China debt overhang leads to rising share of ‘zombie’ firms

China’s private sector debt ballooned from 2008 through 2016, among the largest and most sustained such increases historically. Notably, this Chinese credit growth was financed entirely from domestic savings, unlike many examples of rapid credit expansion elsewhere.

There is mounting evidence of “zombie lending” in China, banks rolling over bad loans to unprofitable firms and allowing the status quo to continue rather than recognize losses.

In many ways the current experience in China mirrors that of Japan in the 1980s and 1990s. Rapid growth in private sector debt—also fueled by domestic savings—was followed by the appearance of zombie lending. In Japan, that zombie lending led to the inefficient allocation of capital and decreased productivity, especially in sectors shielded from foreign competition.

Chinese credit financed by domestic savings

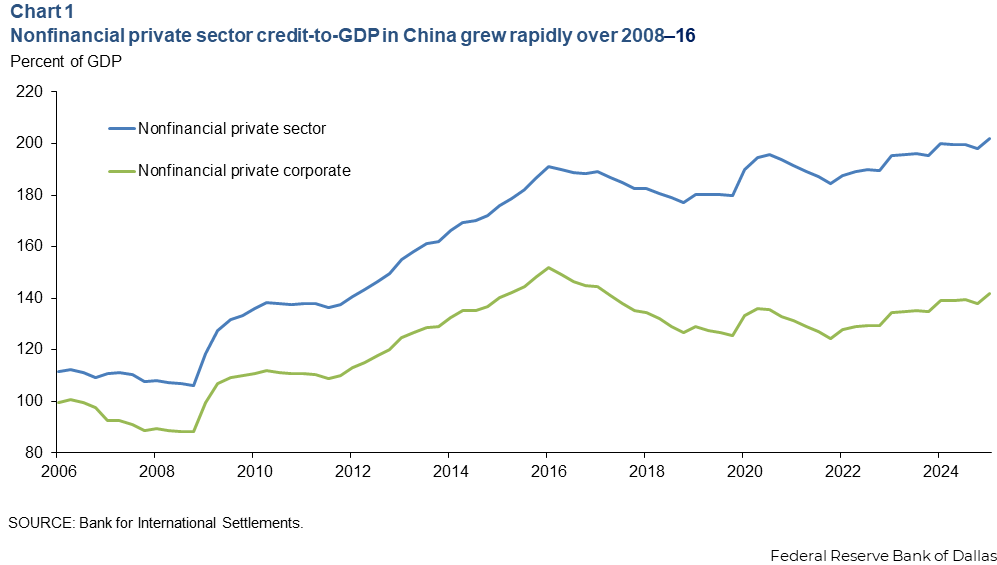

China experienced a massive credit boom following the Global Financial Crisis (2007–09). The ratio of China’s nonfinancial private sector credit to GDP jumped from 106 percent to 188 percent over the eight-year period ended in 2016. About two-thirds of this credit growth is attributable to high levels of corporate credit, which rose from 88 percent to 145 percent of GDP (Chart 1).

Foreign borrowing partly financed many other recent global examples of rapid credit growth. They include credit expansion in East Asian countries in the 1990s, in the eurozone periphery prior to the euro crisis (2010-12) and even in the U.S. and the U.K before the Global Financial Crisis.

