Higher tariffs in U.S., Mexico part of global response to China export surge

The average U.S. tariff on imports from China stood at 57.6 percent in September 2025, more than double the level at the beginning of the year, according to the Peterson Institute for International Economics. Heightened trade tensions have been accompanied by elevated tariffs on Chinese goods, which the U.S. and Chinese governments said would be decreased by 10 percentage points following an October summit.

Concerns about transshipment of Chinese goods to the U.S. via third-country trading partners have also figured prominently in 2025 trade deals announced by the federal government. U.S. and Mexican officials have publicly discussed common North American tariffs on China as a possible component of an updated United States-Mexico-Canada (USMCA) trade agreement.

Mexico and Canada have also imposed new tariffs on goods from China, driven by concerns from their domestic industries. In 2024, Canada became the first economy to emulate U.S. tariffs on electric vehicles (EVs), steel and aluminum from China. Mexico has steadily raised tariffs over the past two years on non-free-trade-agreement partners, including China, and proposed significant additional tariffs in September 2025 ahead of the scheduled review of the USMCA.

These tariffs come in the context of escalating trade restrictions from developed and developing economies globally on Chinese exports. Countries are establishing these restrictions amid concerns about China’s surging exports following the pandemic. As higher U.S. tariffs on China continue to reduce China’s import share in the U.S., key global trade questions are which economies will absorb China’s massive goods exports and what challenges this may pose to domestic industrial sectors.

These global dynamics are critical to understanding the outlook for North American trade and trade policy responses as well as the important role they could play in the future of the USMCA. As the U.S. and Mexico seek to boost their domestic manufacturing, managing tariff levels on industrial inputs and intermediate goods essential for manufacturing is of critical importance.

China’s industrial capacity buildup spurs surging manufacturing exports

The U.S. and its North American partners are not alone in increasing trade restrictions on Chinese exports. Trade investigations by World Trade Organization (WTO) members involving China reached an all-time annual high of 198 in 2024, almost half of all WTO-notified trade disputes, according to research by Peking University professor Lu Feng. Lu notes that beyond global trade tensions, the data reflect “a degree of China-specific pressure in the international trade system.”

The European Central Bank cited a historically unparalleled buildup of manufacturing capacity in China spurred by government policy support, including China’s aim to “reduce its reliance on global trading partners by importing less.” With China’s multiyear real estate downturn and the slow recovery of its household consumption since the pandemic, China’s domestic demand has been weak. Meanwhile, the redirection of investment from real estate toward manufacturing has resulted in a surge of production and capacity.

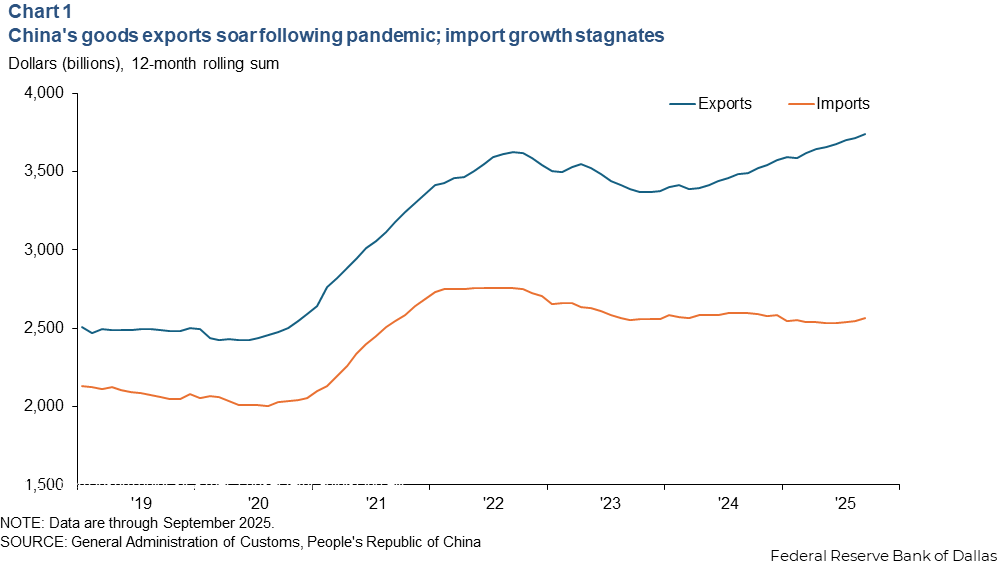

This policy mix has prompted concerns of overcapacity in a number of industrial sectors and broad-based deflation in the economy, with China’s producer price index negative for the past 36 months. With production far outstripping domestic demand, exports have rapidly increased. Simultaneously, imports have contracted in dollar terms, resulting in growing trade surpluses (Chart 1). China’s trade surplus reached $875 billion in the first eight months of 2025 and is set to exceed by 15-20 percent last year’s record of almost $1 trillion for the full year.

