Mexican peso strength noteworthy among emerging markets during Fed tightening

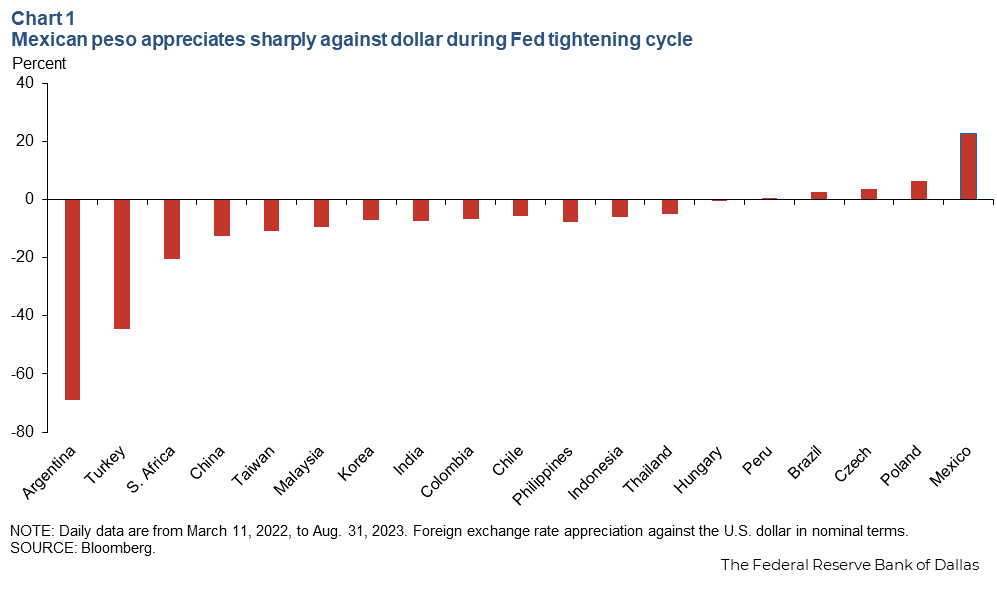

Many emerging-market currencies have depreciated modestly during the Federal Reserve’s tightening cycle that began in March 2022. The Mexican peso, however, has outperformed the group during the period, appreciating around 20 percent against the dollar (Chart 1).

The unusual strength of the peso, which makes up 13.8 percent of the Fed’s trade-weighted dollar index, can be attributed to short-run factors such as high interest rate differentials relative to the U.S. and investor positioning, as well as longer-run macroeconomic fundamentals.

The currency’s performance is particularly noteworthy because of the significant role Mexico plays in the Texas and U.S. economies. Data suggest Mexico is on track to surpass China as the top U.S. trading partner this year.

Proactive interest rate increases boost peso attractiveness

An important determinant of a currency’s attractiveness is the interest rate (or yield) associated with that currency relative to an alternative currency. Exchange rate fluctuations also impact investor returns. For example, if currency A has a higher yield than currency B, and if the exchange rate between currency A and B is not expected to fluctuate much, investors will find currency A more attractive, all else equal.

An investor can capture the interest rate differentials across countries by borrowing funds from the country where interest rates are lower and lending in a higher-yielding currency of a second country, or by simply using derivative instruments such as futures and foreign exchange swaps. This popular trading strategy is called a “carry trade.”

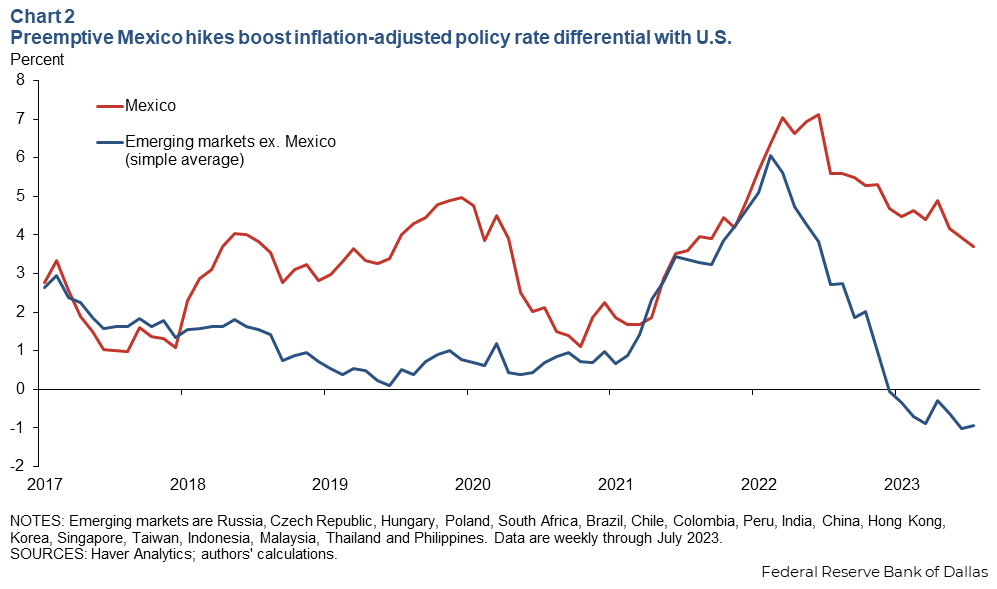

The real (inflation-adjusted) policy rate differential between Mexico and the U.S. widened notably in 2021, when Banco de México raised its policy rate, initiating monetary policy tightening almost a full year before the Fed started its tightening cycle (Chart 2).

Mexico’s central bank cumulatively increased its policy rate 7.25 percentage points, exceeding the Fed’s 5.25-percentage-point rise. At the widest differential between the two, in late 2022, a carry trade investor could earn around 7 percentage points in real return, assuming the dollar-peso exchange rate remained stable, by borrowing funds in U.S. dollars (paying U.S. interest rates) and lending in Mexican pesos (earning peso interest rates). