How AI debt financing impacts duration supply and interest rates

Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) promises to be a transformative technology with the potential to reshape the labor market and the economy. Its capabilities and impacts have been the subject of much study and debate, including by several of our colleagues at the Dallas Fed (see here and here). Growth in its capabilities and adoption has driven capital expenditure for several years. But from the somewhat narrower perspective of U.S. fixed income markets, AI has only recently burst forth onto the stage.

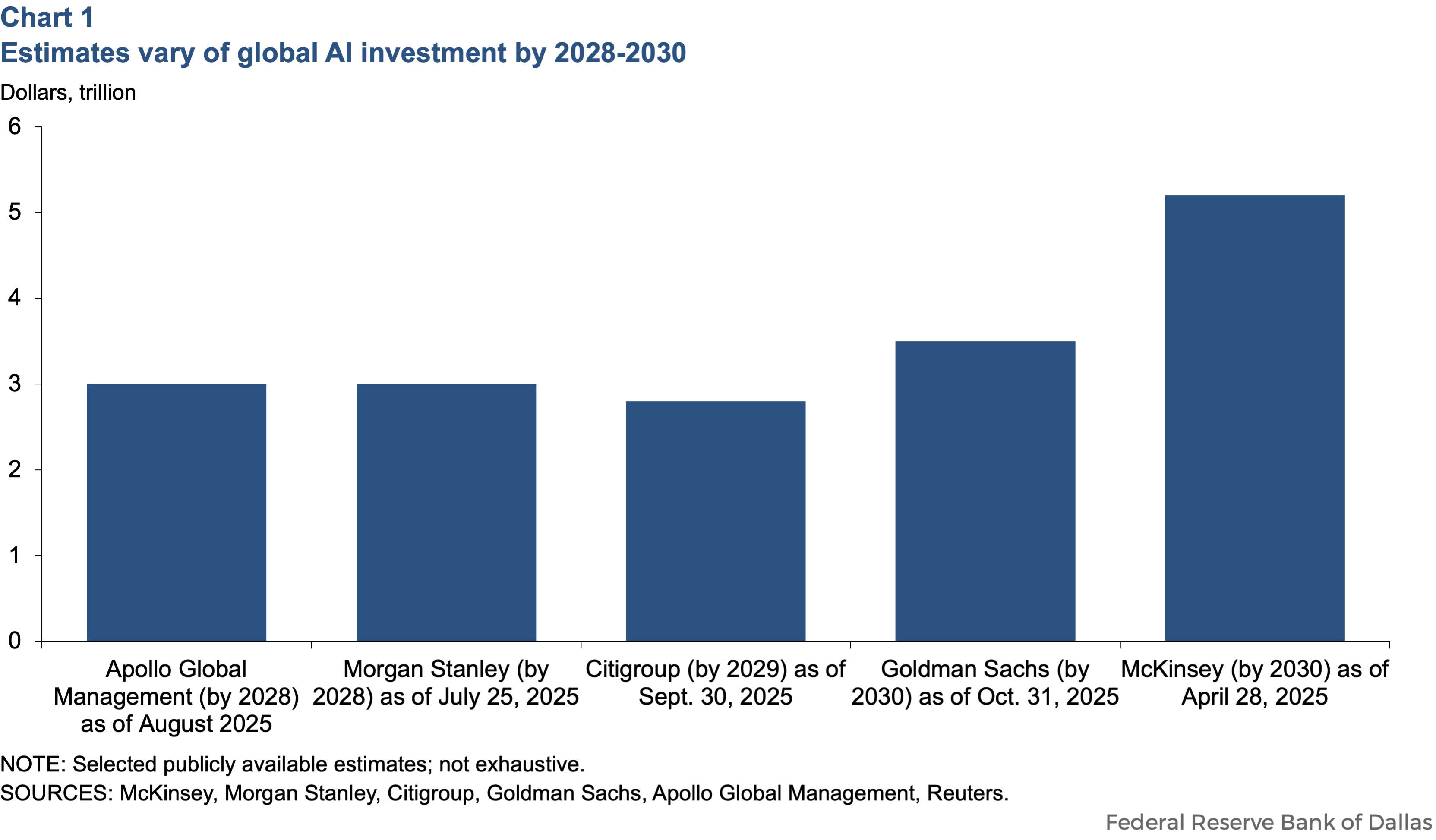

It is generally accepted that the scale of investment in data centers with the computational capacity to deliver AI technologies to end users is extremely large. Several different estimates place this number between $3 trillion and $5 trillion over the next three to five years (Chart 1). While a significant portion of the initial investment (estimated by various equity analysts and industry watchers to be around $500 billion to $600 billion to date since 2023) appears to have been internally funded by hyperscalers[1] from retained earnings, these firms have begun turning more recently to public and private debt markets. Issuance from these firms and others participating in the AI buildout has been both large and long in duration. Financing transactions in private markets are less observable, but several examples of structured off-balance-sheet borrowing from private lenders have been reported in the financial press.