There is no standard international definition of overcapacity. Generally speaking, overcapacity, or excess capacity, arises where production capacity exceeds market-based demand. It is exacerbated by market-distorting government policies that enable companies to maintain or expand excess capacity. This leads to an increase in exports, undercutting competitors in other countries. China has experienced recurring waves of such overcapacity.

Thailand, which is close to China and has Southeast Asia’s largest manufacturing sector, has been one of the most negatively affected economies, experiencing significant factory closures in the past two years. In public reports, the Bank of Thailand cited concerns that China’s “dual circulation” policy—designed to make China more self-sufficient domestically while increasing foreign dependence on its output—has reduced imports from Thailand.

Meanwhile, China’s policy support to manufacturing has led to “overcapacity and, thus, the oversupply of goods from China flowing into ASEAN markets,” according to the Bank of Thailand. (ASEAN is the Association of Southeast Asia Nations, a group of 10 member countries.)

Chinese authorities have alternately pushed back on overcapacity claims, and at other times they publicly highlighted overcapacity in sectors such as EVs, batteries, solar panels and steel. More recently, the Chinese government has focused on addressing involution—disorderly price competition that damages industry health—in these industries as well as in petrochemicals, machinery, electronics manufacturing and building materials.

Steel, automobiles become focal points of trade tensions

China’s steel overcapacity has been a focal point of global tension in recent years, as it was leading into China’s last major attempt to address steel overcapacity in 2016. This previous bout prompted the Group of 20 largest economies to establish a forum to address the global impacts.

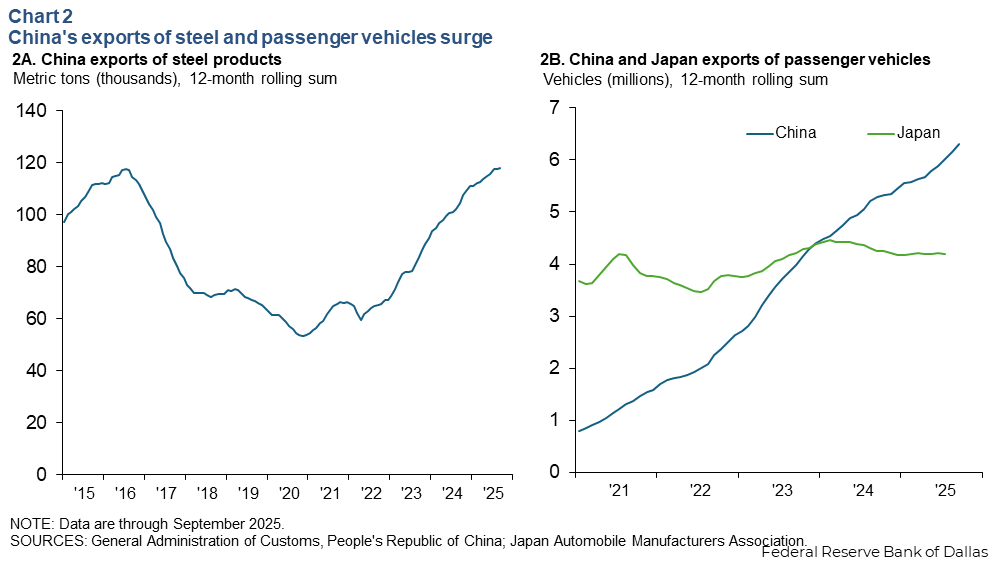

China produces more than half of the world’s steel. As domestic demand for steel in China declined with China’s real estate downturn, production didn’t downshift. China’s steel exports surged in 2023 and 2024, and in 2025 they are exceeding 2016 highs (Chart 2A)

In response, several countries have imposed antidumping duties on steel from China, including the U.S., the European Union (EU), Canada, the U.K., India, Malaysia, South Africa, Thailand, Turkey and Vietnam. In Latin America, Mexico, Brazil, Chile, Colombia and Peru have imposed duties or conducted investigations of China steel products.

China’s auto sector and exports have been additional focal points of global trade concern.

