key sectors for Chinese investment have been energy, electronics, furniture and equipment manufacturing (Table 1).

| Sector | Chinese Company | Details |

| Energy | State Power Investment Corp. | Bought Mexican renewable energy producer Zuma Energia for roughly $1 billion in 2020. |

| Trina Solar | Announced plans in 2023 to invest up to $1 billion in solar panel production capacity. | |

| China National Offshore Oil Corp. | Invested in offshore exploration blocks in 2019 but exited the investments in early 2025. | |

| Electronics | Haier | Acquired GE appliances in 2016 along with a 48 percent stake in appliance manufacturer Controladora Mabe. |

| Hisense | Announced in 2024 a $250 million investment in its largest refrigerator production site outside China. | |

| Lenovo | Initial investment in 2007, follow-up investment in 2021 in server and computer rack assembly megasite. | |

| Huawei | Invested approximately $65 million in cloud data centers in Mexico since 2019. | |

| Machinery | Lingong Heavy Machinery Group | Invested $140 million for construction of a plant in Nuevo Leon in 2022. |

| Allied Machinery | Began construction in April 2025 of a $250 million machine components plant in Marín, Nuevo Leon. | |

| Furniture | Kuka Home Man Wah |

Invested a combined, estimated several hundred million dollars in Mexico since 2020. |

| NOTE: Plans and costs are announced but not necessarily realized. SOURCES: Company and media reports. |

||

Among Chinese investments that have been announced, some of the most scrutinized haven’t subsequently materialized. Potential plans by Chinese electric vehicle (EV) leader BYD to set up production in Mexico spurred U.S. congressional concern that it would potentially threaten the North American automobile sector. BYD announced in July 2025 it is no longer pursuing the investment, citing geopolitical concerns.

Similarly, Chinese EV battery leader CATL was reportedly considering an investment of up to $5 billion in Mexico in 2022. Those plans are on hold. China’s Ganfeng Lithium acquired the largest lithium deposit in Mexico in 2021, though the next year the Mexican government canceled Gangfeng’s lease.

Policy landscape and comparative international approaches

Mexican state and local officials have largely welcomed Chinese investment and the jobs and industrial development it can support, while the federal government has been relatively more ambivalent. Other emerging market economies have announced investment incentives combined with import tariffs to incentivize Chinese EV manufacturers to produce locally, but with mixed results. Mexico has notably not emulated these measures.

Thailand, Southeast Asia’s leading auto producer, in 2022 announced reduced import and excise duties, along with subsidies, to attract Chinese EV manufacturers. Officials viewed such investment by Chinese market leaders as essential to Thailand’s future competitiveness as the auto sector shifts to EVs. These policies helped secure more than $1.5 billion in investments but have had unintended consequences. Surging Chinese EV imports pressured Thailand’s existing domestic production, resulting in factory closures among auto manufacturers and parts suppliers.

Similarly, Brazil added tariffs on imported EVs (set to reach 35 percent in 2026) while offering incentives and top-level government support for Chinese EV manufacturers to build local production. BYD is constructing a $1 billion manufacturing complex in Brazil. Meanwhile, Brazilian prosecutors sued the company over working conditions during plant construction, delaying full operations.

Turkey increased tariffs on Chinese EV imports in 2024 while exempting BYD so it could invest locally. The investment has yet to materialize.

Mexico has also been laying the groundwork for an investment screening and security review mechanism, similar to a memorandum of intent Mexico’s Ministry of Finance signed with the U.S. Treasury in December 2023 to discuss best practices for developing a foreign investment screening regime in Mexico.

Additionally, Plan Mexico, which President Claudia Sheinbaum announced in early 2025—a partial return to past industrial policies grounded in import substitution—seeks to move from Chinese inputs and increase local and regional value added.

Outlook and recent developments

Chinese investors appear to have become more cautious about Mexico, given increased U.S. and Mexican government skepticism toward Chinese investments as well as uncertainty around U.S. tariffs. This may slow the growth of Chinese investment, even as Mexican local government leaders welcome the opening of new Chinese manufacturing plants.

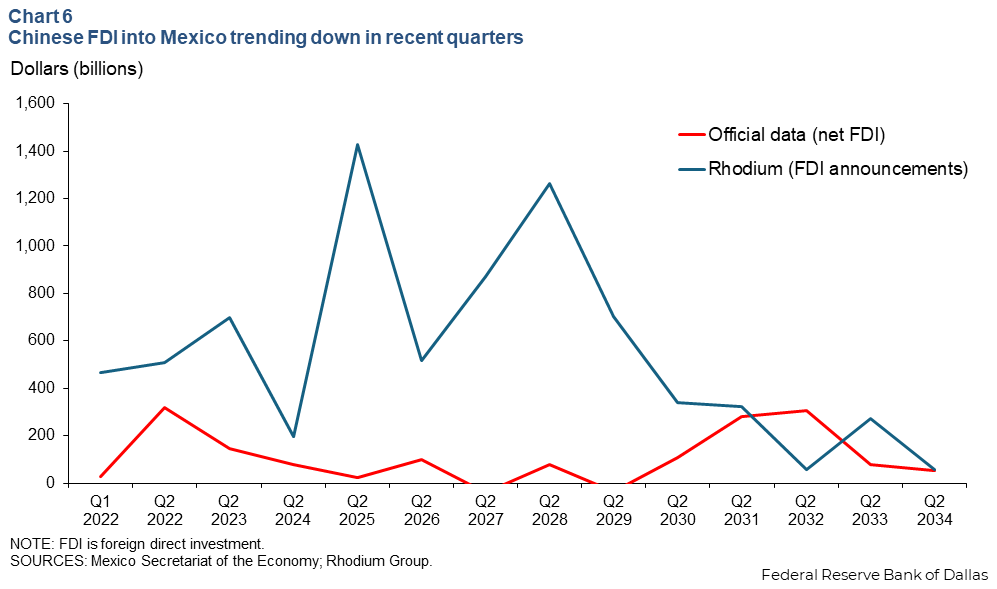

Official data report net foreign direct investment of $76 million from China in the first quarter of 2025 and $54 million in the second quarter. Rhodium Group’s monitoring of individual transactions shows almost $1.1 billion in realized investments in the first half of 2025 (mostly in the auto sector, but also in machinery, electronics and information and communications technology). New FDI announcements have continued, but trended down, to $272 million in first quarter 2025 and $57 million in the second quarter, based on Rhodium’s tracking (Chart 6).

Still unclear is how the policy uncertainty and developments involving USMCA, including review of the trade pact, which began in Septermber 2025, will impact the trajectory of Chinese FDI in Mexico. Chinese companies have reportedly considered exporting more of their Mexican production to Latin America, taking advantage of Mexico’s broad network of regional free trade agreements while also potentially shifting investments outright to South America.

|

This article is part of a series examining China’s evolving trade and investment linkages with North America and the subsequent policy responses. The series looks at Chinese foreign direct investment in Mexico, the impacts of U.S. limits on Chinese imports and the prospects for nearshoring of North American supply chains. |

About the authors