Data center financing will supply duration through multiple channels

The financing of AI-related data centers promises to supply significant duration into fixed income markets through a combination of direct effects, duration risk transfers via swap activity and displacement effects. The supply through these channels carries with it implications for the yield curve slope and level of term premium.

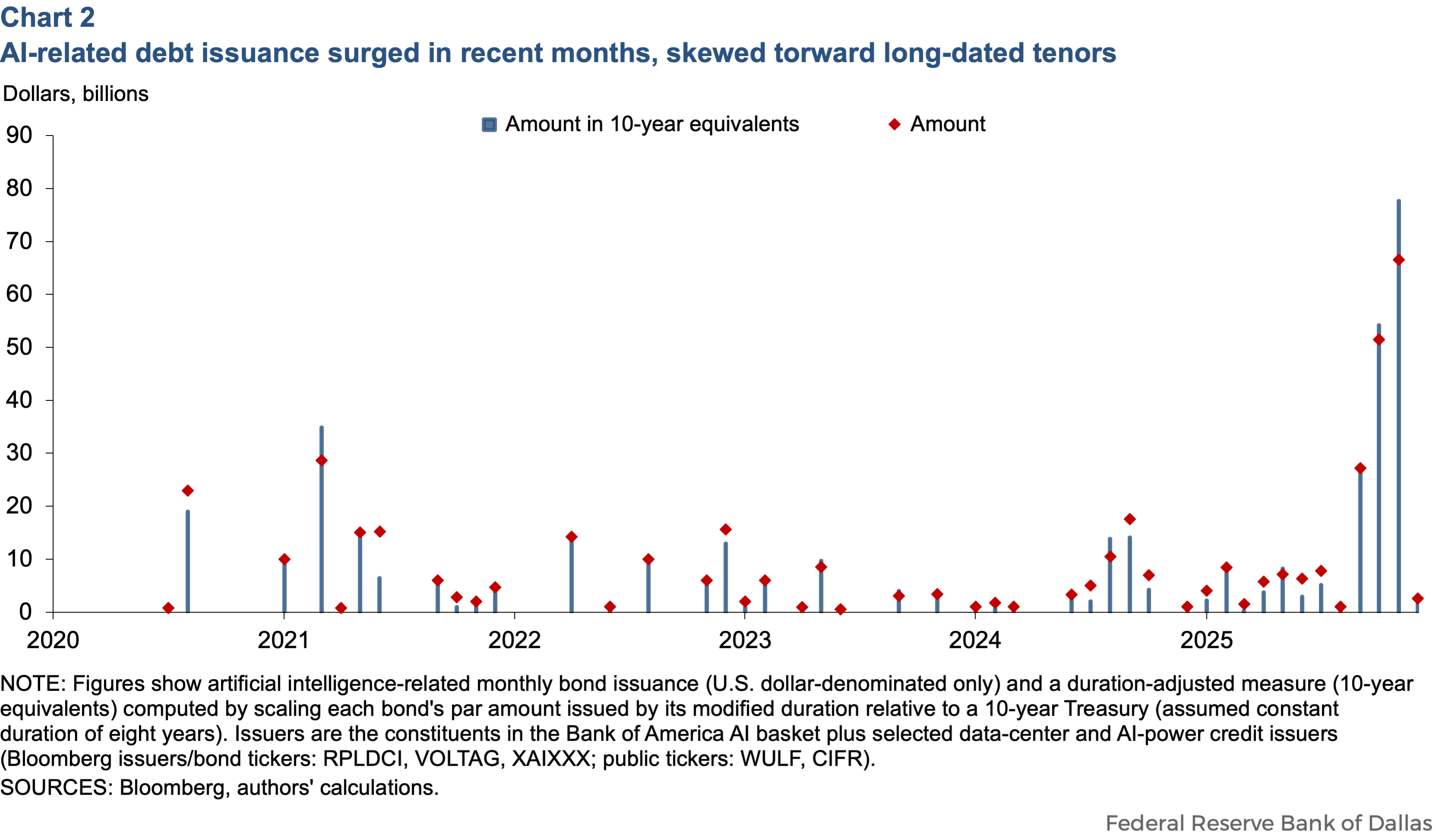

Direct effects: If recent issuance in investment-grade markets is an indication of things to come, corporate bond issuance related to AI investments could become a significant source of duration supply in U.S. fixed income markets. As Chart 2 shows, recent issuance from AI-related firms has been both large and concentrated in long maturities. The long duration of such issuance likely reflects the fact that the underlying assets being financed are long-lived, with underlying economics that do not vary with interest rates over the course of a business cycle. As a result, fixed-rate liabilities would be preferred by the borrower in order to lower income volatility. Wall Street estimates of AI-related investment grade issuance vary somewhat but are centered on $300 billion for this year, which could result in new duration supply of as much as $360 billion in 10-year equivalents over the course of 2026, or about an eighth of the duration supply from U.S. Treasury issuance.

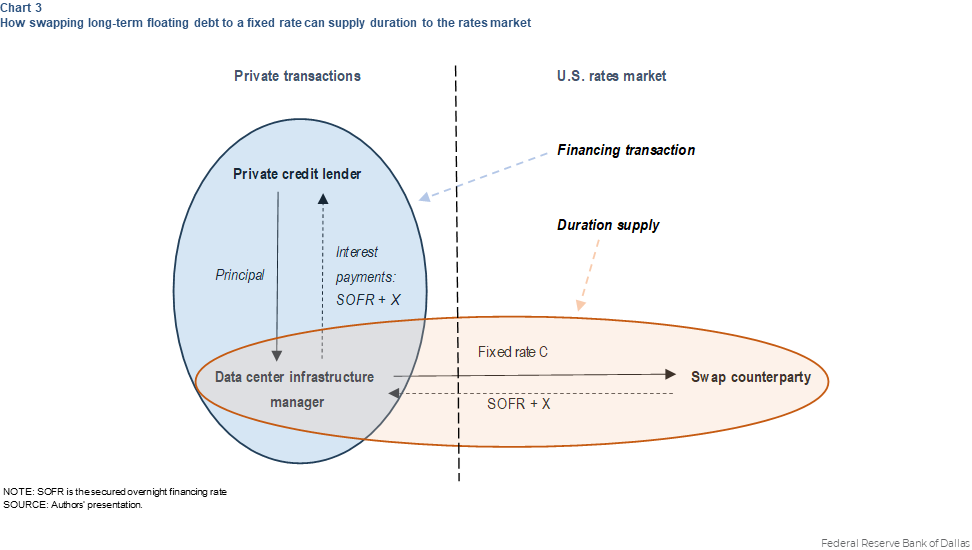

Synthetic duration supply: Data center owners and operators are likely to seek fixed-rate financing for long terms, given the long lives of their assets.[2] While issuance in corporate bond markets can readily accommodate those needs, borrowing from other sources (e.g., private credit markets) is much more likely to be floating-rate, because of the risk preference of investors in those markets. This means that data center managers are likely to pair borrowings in such transactions with pay-fixed swaps to synthetically transform those liabilities into fixed-rate term loans. A stylized illustration of how this works is shown in Chart 3.

Such pay-fixed swaps would effectively represent a form of synthetic duration supply to the rates markets. Anecdotal evidence from market participants suggests that this may have been sizeable in the fourth quarter of 2025, possibly totaling as much as $50 billion in 10-year equivalents of bond issuance or more. Much like actual issuance of long duration Treasuries, this kind of supply should on the margin bias yield levels higher and the yield curve steeper. But unlike actual Treasury market duration supply (which would, ceteris paribus, cheapen Treasuries relative to swaps), this synthetic duration supply should bias Treasuries richer versus swaps, since it ought to pressure swap yields higher relative to Treasury yields. This subtle difference in how synthetic duration supply impacts swap spreads vis-a-vis Treasury supply suggests a potential empirical approach to inferring the existence and scale of such transactions.