Rapid capacity expansion and production from more than 100 automakers in China have led to price wars domestically and a sharply decline in profitability. Many automakers are selling at a loss, making the sector a focus of Chinese authorities’ anti-involution efforts. China’s auto sales abroad have also surged, overtaking Japan as the largest auto exporter in 2023 (Chart 2B). Almost 3.5 million vehicles were exported in the first half of 2025, according to China customs data.

Major economies that have added tariffs on auto exports from China include the U.S., Canada, the EU, India, Brazil and Turkey. Russia, China’s largest auto export market in 2023 and 2024, in recent months imposed non-tariff barriers to stem auto imports from China and their impact on Russia’s domestic auto sector.

Meanwhile, Chinese auto exports to Mexico surged in recent years. In the first half of 2025, Mexico became the largest export market globally for automobiles from China, importing more than 280,000 autos, China Passenger Car Association data indicate.

Latin America, emerging markets increasingly follow U.S., EU trade response

The U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) announced updated Section 301 tariffs on China in April 2024 targeting unfair trade practices and overcapacity concerns in sectors including EVs, solar cells, lithium-ion batteries, steel, aluminum and foundational semiconductors.

Importantly, the USTR announced an “exclusions” process under which companies can apply for temporary exemptions from tariffs on machinery to be used in domestic manufacturing when tariff imposition might otherwise harm U.S. manufacturing competitiveness.

The European Commission introduced tariffs of up to 45 percent on Chinese EVs in October 2024 and has conducted counter-subsidy investigations in several other sectors, including wind and solar power generating equipment and electric trains.

More than half of the trade investigations last year involving China were by developing economies, however, including in Latin America.

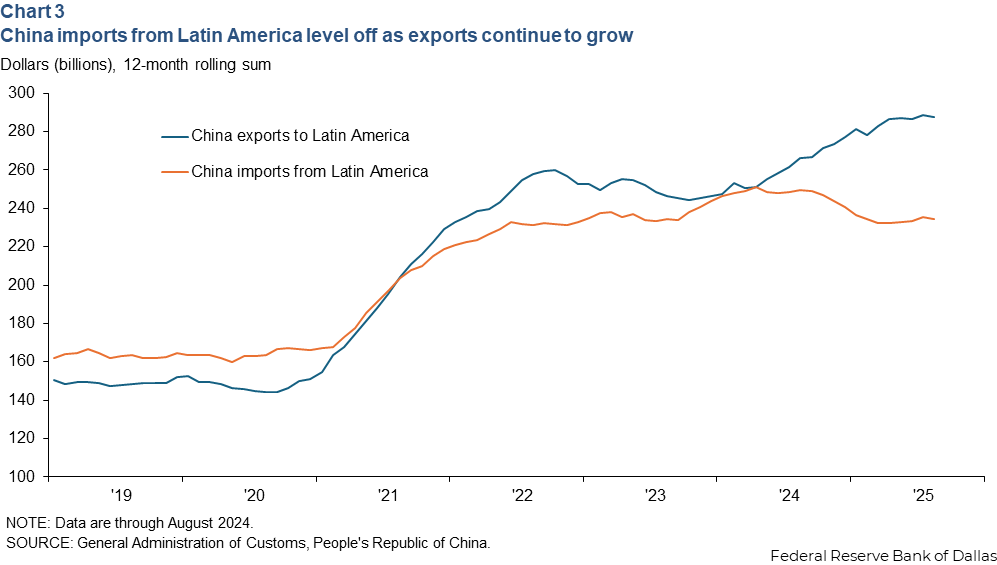

China is the top trading partner for Brazil, Chile and Peru and for South America as a continent. China is the second largest, after the U.S., for Latin America overall. Latin America has enjoyed more reciprocal trade with China than other regions, driven by strong Chinese imports of Latin American commodities. Over the past year, however, Latin America’s exports to China have fallen, while its goods imports from China have risen rapidly (Chart 3).

Brazil notably is one of the few sizeable economies with a trade surplus with China, replacing the U.S. in recent years as China’s largest source of agricultural commodities. A surge of manufactured goods imported from China, however, has heightened concerns from Brazilian industry and escalated the trade response. Brazil has conducted 29 antidumping investigations related to China since the beginning of 2023, covering steel products, fiber optics, medical products and petrochemicals, according to data from Global Trade Alert.

