As population trends shift, where will future workers come from?

Population is a fundamental determinant of a country’s productive capacity. More specifically, labor, along with capital and the efficiency with which the two can be combined (total factor productivity) determine how much a country can produce at any point in time.

The United Nations in 2024 revised its World Population Prospects report, which tracks and projects populations across the world, much as the Census Bureau does in the U.S. In 2023, the global population reached 8.1 billion people, up almost 1 billion in the past decade. Despite this growth, many developed (and some developing) countries are experiencing population stagnation or decline, and with it come implications for future productive capacity.

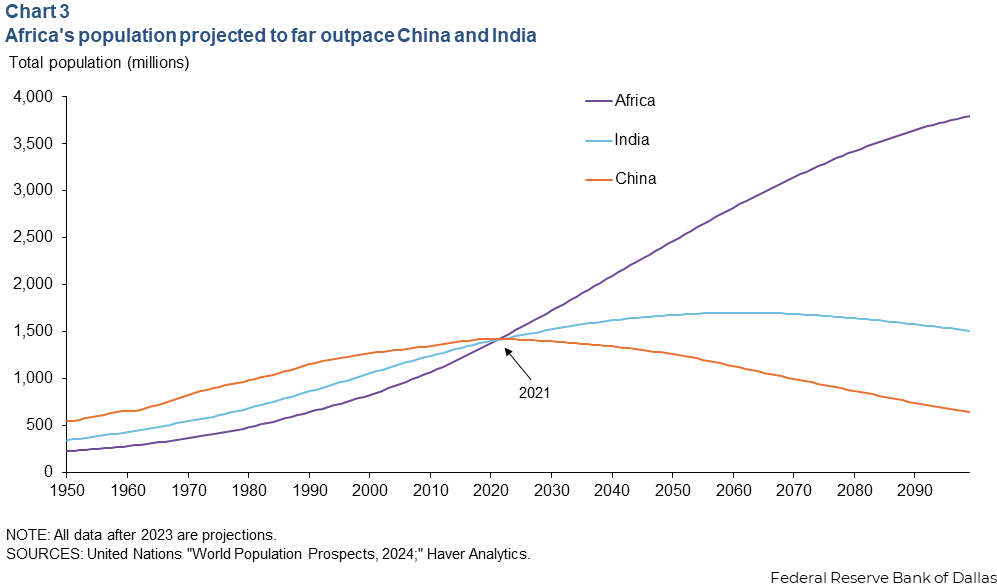

Three major regions of the world, China, India and Africa, had similar populations in 2021, but now face dramatically different outlooks. Differences in the fertility rate, a major determinant of the size of population, play a key role.

The UN projects population shifts

The UN has been producing population projections for many countries and regions since 1951. The raw data come from recent census and national population registration systems.

As the UN notes, “Making projections to 2100 is subject to a high degree of uncertainty, especially at the country level.” That said, in general, the population projections produced by the UN are regarded as highly accurate, though they are viewed as more reliable over short horizons than for longer ones and better for large countries and regions than smaller ones.

Three factors determine population change

There are three fundamental determinants of a country’s population growth: the birth or fertility rate, the death or mortality rate and international migration. In general, both fertility and death rates decline as countries develop.

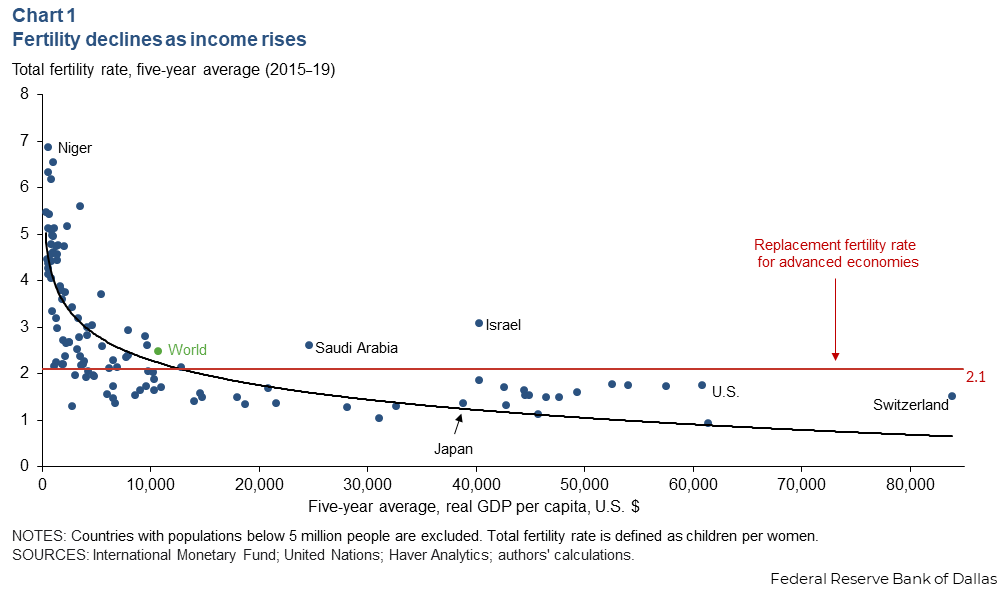

Of these three determinants, shifting fertility rates worldwide seem to be a major factor in the striking changes in population prospects in recent years. Fertility declines as incomes rise (Chart 1) . Fertility also declines with female educational attainment and female labor force participation, both of which are highly correlated with per capita income.