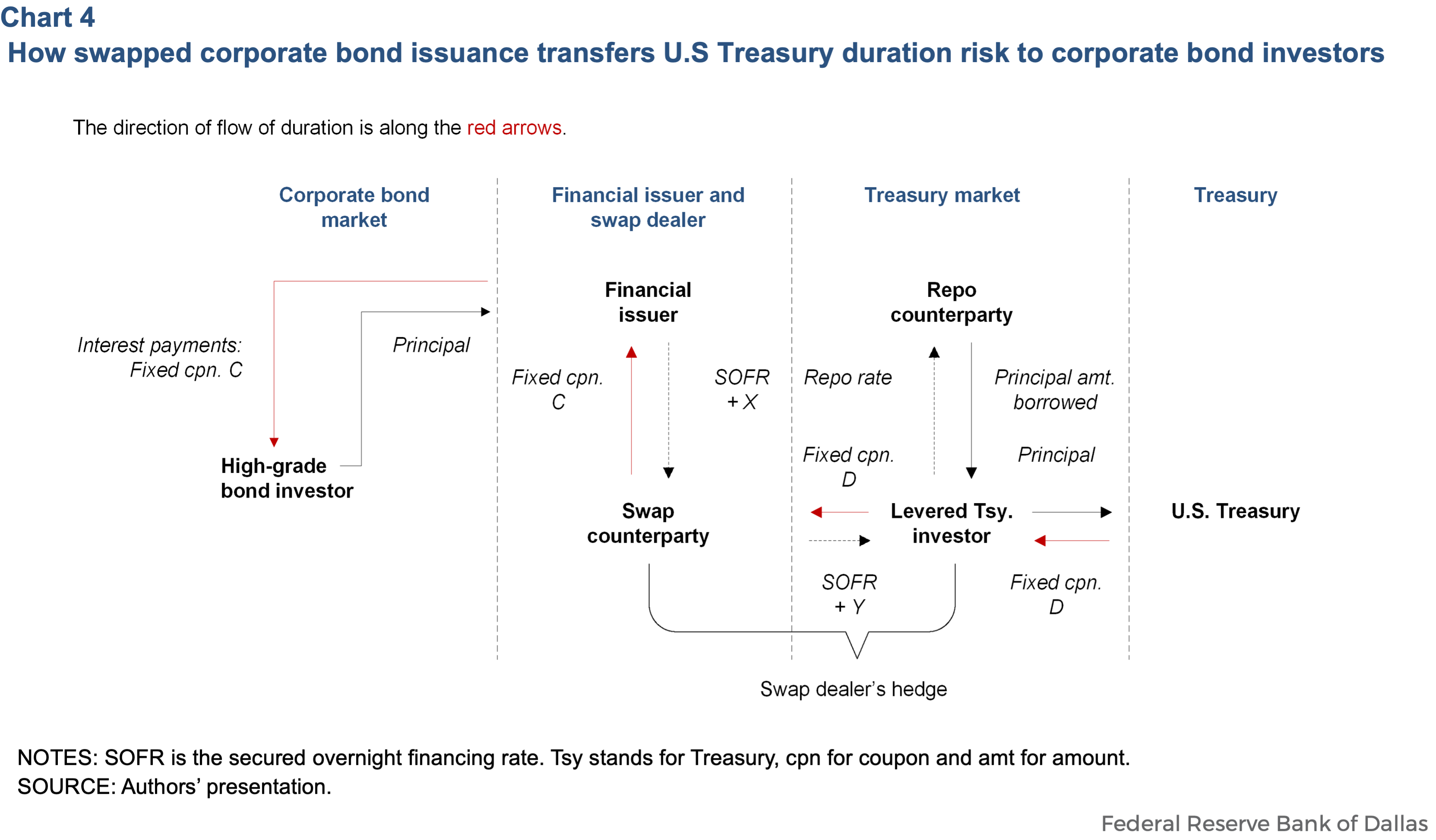

Substitution effects: It is conceivable that hyperscalers’ issuance will partly crowd out supply from other investment grade issuers, including financial firms that are currently the dominant issuers in the investment grade market.[3] Should this occur, the mere substitution of technology issuance for financials (holding overall quantity of supply constant) would effectively translate into incremental duration supply (or more precisely, incremental negative duration demand) to the market as a whole and for the Treasury market in particular. This is because of a somewhat under-appreciated side effect of swapped issuance by financial firms, which effectuates the transfer of duration risk from the U.S. Treasury to corporate bond investors. Financial firms tend to prefer floating-rate liabilities. Therefore, they typically transform their corporate bond issuance into floating-rate liabilities by pairing the bonds with receive-fixed swaps. In doing so, they are effectively buying duration offsets from swap dealers, who in turn buy duration from levered Treasury investors holding asset-swapped Treasuries. The net effect is that financial issuance results in corporate bond investors buying duration from the Treasury market while providing funding to financial firms. A stylized schematic of the flow of duration in such transactions is shown in Chart 4.