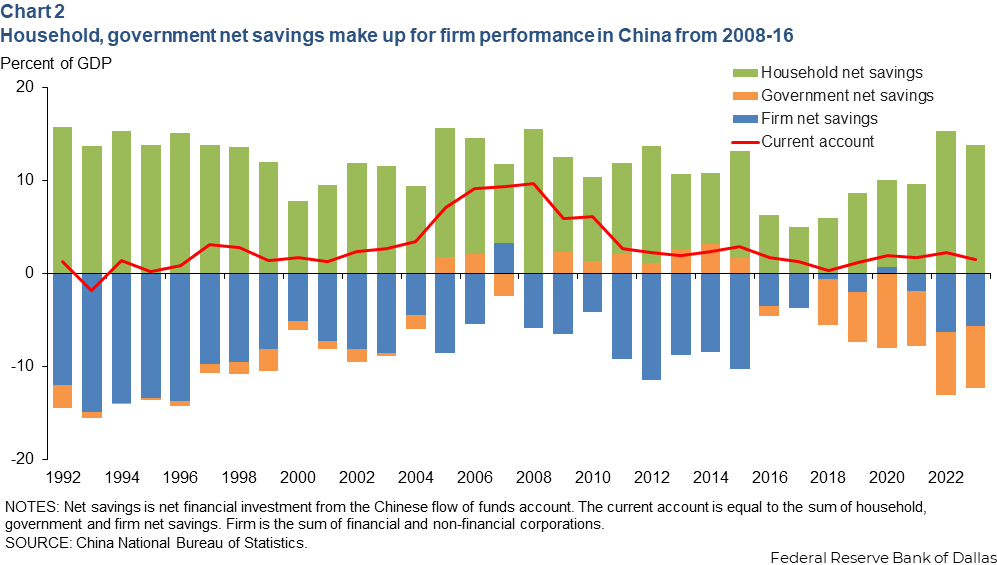

A significant current account deficit accompanied each of these episodes of rapid credit growth. Unlike those examples, China has run a current account surplus every year since the early 1990s (Chart 2).

During the 2008–16 period of rapid corporate credit growth, the negative net saving by the Chinese corporate sector was more than made up for by positive net saving in the household and government sectors.

Papers explore credit growth-crisis link

In the wake of the Global Financial Crisis and the European Debt Crisis (2008–12), many papers in the economics literature indicated that periods of rapid credit growth tended to increase the probability of a crisis.

A 2016 article found that the effect of rapid credit growth on the probability of a crisis depended on a country’s current account balance during the period.

Empirically, a period of credit growth when a country runs a current account deficit is more likely to lead to a crisis than the same credit growth when a country runs a current account surplus.

A current account deficit means the country is a net borrower from the rest of the world, and thus, this credit growth is financed with foreign borrowing. A current account surplus means the same growth in domestic credit is financed from domestic savings. Debt financed by domestic savings is more likely to roll over in bad times, and thus less likely to trigger a crisis.

Basically, Chinese households’ savings financed the nation’s ballooning corporate debt. As a result, the roll-over risk was comparatively low, and China’s corporate debt expansion would not raise the probability of a financial crisis as much as even a smaller credit bubble elsewhere might trigger a crisis in another country.

Chart 2 also shows that while China’s 2016 deleveraging campaign has been largely effective at restraining further growth of corporate leverage, government borrowing has driven the nation’s continued increase in overall debt levels. The debt level exceeded 300 percent of GDP as of June 2025, according to China’s National Bureau of Statistics.

Japan experienced debt run-up

There is a downside to the reduced risk that comes from domestically financed debt. Chinese capital controls mean savings are largely captive. Notably, Chinese authorities aggressively tightened capital outflow controls in 2016 when the country faced significant balance-of-payments stress.

Captive savings mean state-owned banks face little funding pressure. As loans come due, banks can easily roll over loans to unprofitable and otherwise insolvent companies to avoid recognizing loan losses on their balance sheets.

Such zombie lending was observed in Japan in the 1990s. Like China in the years after the Global Financial Crisis, Japan experienced massive growth in private sector credit in the 1980s.