Mexico steadily escalates tariffs, slowing imports from China

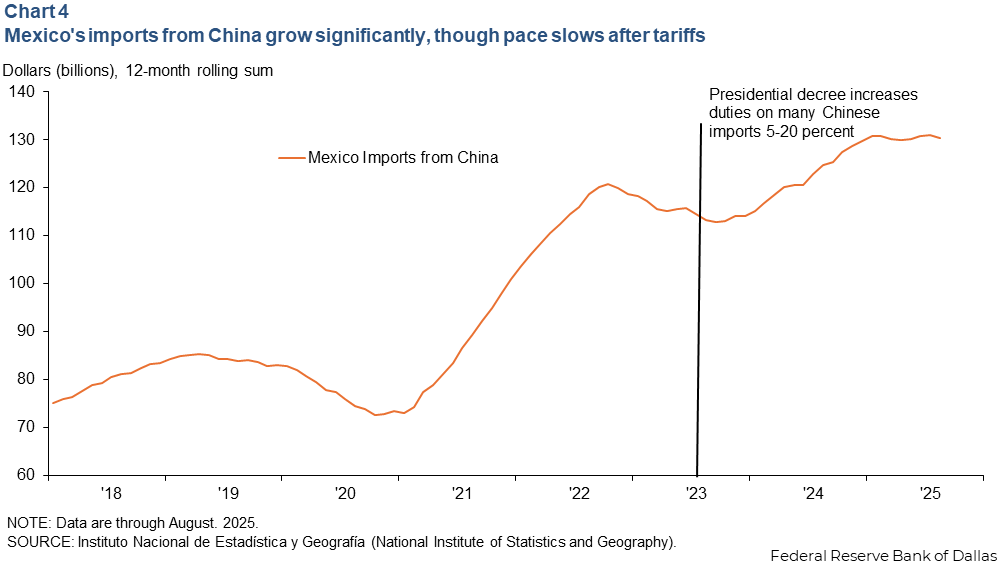

Over the past two years, the Mexican government has steadily increased tariffs on imports from China both to address U.S. concerns and to provide protections for Mexico’s domestic industry as it faces a wave of imported Chinese goods. The trade restrictions appear to have slowed the overall rapid growth of imports from China (Chart 4).

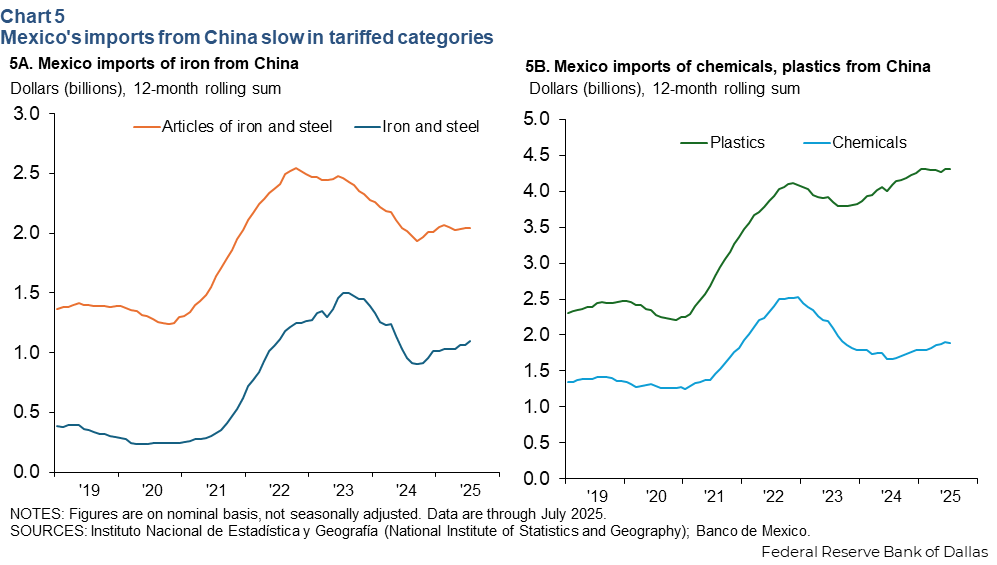

Tariffs have also had an effect in specific sectors, such as steel and chemicals, over a period during which China’s exports to other emerging markets continued growing rapidly (Chart 5).

An initial, August 2023 Mexican presidential decree increased import duties on 392 items by between 5 percent and 25 percent, involving goods originating from countries not party to Mexico's free trade agreements. China is the most significant such country, though the list also includes South Korea, India, Thailand and Turkey. The tariffs covered inputs and finished products produced by key industries such as steel, aluminum, textiles, footwear, tires, plastics, glass, electrical equipment and furniture.