How AI financing impacts the rates markets

The emergence of duration supply related to the financing of AI infrastructure is a recent development. But a nuanced look at the rates market already shows signs of such supply. To identify this impact, we make use of the observation that a pickup in duration supply ought to steepen the long end of the curve regardless of whether such supply comes in Treasuries or in credit markets, but the impact on Treasury asset-swap spreads would differ based on the source. Duration supply in the form of Treasuries might be expected to cheapen Treasuries versus swaps, while the supply effects we have discussed in this note ought to richen Treasuries relative to swaps.

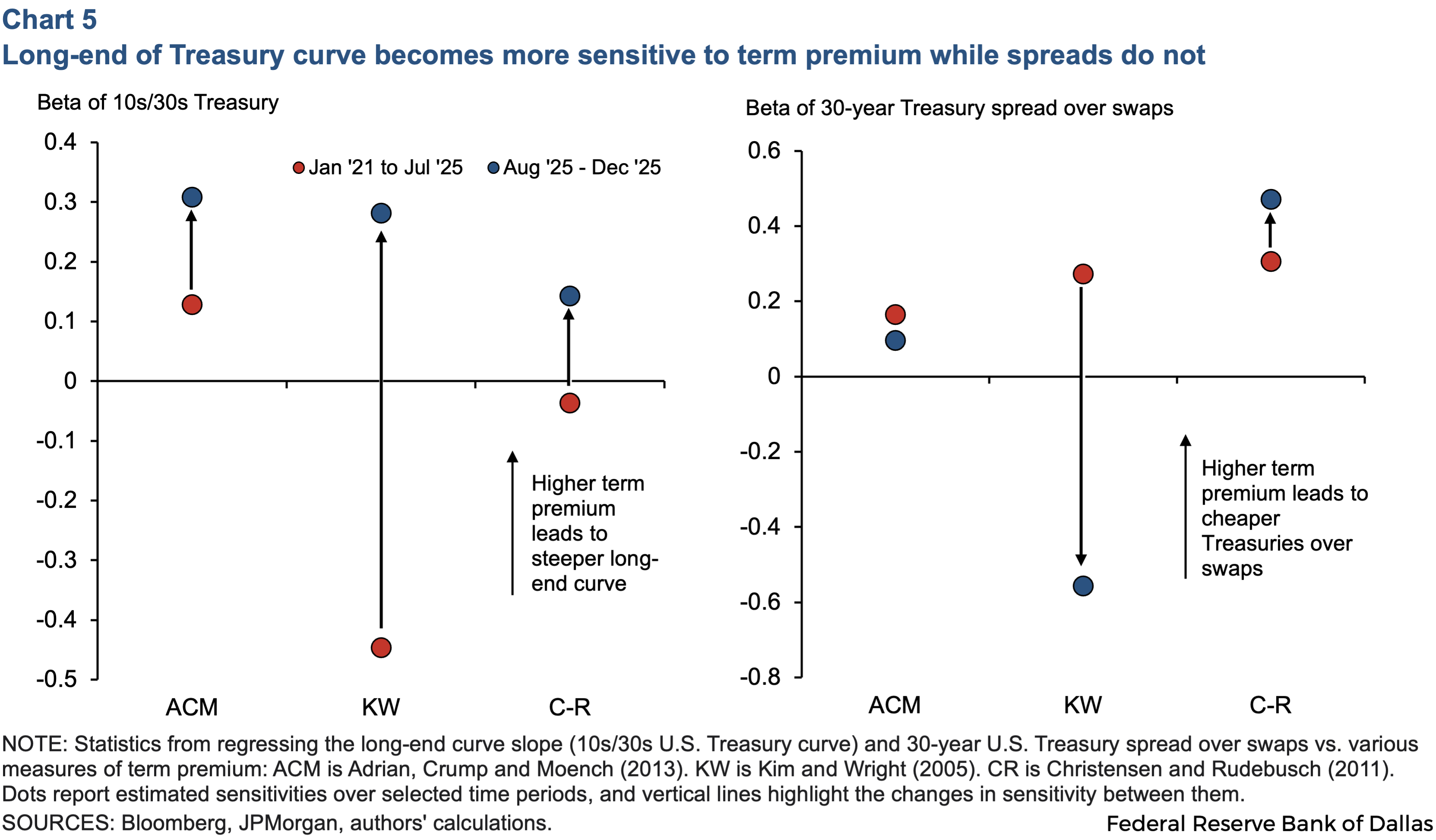

One way to look for evidence of AI-driven duration supply is by searching for an emerging divergence between the response of curve slopes and swap spreads in longer maturity sectors to term premium. We do this in Chart 5 by measuring the sensitivity of the 10-year-to-30-year Treasury curve slope to 10-year term premiums as well as the sensitivity of 30-year Treasury yield spread over swap rates to 10-year term premiums.[4] As seen in the chart, the 10-year-to-30-year yield curve slope has become increasingly sensitive to three different measures of 10-year term premium, suggesting a growing role for long-end duration supply. At the same time, the sensitivity of 30-year asset swap spreads to term premium declined for two of the three measures while rising modestly for the third. Taken together, this is indicative of a divergence between the response of the yield curve slope and swap spreads at the long end, which is exactly what might be expected in the presence of synthetic duration supply from AI financing.

Conclusions

Despite the relatively large scale of corporate debt markets, the Treasury market has historically been where the bulk of interest rate duration risk is supplied and traded. Although this will remain the case for the foreseeable future, data center financing looks likely to deliver significant additional duration risk to the rates market through a combination of direct bond issuance, swap transactions to lengthen the duration of floating-rate borrowings, and the potential displacement of financial issuers who typically buy duration offsets against their own debt issuance. The growing significance of these channels could weaken long-standing empirical relationships between the long-end Treasury curve slope and long-maturity swap spreads that persisted during long historical periods when duration supply came mainly through Treasuries. A divergence between long-end swap spreads and curve slopes is indicative of such non-Treasury duration supply effects, which observers must account for when attempting to attribute long-end curve and swap spread moves to fiscal, monetary and regulatory policy drivers.

