Overflowing U.S. shale gas increasingly streams to Mexico and onto global markets

U.S. natural gas production has boomed over the past 15 years while Mexico’s output has steadily declined.

Huge volumes of imported shale gas from the United States have provided ample supply for Mexico’s growing energy needs, keeping power prices down for industries and households. Future plans envision continuing supplies to Mexico and export sales largely to Asia using liquefied natural gas terminals on Mexico’s west coast.

Permian Basin overflows with natural gas

Before the natural gas flowed in abundance, scarcity ruled the market.

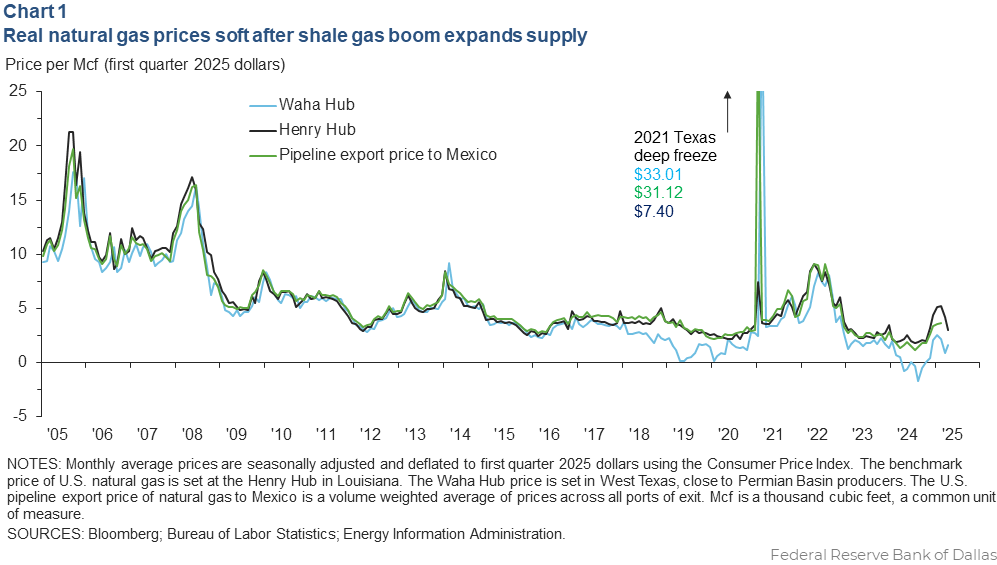

Natural gas prices were at historic highs in the late 2000s. The U.S. and Mexico began preparing to import increasing quantities of natural gas from around the world. The U.S. benchmark price for natural gas at the Henry Hub had climbed from an average of $5.28 per thousand cubic feet (Mcf) on an inflation-adjusted basis from 1993–2002 to $9.75 over the two years that followed. It reached an average of about $12 between 2005 and 2008 (in first quarter 2025 dollars).

Moreover, natural gas prices routinely spiked with hurricanes (Katrina and Rita in 2005 and Ike in 2008), cold winters (February 1996 and 2003, December 2004 and 2009), hot summers, unplanned infrastructure outages and broader commodity market movements. There was little slack in the market (Chart 1). The U.S. and Mexico began building LNG import terminals on the assumption that the U.S. was about to run out of affordable gas and needed import capacity.

High prices from 2004–08 drove up Texas and New Mexico’s production more than 25 percent from a near 50-year production low in 2004. Mexico's domestic production expanded more than 50 percent during the period, according to Petroleos Mexicanos (Pemex) data.

Then, the Great Recession (2007–09) hit, depressing prices.

As global energy commodities rebounded from lows in 2009, burgeoning new U.S. shale gas supplies tempered gas prices. Henry Hub reached the then-historic low of $2.71 per Mcf in 2012, when a mild winter further eased demand.

Surging supplies began overwhelming Texas’ capacity to process and pipe natural gas to consuming regions. The Waha Hub price in West Texas, close to Permian Basin wellheads, followed Henry Hub down until 2017, when the region’s gas pipeline and storage infrastructure ran short of capacity. The Waha gas price subsequently averaged $1.84 from 2018–19, half the price at Henry Hub.

By 2023, Texas and New Mexico natural gas production reached 102 percent of 2004 levels, 35.6 billion cubic feet per day. Production in the rest of the U.S. jumped 76 percent to 68.9 billion cubic feet per day.[1]

Natural gas in Waha is now frequently priced below zero, meaning producers pay to be rid of it. This occurs when production exceeds the capacity to pipe the gas to consumers or LNG facilities, when local equipment fails or even during routine infrastructure maintenance. Every incremental bit of new pipeline in Texas has provided only temporary respite for Texas producers who often sell their natural gas at a loss in order obtain more highly valued oil.