In a subsequent April 2024 presidential decree, Mexico expanded the list of products subject to tariffs—increasing the number of harmonized system (HS codes) from 392 to 544, and raising the maximum tariff rate from 25 percent to 50 percent—though notably not involving the auto sector.

The administration of Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum, who took office in October 2024, has increased tariffs on textile imports from China, emphasizing concerns about job losses in Mexico’s domestic textile industry. Under a December 2024 presidential decree, effective until April 2026, Mexico imposed additional duties of 15 percent to 35 percent on 155 textile and finished apparel items. Mexico also applied a 19 percent tariff rate on products imported through e-commerce sites and courier companies from countries without trade agreements —particularly affecting products from Chinese fast fashion platforms Temu and Shein.

These actions are also occurring in the context of growing U.S. and global pushback on low-cost textile imports from China. The U.S. suspended de minimis treatment (which exempted imports with a value under $800 from tariffs) involving imports from China. The action, effective May 2, 2025, followed growing concern that the de minimis exemption provided a loophole for Chinese exporters. The U.S. subsequently suspended the de minimis exception for all countries.

The EU, Vietnam, Indonesia and Chile, among others, have also in the past year imposed fees or restrictions on low-value imports and the operations of Chinese e-commerce platforms due to concern about their impact on domestic textile manufacturers.

As part of its 2026 budget plan, the Mexican government proposed in September 2025 additional tariffs on non-free-trade-agreement partners, including China, involving roughly 1,463 product categories. This almost triples the breadth of the tariffs announced in the previous decrees, most significantly including autos and auto parts. The tariffs cover 8.6 percent of Mexico’s total imports, according to Mexico’s minister of economy.

The proposal also raises the minimum tariff to 35 percent in most covered sectors and to 50 percent for automobiles, the maximum allowed under WTO rules. The Mexican government projects an increase in tariff revenue of 70 billion pesos ($3.8 billion) in 2026, a roughly 60 percent increase from 2025. Mexico Minister of Finance Edgar Amador tied the planned tariffs to the Sheinbaum administration’s Plan Mexico, which seeks to reduce reliance on imports from China and promote greater domestic value-added through financial and tax incentives.

The government also indicated it would be sensitive to impacts the tariffs may have on production and prices. This will be closely watched as Mexico seeks to boost domestic manufacturing and nearshoring. For example, in May 2024, the government unwound tariffs on raw aluminum from China to avoid negative impact on Mexico’s automotive and electronics supply chains.

The Confederation of Industrial Chambers of Mexico has welcomed the tariffs as a necessary action to create a level playing field, in light of unfair practices such as dumping and subsidies. However, other industry groups, such as the Mexico-China Chamber of Commerce and Technology, and some economists have warned the measures could raise input costs and deter nearshoring efforts that seek to relocate supply chains, mainly from Asia. A number of Mexican economists have additionally criticized the measures as protectionist and said they are bound to mean higher prices for consumers.