The fertility rate in many advanced economies trails the replacement fertility rate of 2.1 children per woman needed to keep population constant. The U.S. fertility rate has been below replacement for some time, though immigration has been an offset, allowing the U.S. population to continue growing.

The negative correlation between income and fertility rates is a long-standing fact in demography. In recent years, fertility is falling not just with income but at almost all income levels, exacerbating this dynamic.

Further, efforts by governments to bolster fertility rates have had little success.

Population decline brings economic consequences

Population decline is a long-run economic concern because it is a fundamental determinant of a country’s productive capacity. The labor force is a subset of the population. Long term, the labor force cannot grow if the population is shrinking, absent immigration. Population decline eventually means a declining workforce.

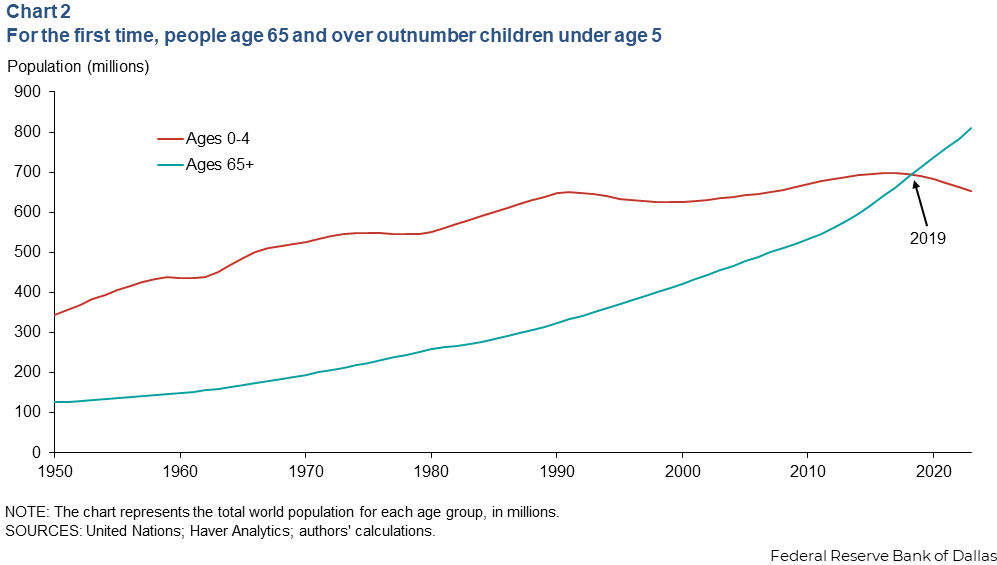

Broadly speaking, population structure refers to a population’s age and gender mix. A rise in the median age worldwide has put a strain on working-age people who must now support more significant dependent populations—those in the age groups that are too old or too young to work.

The dependency ratio is typically defined as the ratio of those under age 15 plus those 64 and older relative to the working-age population, traditionally defined as those age 15 to 64. Today, retirees largely comprise the dependent populations in many advanced economies. For the first time in history, people 65 and older outnumber those age 0–4 (Chart 2).

China, India and Africa population trends diverge

A case study of three major countries or regions, China, India and Africa, illustrates these population dynamics. China is the world’s second-largest economy (and potentially on track to become the world’s largest in the next decade), Africa is a region that has largely missed out on globalization, and India is a large economy in between.

The populations of China, India and Africa were roughly the same in 2021, according to the UN. However, the population projections for these three areas dramatically differ (Chart 3). The explanation is a story of development, fertility rates and failed government intervention.

China’s low birth rate is in large part a legacy of the country’s One-Child Policy, in place from 1980–2015, depressing the birth rate significantly. The policy originally aimed to curtail the expansion of a population that was believed to be unsustainable.

However, the effort far overcorrected, and now China’s population is declining. Even after the policy’s repeal, its effects linger.

Additionally, studies suggest that China is among the most expensive places in the world to raise a child. The economic burden has caused many couples to have fewer children. China has also experienced increased economic development and urbanization, also linked to its declining fertility rate.

Similarly, India’s population is projected to fall soon, despite its current growth. India, like China, has experienced a declining fertility rate coinciding with rising levels of education and urbanization and decreasing poverty rates. As India continues to develop, the population is expected to decline.

China’s fertility rate declined with increased economic development and urbanization; India’s will fall when it reaches similar levels of development. India has already surpassed China as the world’s most populous country. Declining fertility rates are the key determinant of both countries’ population decline.

In contrast, Africa, which has largely missed out on some key aspects of globalization, has a high fertility rate and remains very poor by global standards. Moreover, many African cultures value large family sizes, and Africans have less access to modern contraceptives and good family planning services than people in other regions. Together these characteristics further favor high birth rates.

Considering the stories of China, India and Africa together, income and development commonly affect fertility rates of each region and, therefore, population. Dissimilar economic scenarios, reflected in an area’s income, lead to different fertility rates and ultimately population. As fertility rates decrease and dependency ratios rise, productive potential will be limited and the burden on working-age populations will increase.

A future with fewer births

In many advanced economies, fertility is now below replacement, which means the populations of these countries are either declining or will start declining soon. Strikingly, the same is also true of China, which is still considered an emerging-market economy. While partially a legacy of the One-Child Policy, the shrinking population is now a product of the increased cost of child rearing and changing social norms.

By contrast, fertility remains high in Africa, and based on current trends, the continent will account for more than one-quarter of the world’s population by 2050. It is, thus, poised to contribute an increasing share to an important input to global production.

About the authors