Electric reliability concerns spur Texas backup generation boom

Amid growing concerns about reliability of electricity services across power-hungry Texas, deployment of back-up power sources—microgrids and alternative generation—is increasing. These assets, serving customers ranging from college campuses to oilfield operations, help keep the lights on when disaster strikes.

After a spate of outages that plunged millions into the dark, Texans can’t help but think about how to keep the lights on.

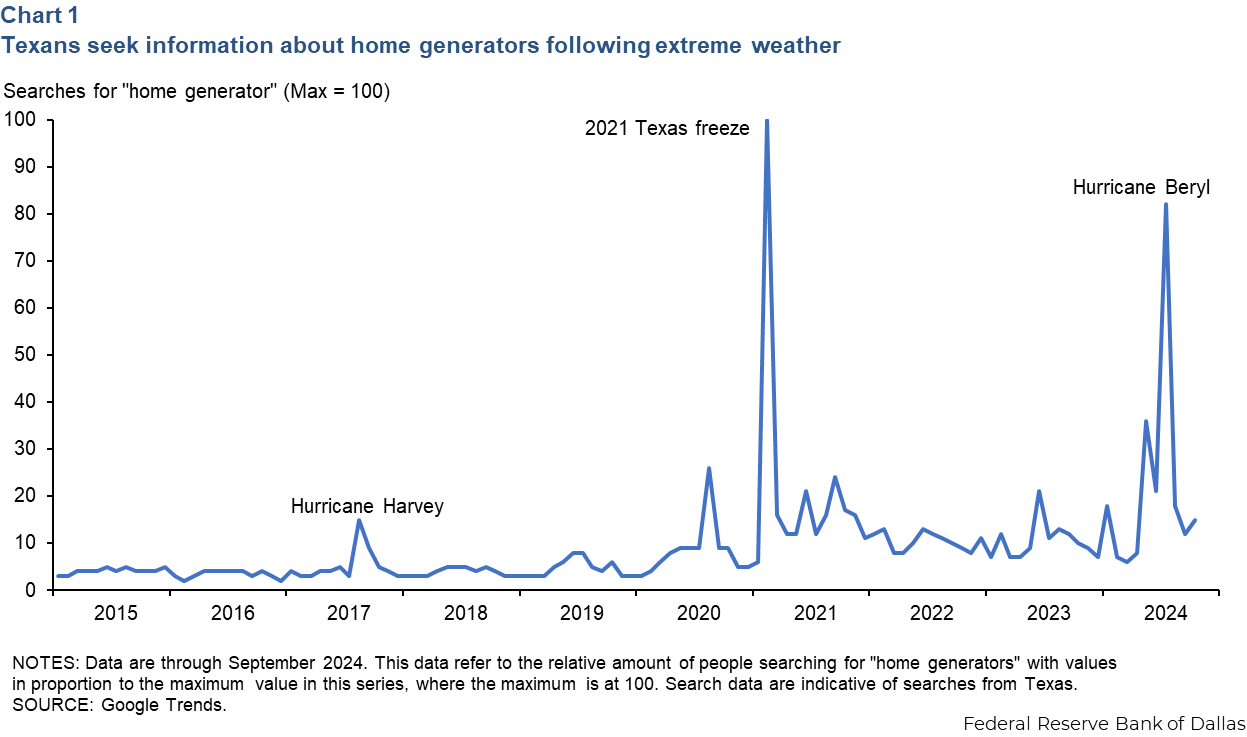

The deadly, statewide deep freeze outage in February 2021, affecting 4.5 million customers, was perhaps the most notable electricity delivery failure. Most recently, Hurricane Beryl put 2.7 million southeast Texas customers offline in July, just weeks after straight-line winds knocked out customers from North Texas southward to the Gulf Coast.

Extreme weather events in Texas aren’t one offs. The largest state in the Lower 48 often runs the gamut of weather risks—tornadoes, derechos, floods, hurricanes and extreme heat and cold. The state recorded 210 outages in 2000–23, the most in the country, often at significant expense to power providers and to customers. The 2021 deep freeze cost $4.3 billion in initial expenses, while the 2024 wind events totaled an estimated $1.8 billion.

Weather events are revealing these vulnerabilities at a time of economic growth, much of it drawing on already strained electric power sources, including new data centers, semiconductor manufacturing facilities and oilfield electrification.

Some Texas households and businesses have opted to invest in their own backup generation. Others have taken the next step: investing in private microgrids to ensure their energy needs are consistently met. Grocer H-E-B and retailer Buc-ee’s are among the most visible such investors, while the University of Texas at Austin houses the largest non-military microgrid, with a capacity of 146 megawatts.

As the name implies, a microgrid is a miniature electric grid, complete with interconnected loads, generators and sometimes even energy storage systems. Unlike a backup generator, a microgrid can be autonomous from the electric grid for most or even all of the time. Take-up of microgrids has been notable among Texas commercial entities.

Meanwhile, the Legislature, the Public Utility Commission of Texas and the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT), the agency charged with operating the electric grid servicing most Texas customers, have weighed in on the system’s challenges. Remediation measures include overseeing power plant weatherization, financing new generation, and hardening transmission infrastructure.

Extreme weather drives attention to backups

Google Trends data indicate that interest in home generators peaks following extreme weather events (Chart 1).

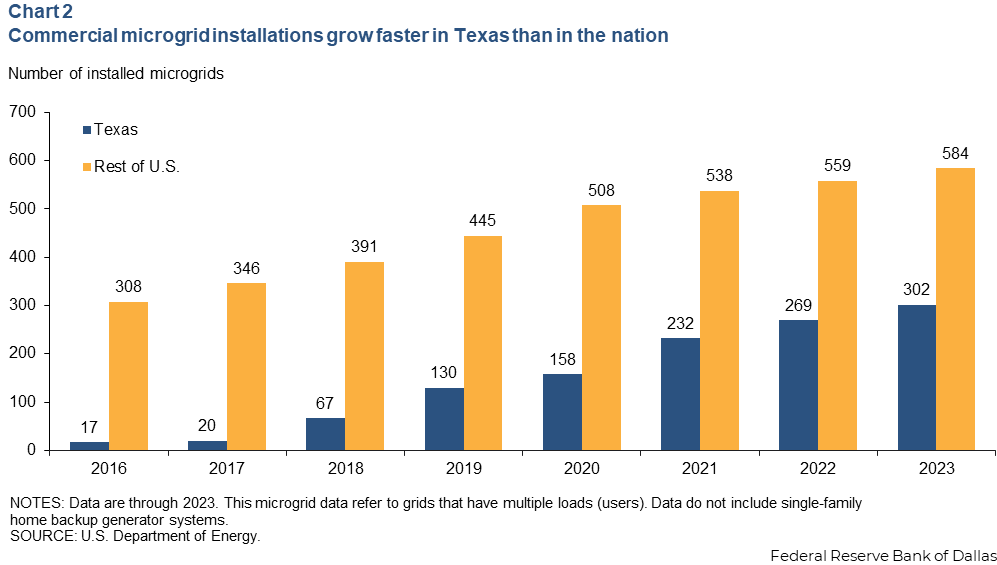

While the data on single-family backup generators in Texas are imprecise, the Department of Energy and consulting firm ICF International assembled a map of U.S. microgrids. The microgrids they identify are defined by distinct networks of energy resources and energy consumers that can be connected and disconnected at will from the larger utility grids. Backup generators are explicitly excluded if they are not used day-to-day.

Commercial microgrid operations in Texas have accelerated since 2017, when Hurricane Harvey devastated the upper Texas Gulf Coast, including much of Houston (Chart 2). The storm notably swamped communities and operations to the east, including refining and petrochemical complexes. Harvey came a dozen years after Hurricane Katrina disabled New Orleans and put the city under water.

