Texas metro unemployment rates drop but remain above early 2020 levels

Unemployment rates across Texas metros have come down quickly since the pandemic recession of 2020, though they remain above preoutbreak levels.

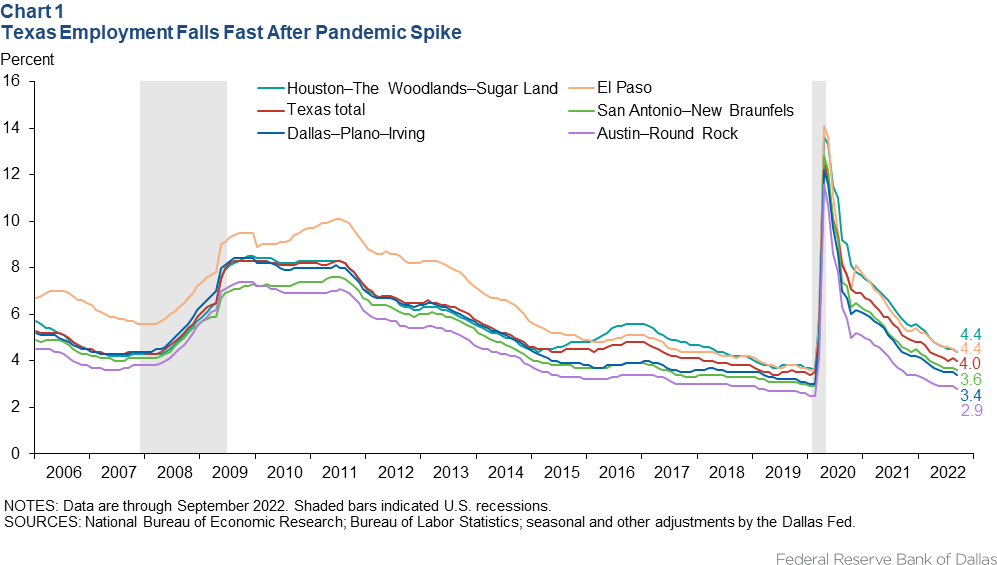

The Texas unemployment rate shot up to 12.6 percent in April 2020 after the sudden loss of over 1.4 million jobs following shutdowns implemented to limit the spread of COVID-19. While the pandemic peak unemployment rate was higher than during the Great Recession, the recent recovery has been faster, with the jobless rate dropping 8.6 percentage points in 29 months (Chart 1).

The overall state jobless rate was 4.0 percent in September.

Workers are classified as unemployed when they don’t have a job but are actively seeking one. The most cited unemployment rate, U-3, is the number of unemployed workers divided by the labor force (the sum of all workers—employed and unemployed).

The unemployment rate falls as unemployed workers either find jobs or leave the labor force. In Texas’ case, the decline is due to the unemployed returning to work, with job growth being very strong. Employment in September was 4.5 percent above the prepandemic level.

Among all Texas metros during the month, McAllen had the highest unemployment rate, 7.1 percent, while Amarillo tied with Austin for the lowest at 2.8 percent.

Before the pandemic, in February 2020, McAllen also had the highest unemployment rate (6.3 percent), while Austin (2.5 percent) had the third-lowest rate and Amarillo (2.4 percent) the second lowest. Midland, in the heart of the oil-rich Permian Basin, had the lowest unemployment rate in February 2020 (2.2 percent). The Midland rate has since risen to 3.2 percent, the fourth lowest in the state and trailing No. 3, College Station, at 3.0 percent.

Assessing Differences

Industry composition and demographics explain many regional unemployment rate differences. Metro areas with large concentrations of thriving, high-wage industries tend to have faster job growth and lower unemployment. Conversely, jobless rates tend to be higher among young and less-educated workers than those who are relatively older or highly educated. Unemployment among Black and Hispanic workers also tends to be higher.[1]

Austin’s tech boom has added new high-skill jobs, keeping unemployment low. The border metros, on the other hand, skew younger and less educated, with lots of retail jobs and a lower share of high-tech and professional services employment.

Houston’s concentration of energy jobs explains its relatively high unemployment rate. The oil and gas sector is one of two sectors statewide that have not bounced back to prepandemic employment levels. (Government was the other laggard.)

Though Texas employment returned to its prepandemic level by November 2021, the unemployment rate remains above where it stood before COVID. Even with employers continuing to report difficulty finding qualified workers, the jobless rate in all major Texas metros still exceeds February 2020 levels.

One reason is rapid labor force growth through natural increase and migration. Employers are hiring at a rapid rate, attracting still more people to the workforce.[2], [3]

Notes

- “Spotlight: Black Workers at Risk for ‘Last Hired, First Fired,’” by Aquil Jones and Joseph Tracy, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Southwest Economy, Second Quarter, 2020.

- “Texas Joblessness Persists Above U.S. Rate, Weighing on Black, Hispanic Workers,” by Anil Kumar, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Southwest Economy, Fourth Quarter, 2021.

- “Largest Texas Metros Lure Big-City, Coastal Migrants During Pandemic,” by Wenli Li and Yichen Su, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Southwest Economy, Fourth Quarter, 2021.

About the authors

Articles may be reprinted on the condition that the source is credited to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.

Full publication is available online: www.dallasfed.org/research/swe/2022/swe2204.