U.S. supplies most of Mexico’s natural gas

Exports are essential for West Texas and New Mexico, where oil production would be limited without the ability to ship the co-produced natural gas to consumers. In the past, excess gas could be flared off for a time. However, environmental regulations have limited the practice.

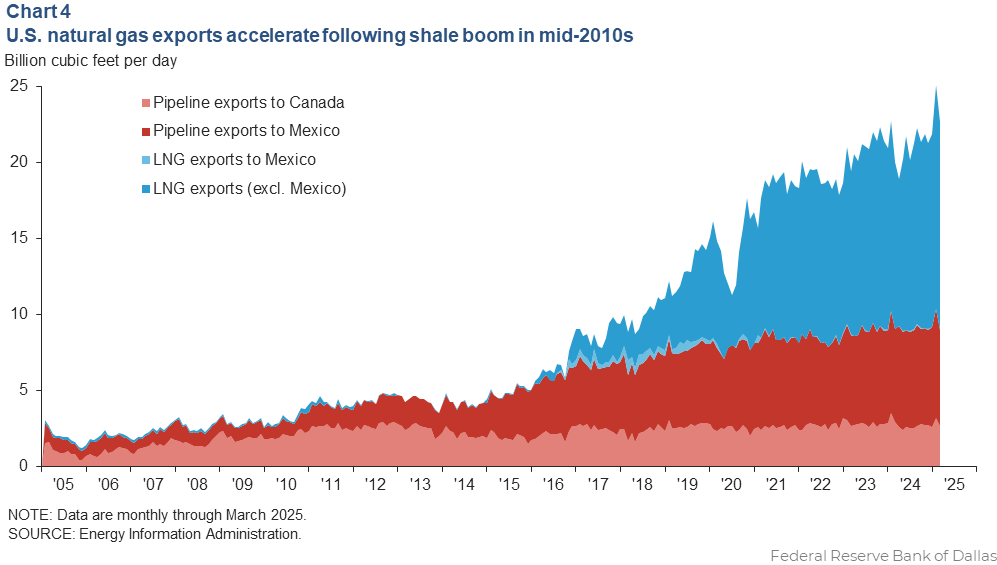

Booming U.S. supplies (at relatively low prices) drove a surge in LNG exports to the world and significant increases in pipeline exports to a growing Mexican market.

From 2008 to 2015, North American natural gas went from among the more lucrative assets in an oil producer’s portfolio to one of the least valuable. Pemex, with a near monopoly on domestic energy supplies in Mexico, struggled to keep pace with accelerating natural gas demand when prices were high.

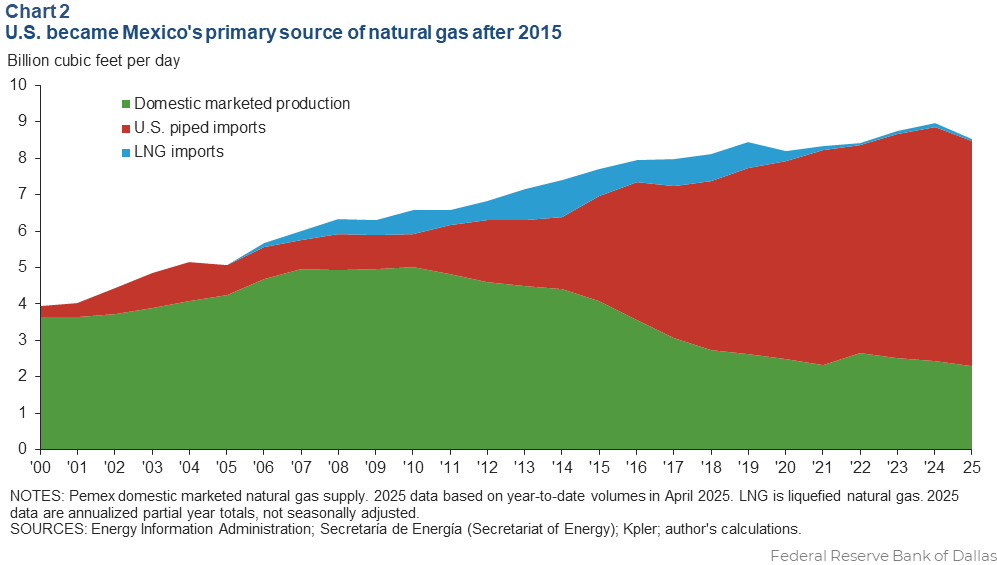

Once prices plummeted, expanding became doubly challenging. Mexico’s domestic supply of natural gas to consumers fell from about 5.0 billion cubic feet per day in 2010 to 2.4 billion cubic feet in 2024. Imports of U.S. gas surged, displacing local production and meeting incremental demand growth (Chart 2).[2]

Absent the high prices of the early 2000s, Mexico became increasingly dependent on low-cost U.S. shale gas. Mexico's pipeline imports across its northern border (mostly from Texas) rose from a trivial share of Mexican supply in the early 1990s to more than 7 percent of the total in 2000. That share doubled to 14 percent by 2010. It doubled again by 2014, and again by 2018. By 2024, Mexico sourced almost 72 percent of its total natural gas supply from the U.S.