Houston, Corpus Christi, Katy, Spring and San Antonio account for more than half of the microgrids in Texas and are the top five-ranked cities by number of microgrids in the state. Three of these cities are within the Houston metropolitan area, especially affected by hurricane and tropical storm activity.

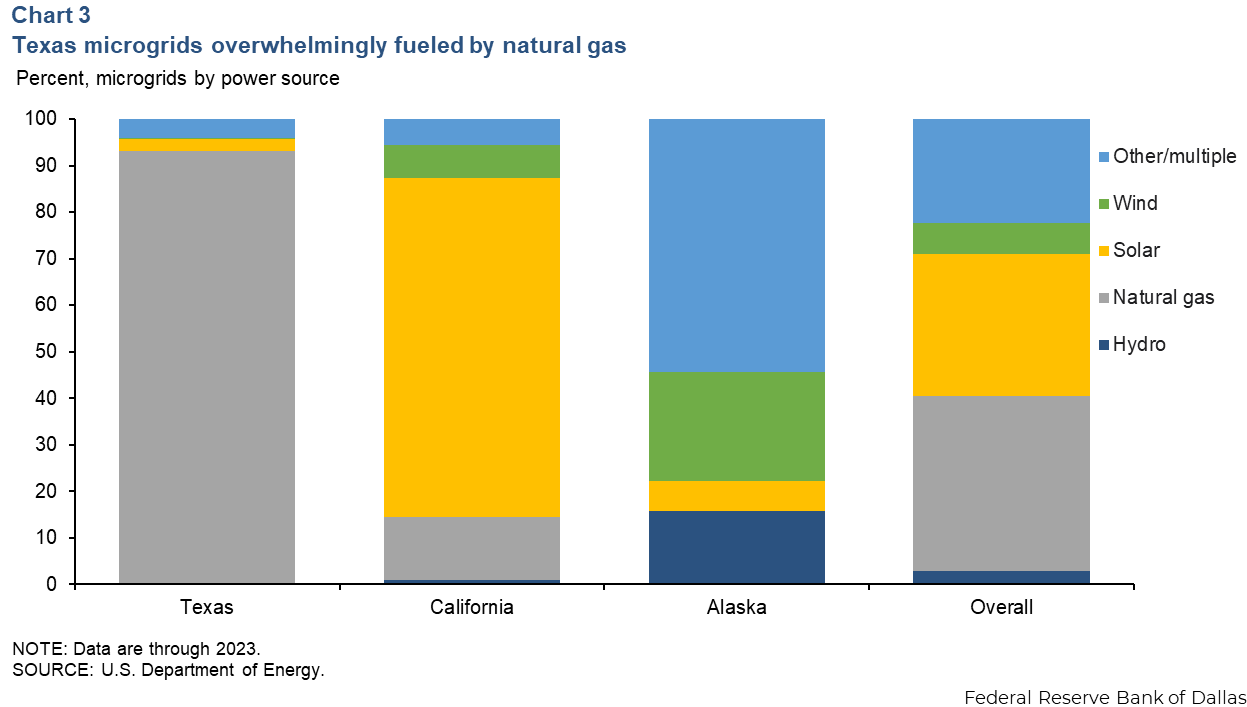

Fossil fuels power the vast majority of microgrids in Texas, far more than in California or Alaska, the states with the second- and third-most microgrids (Chart 3). The cheap and abundant availability of natural gas in Texas makes these microgrids easier to supply, install and sell.

Microgrids provide reassurance to industries especially sensitive to disruptions. Financially, the Texas semiconductor industry was particularly hit hard by the 2021 freeze. NXP, a Dutch chip manufacturer that supplies the automotive industry from an Austin plant, estimated the weather event cost it $100 million in lost revenue. Another Austin-area semiconductor plant, this one belonging to Samsung, closed for more than a month, with the company subsequently settling with its insurer for $400 million in damages.