Notes

- The term “hyperscalers” has become commonly used to refer collectively to large technology and cloud infrastructure firms such as Google, Microsoft, Open AI, Meta, Amazon, Oracle and Apple.

- AI data center investments are estimated to involve a blend of very long-lived assets such as physical infrastructure and equipment, which are commonly depreciated over 10 to 15 years or more, and investments in semiconductors, which are being depreciated over five to six years by major technology firms according to media reports and Securities and Exchange Commission filings.

- Financial issuers accounted for about 38 percent of all investment-grade supply in 2025.

- Since yield curve slopes and asset-swap spreads of Treasuries may be impacted by several factors, a direct comparison may not help identify supply effects. However, since duration supply is likely to impact term premium regardless of channel, examining the sensitivity of yield curve slope as well as Treasury yield spread over swaps to term premium is a way to examine how duration supply may be differently impacting these two market variables. Moreover, since there are many different measures of term premium, we apply our framework to three commonly used measures. These measures of term premium are all focused on the 10-year sector.

- Will AI replace your job? Perhaps not in the next decade. Mark Wynne and Lillian Derr, Dallas Fed Economics, June 2025.

- Advances in AI will boost productivity, living standards over time. Mark Wynne and Lillian Derr, Dallas Fed Economics, June 2025.

- Adrian, T., Crump, R. K., and Moench, E. (2013). Pricing the term structure with linear regressions. Journal of Financial Economics, 110(1), 110–138.

- Kim, D. H., and Wright, J. H. (2005). An Arbitrage-Free Three-Factor Term Structure Model and the Recent Behavior of Long-Term Yields and Distant-Horizon Forward Rates. Finance and Economics Discussion Series, 2005.0(33), 1–21.

- Christensen, J.H.E., Diebold, F.X. and Rudebusch, G.D. 2011, The affine arbitrage-free class of Nelson–Siegel term structure models, Journal of Econometrics, vol. 164, no. 1, Elsevier B.V., pp. 4–20.

About the authors