Central bank swaps offer dollar crisis lifeline to non-U.S. banks

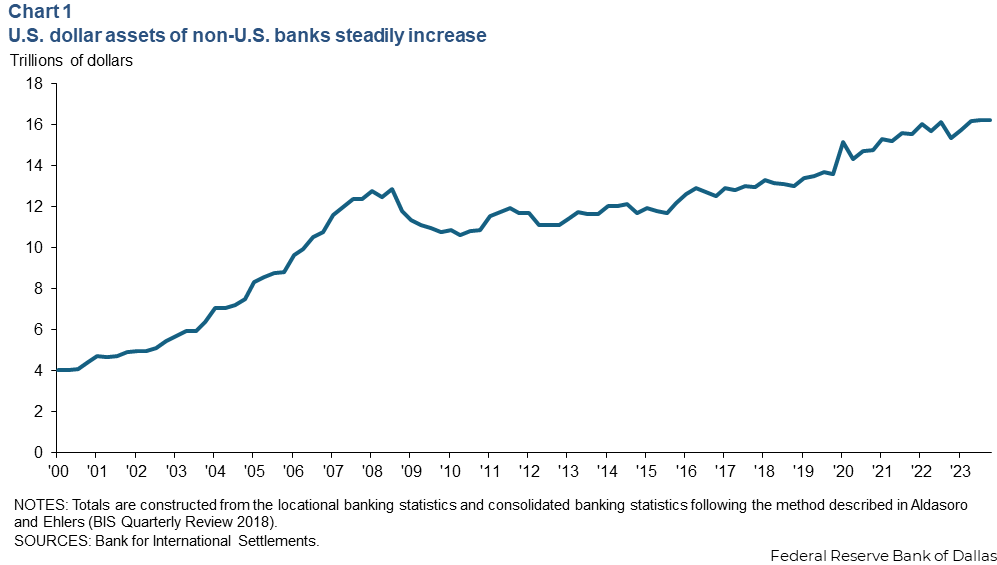

Banks headquartered outside of the United States hold a little more than $16 trillion in U.S. dollar assets (Chart 1). This is of comparable magnitude to the $22 trillion in assets of U.S.-based depository institutions.

A key difference: U.S. banks have access to the Federal Reserve's emergency liquidity facilities, which help support the flow of credit during periods of extreme stress, most recently during the onset of the pandemic in 2020. Foreign banks do not have a U.S. dollar lender of last resort.

Currency denomination of bank balance sheets

A U.S. bank can turn to the Fed's liquidity facilities to smooth out a negative shock to its dollar funding. The situation is different for a non-U.S. bank that lacks this access. Discerning dollar-funding vulnerability is not amply clear. Data on the currency composition of the balance sheet at the bank level do not exist (or at least are highly confidential).

We obtain an estimate by combining data on the currency composition of assets (typically loans and related activities) and liabilities (often deposits and other funding) at the country level from the Bank for International Settlements with balance sheet data for the category of large, non-U.S. global systematically important banks from S&P Global Capital IQ. We then construct approximate balance sheets for these foreign banks that take into account the currency denomination of their assets and liabilities. This provides insight into how these banks adjust their balance sheets in response to negative shocks to their dollar liabilities.

Using quarterly data and a sample of 40 large foreign banks across 14 foreign countries from 2003–22, we identify 22 separate episodes when the four-quarter sum of dollar liabilities of a country's banks fell more than 10 percent relative to the prior four quarters.