Data centers, the backbone of artificial intelligence technology as well as big data computational work, are a growing industry in Texas and vulnerable to power outages. An industry trade group, Uptime Institute, estimated 25 percent of data center outages in 2022 resulted in a per-incident cost of at least $1 million..

Texas businesses pursue microgrids to meet growth

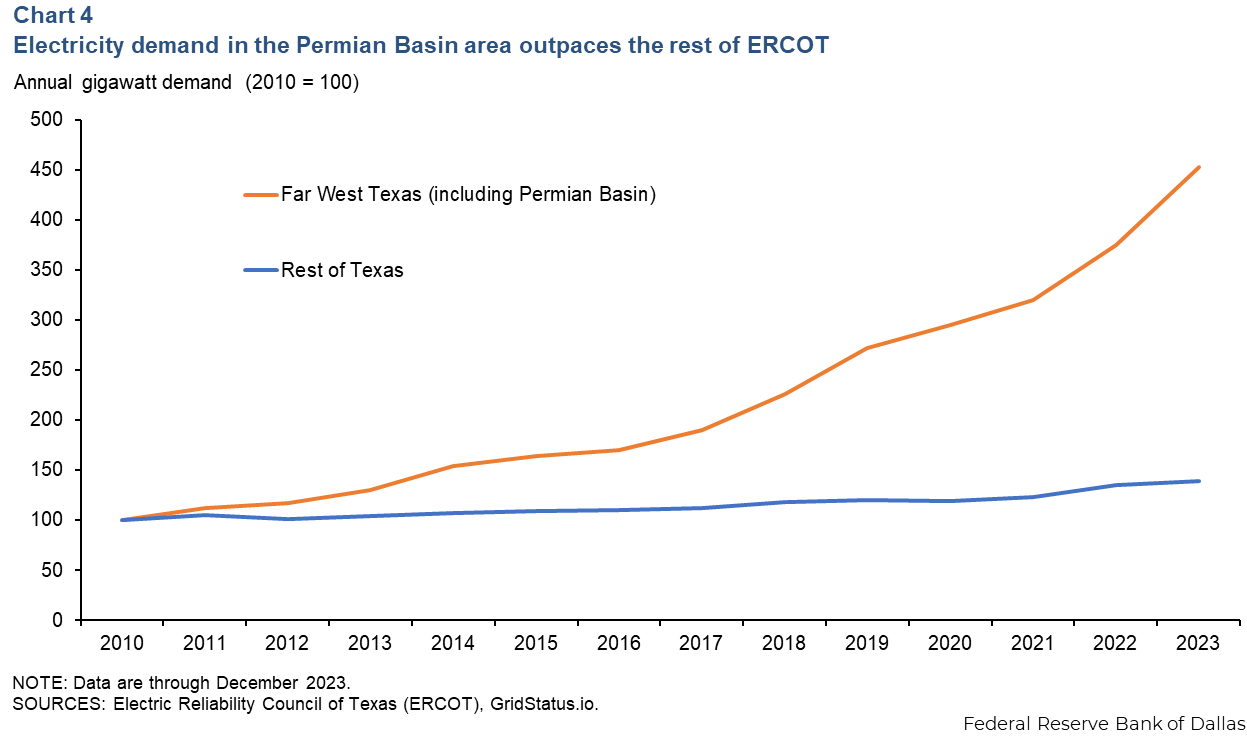

Electricity demand is growing, though more in some areas than others. The rate of growth for power demand in the Permian Basin region has been greater than in other ERCOT service areas since 2010 (Chart 4).

This growth is projected to continue and likely expand. S&P Global estimated in a March 2023 report prepared for ERCOT that Permian Basin electricity demand will grow from 4.2 gigawatts in 2022 to 17.2 gigawatts by 2032.