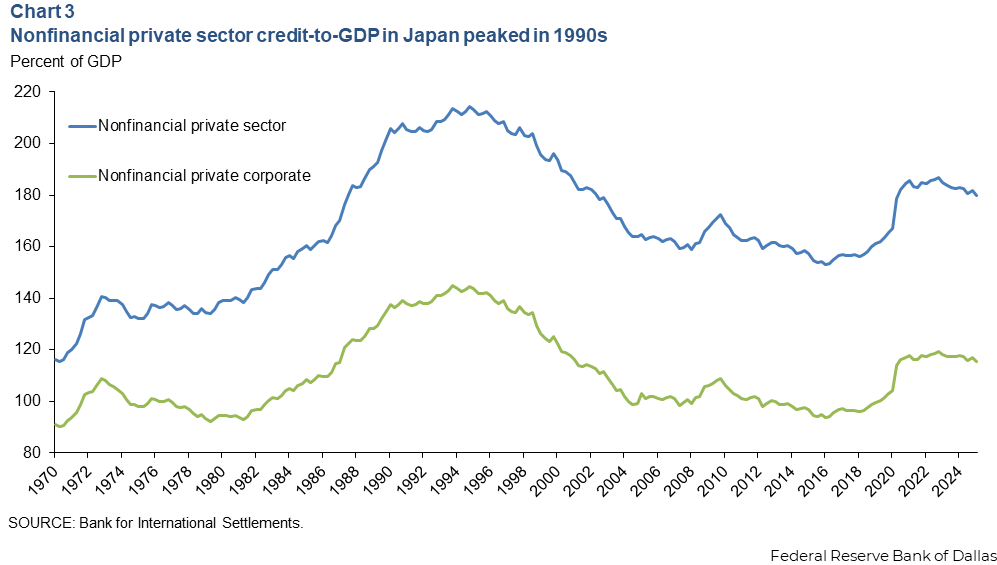

The ratio of nonfinancial private sector credit to GDP in Japan rose by 75 percentage points—from 139 percent to 214 percent—beginning at the end of 1979 to the peak in 1994 (Chart 3). About two-thirds of this credit growth was corporate, as the ratio of nonfinancial sector corporate credit to GDP rose by 50 percentage points, from 95 percent to 145 percent.

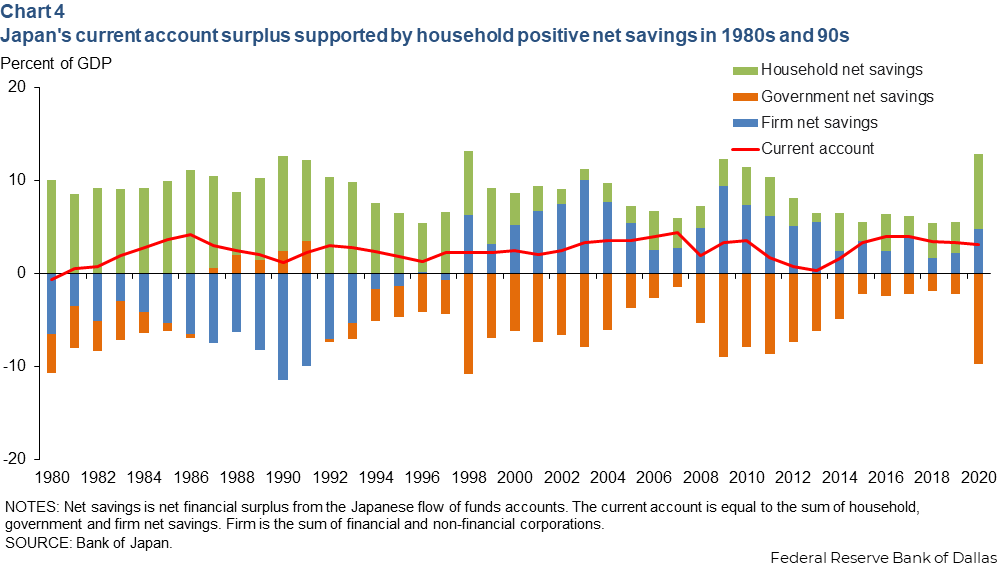

Like China, this Japanese credit growth was financed by household savings. Japan ran a current account surplus throughout this entire period, and negative net saving by firms was more than offset by positive net saving by households (Chart 4).

Economists Joe Peek and Eric Rosengren document the rise of zombie lending in Japan in the 1990s, as banks faced strong incentives to roll over the debt of otherwise insolvent firms in order to avoid recognizing loan losses. This process of evergreening would involve lending a firm just enough to make its interest payments.

Similarly, Ricardo J. Caballero, Takeo Hoshi and Anil K. Kashyap detail how this zombie lending depresses the usual process of creative destruction (allowing firms to fail so that new, healthier ones may arise) and results in too much capital tied up in otherwise insolvent firms. The net result is low investment and productivity growth for the economy as a whole.

Caballero, Hoshi and Kashyap use firm-level financial data to classify Japanese firms as zombie or not, depending on whether they received subsidized credit. With this, the researchers show zombie firm share of firm assets in a given industry. Thus, the share of assets among all non-financial firms in Japan held by zombie firms rose from 3 percent in 1991 to 16 percent in 1996.