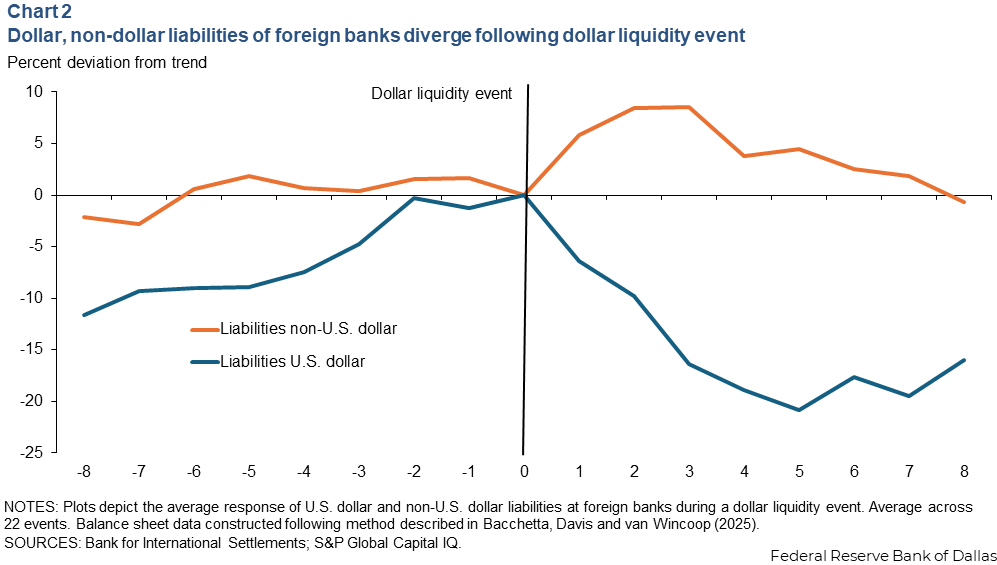

Of these 22 events, seven occurred during the 2007–08 Global Financial Crisis and another seven occurred between 2010 and 2012 during the European debt crisis. Chart 2 shows the average change in bank U.S. dollar and non-U.S. dollar liabilities in the eight quarters before and after these episodes.

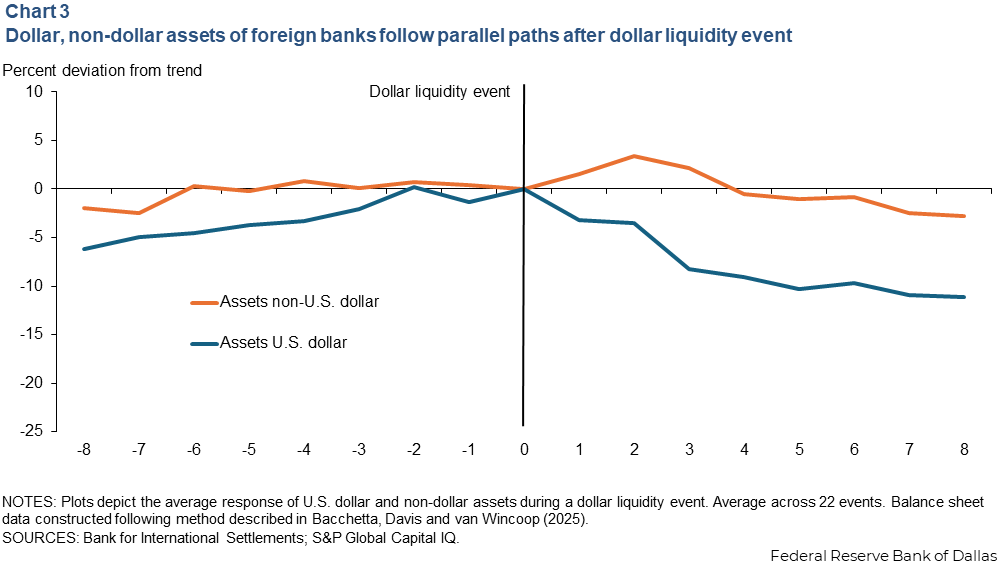

Chart 3 plots the average change in bank U.S. dollar and non-U.S. dollar assets around these same episodes.

On average across these 22 episodes, dollar liabilities fell by close to 20 percent. Dollar assets fell, but only 10 percent. Meanwhile, non-dollar liabilities and assets rose, the latter by only a small amount.

This indicates that banks replaced some lost dollar funding with synthetic dollar funding through foreign exchange swap markets.

Instead of carrying on-balance-sheet dollar liabilities represented in Chart 2, a bank can borrow in its local currency from the local central bank and swap into dollars in the foreign exchange swap market. Alternatively, a bank can construct a risk-free swap by exchanging the local currency into dollars at today's spot exchange rate and at the same time enter a forward contract to exchange it back into the local currency at a future date.

In theory, on-balance-sheet dollar funding and synthetic dollar funding through foreign exchange swaps should be two perfectly substitutable methods of obtaining dollars. We have written previously about how the equivalence between the cost of direct on-balance-sheet dollar funding and synthetic dollar funding through swap markets, known as covered interest parity, held perfectly prior to 2007. It has since broken down.

By increasing local currency liabilities by more than local currency assets, a bank is taking some of its local currency borrowing and swapping it into dollars. This increased synthetic dollar borrowing can then finance the bank's dollar assets, and thus, the bank's dollar assets do not decline as much as its dollar liabilities.

However, frictions in covered interest parity arbitrage mean that when banks perform this swap, the cost of this synthetic dollar funding rises and lessens the swap's attractiveness. It's clear from the data that banks are not treating direct dollar borrowing and synthetic dollar borrowing as perfect substitutes. The bank still cuts its dollar assets in response to a dollar funding shock.

A model of bank stability

Based on this finding, in a recent working paper we construct a model to assess the effect of dollar funding shocks on foreign bank stability. Central to the model: the probability of a bank's default is dependent on the strength of its balance sheet.