Much of the new load is driven by oil and gas electrification, as companies attempt to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and meet investors’ environmental, social and governance expectations. This can include the electrification of upstream and midstream operations. For upstream operations, fracking equipment, drilling rigs and related machinery can be electrified. ERCOT expects midstream operations, pipelines and processing facilities to be 20 percent electrified by 2027, double the share in 2020.

Many energy companies have recently expressed interest in electrifying their operations. Responding to the September 2024 Dallas Fed Energy Survey, 16 percent of executives said they have already electrified their operations, with an additional 33 percent saying they intend to do so in the coming years.

This growth needs new infrastructure, which generation, transmission and distribution developers are not on track to meet. S&P Global in its report said planned infrastructure spending would be inadequate to cover even half of the increased load growth.

Among the 46 percent of Dallas Fed Energy Survey respondents who said their firms had electrified sites in the Permian Basin, primary concerns were “uncertainty about future access to the grid” or “uncertainty about future grid stability.” There was less worry about expense, lead times for equipment and regulatory/permitting issues.

These compounding factors have incentivized some in the Permian Basin to invest in microgrids. In a 2024 survey of oil and gas companies by wholesale power provider NextEra Energy, 35 percent of respondents said they had implemented microgrids, scaling from a single site to an entire substation’s worth of grid support. An additional 50 percent of respondents reported their companies are considering installing microgrids.

In addition to the energy sector, data centers are prime candidates for microgrid adoption. Texas had nine data centers in 2019. The Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts reported 57 registered data centers as of August 2024, including 40 built after 2022. In order to register and connect to the ERCOT grid, these centers must obtain interconnection permits, a process requiring an average of 3.5 years.

As a work-around, some data centers have considered behind-the-meter options, which include building out private electricity infrastructure. One example is through co-location, which connects data centers to reliable power sources through microgrids. This can bypass the immediate need for interconnection and save waiting time.

In Texas, Digital Power Optimization, a data center operator and cryptocurrency miner, announced plans in January 2024 to develop up to 100 megawatts of wind generation behind the meter with Schneider Electric, a French multinational specializing in energy management.

Consumers consider trade-offs between resilience, costs

Backup generation and microgrids provide Texans resilience, but at a price.

The construction of microgrids costs $2 million to $5 million per megawatt in 2018 dollars, depending on the energy source used, according to a National Renewable Energy Laboratory study in 2022. (The U.S. Department of Energy operates the National Energy Laboratory.) By comparison, the capital costs for utility-scale solar, solar with batteries, wind and combined-cycle natural gas plants all fall below $2 million per megawatt in 2018 dollars, the Energy Information Administration reported in 2022.

Constructing microgrids may provide resilience for end users but expanding the grid for more large-scale power generation is economically more efficient. While some energy generated by a central power plant is lost in transmission during extreme weather, grid-scale plants remain more efficient and cost-effective per megawatt-hour than smaller, on-site generators.

The Legislature has taken steps to address cost barriers for microgrid operations, particularly involving small, 1- to 2.5-megawatt projects deemed key. These serve electricity users that provide a benefit to the public but lack access to financing for the millions of dollars that microgrids cost. Examples include assisted living centers, grocery stores and gas stations. Lawmakers allocated $1.8 billion for grants in 2023 to support this segment of potential microgrid users.

Other costs are less about funding and more about the environment. The state’s abundant and accessible natural gas resources that are frequently utilized for backup generation, and microgrids are less environmentally friendly than relying on ERCOT, which is roughly one-third renewable energy.

Backup generation isn’t the only option to bolster reliability. Hardening power infrastructure—reinforcing transmission and distribution equipment—can improve dependability. For hurricane-prone Gulf of Mexico areas, hardening even 1 percent of power lines can reduce hurricane outage probability by a factor of five, a paper in Nature Energy from German researchers concludes.

As the state works to develop infrastructure to keep pace with Texas’ rapid growth, increasingly frequent extreme weather events will likely complicate efforts. Thus, despite the cost, demand for alternatives and safeguards that microgrids and other backup sources provide will likely become more pronounced.