The zombie share varied across sectors and was more pronounced in non-traded sectors shielded from foreign competition (unlike traded sectors that were not). The share of assets held by zombie firms rose from 2 percent to 12 percent in the manufacturing sector but jumped from 5 percent to 33 percent in the real estate sector and from 11 percent to 39 percent in the services sector.

Similar pattern emerges for China’s zombie firms

The Japanese experience shows that zombie lending can result in capital tied up in insolvent and unproductive firms. There is mounting evidence that a similar effect has appeared in China, with important implications for China’s future growth, efficiency of capital allocation and productivity.

Using firm-level financial data for Chinese firms, we can calculate zombie shares for Chinese sectors. We classify a firm as a zombie in a given year if its EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization, also known as operating earnings) is less than its interest expense. That is, a firm is a zombie if it does not earn enough from operations to meet interest expenses. The firm would be insolvent if not for continued funding from banks.

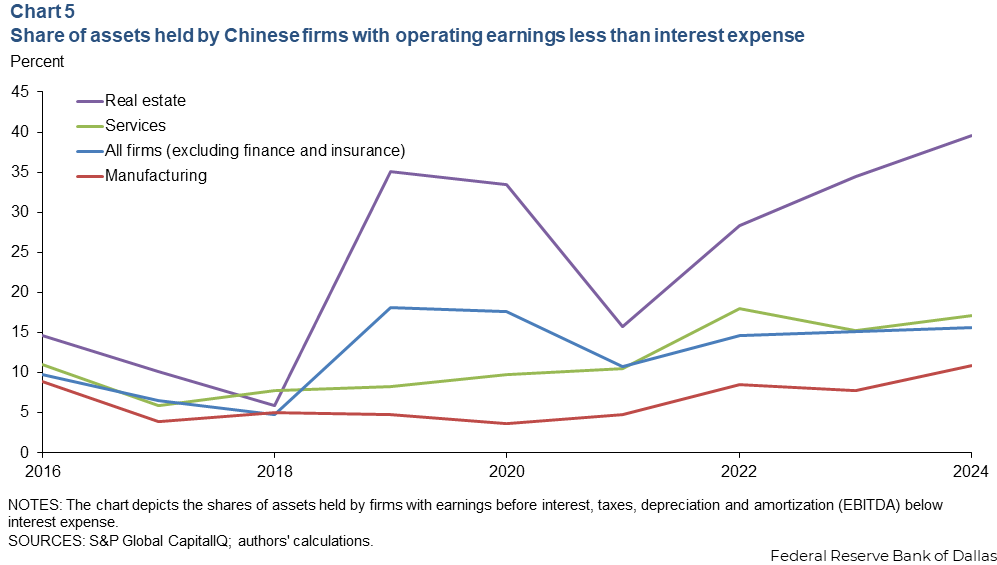

The share of assets for all Chinese non-financial firms held by zombie firms rose from 5 percent to 16 percent from 2018 to 2024 (Chart 5). The real estate sector has by far the highest zombie share, rising from 6 percent to 40 percent, consistent with China’s extended property sector downturn.

The zombie share in manufacturing has risen fairly rapidly from a low of 4 percent in 2020 to 11 percent in 2024. With a sustained decline in industrial profits, this share looks likely to continue growing. Yet, China’s services sector has a higher proportion of zombie firms, increasing over the past several years to 17 percent in 2024.

China’s current overcapacity, falling prices and increasing corporate losses in the manufacturing sector has been dubbed involution, disorderly price competition that damages industry health. Chinese authorities have announced a high-profile anti-involution campaign in 10 leading manufacturing sectors. The success of this effort will be important in limiting the share of zombie assets in the manufacturing sector.

Yet, the higher zombie share in services may be equally important at a time when authorities pursue tentative efforts to rebalance the economy in favor of consumption and services. While policies include some direct support to households, a key focus appears to be boosting investment in services, including through subsidized loans.

A 2024 International Monetary Fund analysis highlights China as maintaining some of the most restrictive services sector policies among major economies. The rules seek to limit competition from foreign firms and, in many cases, from domestic Chinese private enterprises. The Japanese experience shows that when there are few constraints on rolling over bad loans, the inefficient allocation of capital can lead to decreased productivity, especially in sectors shielded from foreign competition.

About the authors