During a dollar shock, a bank could face losses from selling assets. In this environment, asset sales in response to a funding shock can lead to losses that deteriorate the bank's balance sheet. This simple fact underpins the need for a central bank to act as a lender of last resort and provide funding during a crisis. However, foreign central banks generally cannot provide dollar liquidity to their local banks, and the Federal Reserve only provides dollar liquidity to U.S. banks.

In the model, there are multiple equilibria and the possibility of a bank-run equilibrium. When the bank's creditors anticipate it will default and not repay its liabilities, they refuse to roll over funding, forcing the bank to sell assets at a steep loss. This itself triggers the default the creditors anticipated. While the local central bank would provide the necessary local currency liquidity to prevent a run on local currency assets, the lack of dollar support means the bank may be susceptible to a run on its dollar liabilities.

We also find that for a sufficiently large negative shock to dollar liquidity, a bank-run equilibrium is the only possible equilibrium. This arises from a feedback mechanism in which a funding shock leads to asset sales, which lead to losses, which raise the bank's probability of default and, thus, funding costs. This produces further losses. Given that foreign central banks cannot generally provide dollar liquidity, the model suggests that a sufficiently large dollar liquidity shock could trigger a dollar bank run at foreign banks.

Dollar liquidity swap lines emerge

Starting in late 2007, the Federal Reserve, in partnership with a few major foreign central banks, began offering central bank dollar liquidity swap lines as an important liquidity backstop.

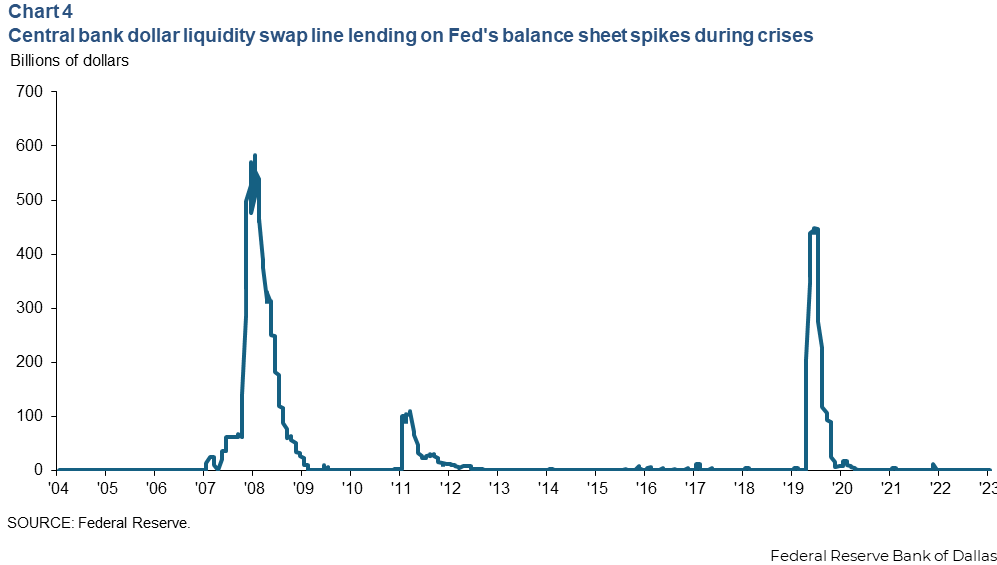

Under this swap line, the Fed provides a short-term collateralized dollar loan to a foreign central bank, which the foreign central bank can then use to provide dollar funding for its domestic borrowers. A swap line can allow the foreign central bank to overcome the key restriction preventing it from providing dollar liquidity to its banks. And, thus, a swap line makes holding dollar assets and liabilities much safer for a foreign bank by enabling its local central bank to become a lender of last resort in dollars. Most of the time the swap line is lightly used. Usage spiked during periods of crisis, such as the Global Financial Crisis in 2008, the pandemic crisis in 2020 and to a lesser extent the European debt crisis in 2011 (Chart 4).

Our model highlights the two ways these swap lines increase the safety of foreign bank holdings involving dollar assets and liabilities.

In the first instance, due to the multiple equilibria and a dollar bank run equilibrium in the model, a swap line can eliminate the possibility of a pure self-fulfilling dollar bank run.

If a bank's creditors know that the bank could tap swap line funding in the case of a run, they are inclined to believe the bank would not face the forced sale of assets if funding via its dollar liabilities were lost. This would, in turn, make creditors less likely to anticipate a bank default and skittish enough to withdraw their dollar funding. The mere existence of the swap line can eliminate the possibility of the bank run, even without the swap line being used.

Second, following a large dollar liquidity shock such as during a major crisis, a stable no-bank-run equilibrium may no longer exist, and the only remaining equilibrium is a dollar bank run. Here swap line lending would be necessary to make sure a sufficiently large dollar liquidity shock does not trigger such a run.

About the authors