Since most natural gas is used to generate electricity, the resulting relatively stable power prices are a clear benefit to Mexico. From 1994 to 2024, 90 percent of the growth in Mexico’s gas consumption came via the power (electricity) sector, amounting to two-thirds of total natural gas consumption. Natural gas powered only 15 percent of Mexico’s electric generation in 1994. That share rose to 36 percent in 2004 and to 55 percent in 2023.

Natural gas, in addition to powering total electricity supply, also displaced older, less efficient and more polluting crude-oil and coal-fired generation.

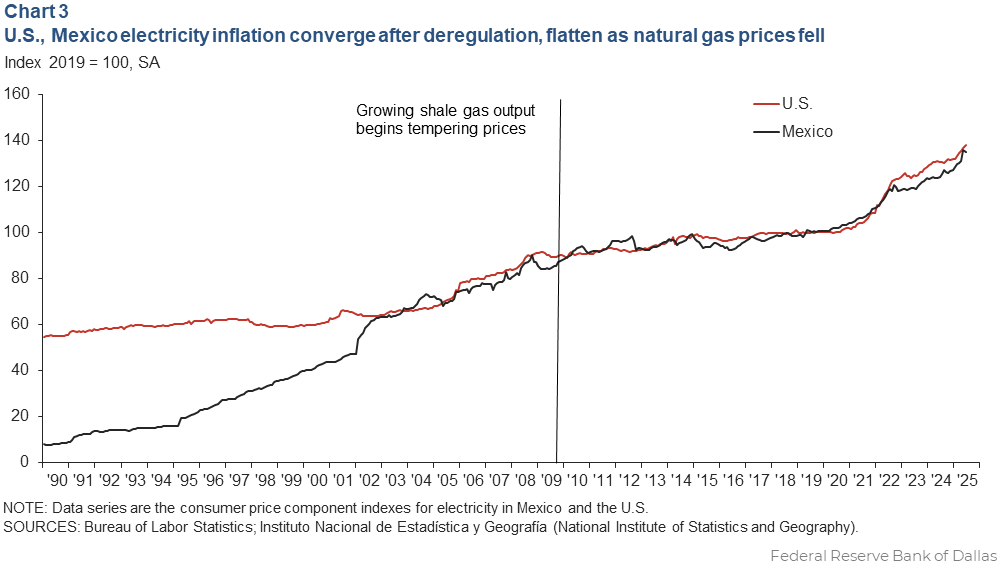

Additionally, natural gas is the primary source of last-unit energy that comes online to meet electricity demand that fluctuates during the day, month and even year. As such, natural gas prices significantly affect the cost of electricity. Mexico’s electricity costs outpaced those of the U.S. in the 1990s, then surged when subsequent regulatory changes allowed greater pricing flexibility. A further policy shift in 2002 allowed prices for many customers to more accurately reflect the increasing cost of producing it.

The shale boom helped flatten the growth rate of electricity costs in the U.S. and Mexico by the 2010s. Costs in the two countries synched with one another despite significant differences in the mix of power generation types and trends in total consumption growth.

Annual consumer price index electricity inflation in Mexico slowed from 4.7 percent (December 2003 to December 2010) to 1.3 percent (December 2010 to December 2019). In the U.S., it slid from 5.4 percent to 1 percent (Chart 3). That’s a far steeper slowdown than occurred in total inflation in either country.

Mexico’s domestic gas production investment lags

Mexico’s industrial sector—durable goods such as primary metals and non-durable goods such as chemicals—accounted for most of that nation’s natural gas consumption growth, aside from electricity. Mexico became a vital North American manufacturing hub after the implementation of the North American Free Trade Agreement in 1994.

Pemex has been unable to meaningfully increase domestic natural gas supplies in more than 15 years, despite growing demand. The national oil company has suffered from financial difficulties as well as a variety of structural, governance and political uncertainties contributing to steadily eroding domestic gas production investment in the increasingly open marketplace.

Several constitutional reforms in 2013 sought to modernize Mexico’s energy sector, allowing private investment in the oil and gas industry. This should have upended Pemex’s monopoly and ostensibly resulted in increased investment in energy infrastructure, including exploration, pipelines and production.

Foreign direct investment in Mexican energy surged, reaching a 20-year high in 2017, encouraged by the high oil prices from 2011–14, growing industrial demand and reforms from 2013–18. Outsized shares of this investment went to the states of Aguascalientes, Veracruz and Tamaulipas.