Canada was first to emulate U.S. 2024 tariffs on China

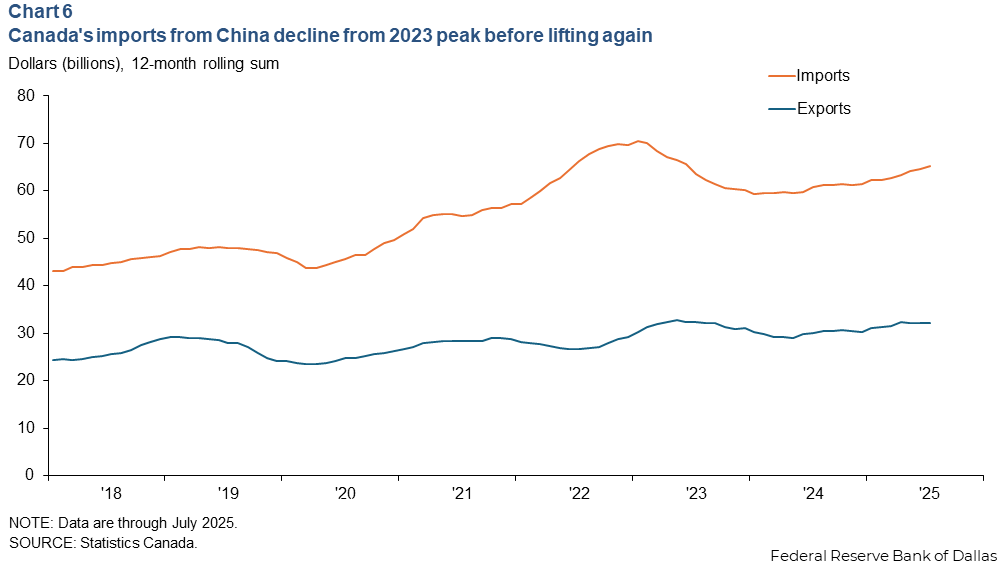

Canada has also experienced trade tensions with China in recent years. Trade with China declined in the past two years after a moderate increase in Canadian imports from 2020 to 2022. China is Canada’s second-largest trading partner, accounting for 8 percent of Canada’s imports in 2024, with the U.S. first, at more than 62 percent, according to Statistics Canada. Overall, Canada’s imports from China rose from $49.7 billion in 2020 to $69.6 billion in 2022 and dipped to $61.5 billion in 2024 (Chart 6).

Along with the E.U., Canada was quick to follow the U.S. tariffs on Chinese EVs. Canada imposed its own 100 percent levy on EVs from China in October 2024 and mirrored U.S. Section 301 tariffs on steel and aluminum from China as well. In retaliation, China in March 2025 imposed tariffs on imports from Canada, including a 100 percent duty on Canadian rapeseed oil and pea imports and a 25 percent duty on Canadian aquatic products and pork. China added a 75.8 percent duty on canola seed from Canada, impacting an estimated 4 billion Canadian dollars in exports in August 2025.

Canada in September 2024 launched a public consultation on imposing its own “potential surtaxes” that would emulate the U.S. Section 301 2024 tariff update in other sectors, including batteries and battery parts, solar products, semiconductors and critical minerals. Canada has yet to implement tariffs on imports from China in these additional sectors, with some speculation that it is holding off pending tariff negotiations with the U.S.

Canada earlier in 2025 took additional action to protect its steel industry from trade diversion following U.S. Section 232 steel tariffs, citing national security concerns. Canada imposed a 25 percent surtax on steel imports containing inputs melted and poured in China effective Aug. 1, 2025, regardless of the raw steel’s country of origin. Canada also implemented new tariff rate quotas, applying a 50 percent surtax on steel imports above 2024 levels from non-free-trade-agreement partners.

U.S. 2025 tariffs reinforce China’s export shift to emerging markets

Following U.S. imposition of additional China tariffs in 2025, analysis has focused on the redirection of China’s exports to third-country markets, both the impact of increased imports from China on domestic industries and on the potential for trade diversion or transshipment to the U.S.

China’s export shift away from the U.S and toward emerging economies may also carry implications for the international monetary system. Recent International Monetary Fund studies have found that the role of the Chinese renminbi in global trade invoicing and trade settlement has grown steadily and expanded beyond Asia. It has spread to Latin America, even as the renminbi’s role remains modest relative to the dollar.

Based on China customs data, China’s exports to the U.S. fell 16.9 percent, in dollar terms, in the first nine months of 2025 from the same period in 2024, even as China’s exports grew 6.1 percent globally. Increased exports from China to the EU—up 8.2 percent from a year earlier—have absorbed an important part of this activity. China’s exports to the U.K. and to Canada, while much smaller than those to the EU, also rose 8.7 percent and 5.1 percent, respectively.

China’s exports have shifted most notably to developing economies, continuing a recent trend. Rhodium Group cites a survey by the China Council for the Promotion of International Trade showing that 75 percent of the Chinese exporters surveyed intend to expand into emerging markets to compensate for shrinking exports to the U.S.

China’s exports to ASEAN (now its largest export market overall) rose 14.8 percent in the first nine months of 2025, while exports to India rose 12.9 percent and to Africa increased 28.2 percent. China’s exports to Latin America also continue to grow, up 7.0 percent.

China’s exports to Mexico, by contrast, fell 3 percent in the first nine months of 2025, based on China customs data. Mexico’s additional proposed tariffs could further slow imports from China in large categories such as automobiles but may incentivize some front-loading of imports before the tariffs take effect.

|

This article is part of a series examining China’s evolving trade and investment linkages with North America and the subsequent policy responses. The series looks at Chinese foreign direct investment in Mexico, the impacts of U.S. limits on Chinese imports and the prospects for nearshoring of North American supply chains. |

About the authors