Countering this surge, the 2015–16 oil bust severely depressed oil prices and damped private investment in Mexico. In the years since, a counter-reform movement secured the dominance of Pemex again, reamplifying regulatory uncertainty and disincentivizing private investment.

These forces contributed to a 51 percent drop in Mexico’s domestic gas supply from 2010 to 2024. Preliminary data for 2025 suggest the general path of decline continues.

As investment eased, Mexico’s proven reserves of natural gas (the estimated volume of resource that could plausibly be produced using current technologies under existing economic conditions) fell from 15 trillion cubic feet in 2004 to about 7 trillion cubic feet by 2023, according to International Energy Agency data.

Could Mexico become an LNG exporter?

Mexico and Canada together imported an average of about 4.3 billion cubic feet per day of piped natural gas from the U.S. in 2012. Paced by exports to Mexico, the two countries accounted for 9.1 billion cubic feet per day in 2024. Meanwhile, U.S. LNG exports to the rest of the world via cargo ships rose from zero to 11.9 billion cubic feet per day during the period (Chart 4).

A wide price gap between U.S. and global prices aided the growth. Henry Hub averaged about $2 per Mcf (nominally) in 2024 compared with the Netherlands TTF hub price for Europe of $11 and the Japan-Korea Marker from Platts, the Asian benchmark, at $11.90.

Nonetheless, despite rising domestic consumption and billions of dollars in new pipeline capacity, Permian Basin producers still face limited takeaway capacity that has kept the price of Waha gas stuck near zero in the past two years. Several new gas pipelines in Texas are in the works to relieve bottlenecks and supply new U.S. LNG export terminals planned for the U.S. Gulf Coast by 2030. These facilities could take in 14.4 billion cubic feet per day of natural gas from producers who also anticipate supplying more gas into Mexico.

Mexico figures in efforts to expand storage and distribution capabilities for new customers in Mexico as well as to anticipated Pacific Coast LNG export terminals. The terminals could supply Asian markets, with shippers of Texas natural gas avoiding the Panama Canal or sailing around Cape Horn.

Other planned projects include the 2.6 billion-cubic-feet-per-day Sur de Tejas-Tuxpan line from Brownsville, Texas, to Veracruz, Mexico, a refining and petrochemical industrial center on the central Mexican Gulf Coast. The Sur de Tejas pipeline beneath the Gulf of Mexico was completed just before the pandemic, though it operates well below its specified capacity. The separate Wahalajara system of interconnected pipelines brings natural gas from the Permian Basin's Waha Hub directly to west-central Mexico, near Guadalajara.

The Sur de Tejas line has been used to supply the first of two floating LNG facilities, the Fast Altamira LNG project, with a capacity of 0.2 billion cubic feet per day. The floating platform, an offshore port where very large gas carriers moor, completed its first LNG cargo delivery to the Netherlands in October 2024.

Completion of a second similar LNG facility on the Baja California Pacific Coast is behind schedule. The delay is attributable to a combination of cost overruns, labor availability issues, productivity and financial challenges, lawsuits, and re-export permitting issues from the U.S. government.

These challenges and the recent history of rescinded energy reforms have limited investor interest and cast doubt about the future of additional proposed Pacific Coast LNG export terminals that could add 6.1 billion cubic feet per day of capacity.

Balancing opportunity and vulnerability

The capacity to import U.S. natural gas is of considerable benefit to Mexico but carries risk. Increasing dependence on U.S. natural gas leaves Mexico vulnerable to large unplanned outages such as occurred during the Texas deep freeze of February 2021. During the storm, prices for natural gas skyrocketed as pipeline pressures dropped across the state system due to failing pump stations and freezing wellheads.

Domestic sourcing and increased storage capacity could help mitigate such impacts but would likely prove prohibitively expensive. Mexico held less than 2.4 days of inventory in 2024, far less than the U.S. at 107 days. The difference is in part attributable to minimal winter heating demand in Mexico.

The upside price risk from rising LNG exports to both nations' consumers is another concern. However, so long as U.S. gas production is not constrained—by a lack of pipelines, for example—U.S. LNG exports and re-exports from Mexico will more likely start running out of international demand before the U.S. runs out of supply.

U.S. natural gas growth is projected to slow through 2030, as shale oil production plateaus in the Permian Basin. Futures contracts and industry analysts expect Henry Hub will average between $3 and $5 over the period. Even with growing domestic electricity demand—including from artificial intelligence computing-driven electricity—the U.S. is unlikely to quickly burn through what's estimated to be 130 years of recoverable economic natural gas reserves. Whether by pipe or LNG, some of those supplies will likely find consumers outside the country.

Notes

- Gas for export or piped to consumers in both the U.S. and Mexico includes some ethane.

- Domestically sourced natural gas for consumption includes small amounts of ethane. It excludes hydrocarbon gas-liquids, such as propane and butane, which are spun off at gas processing plants.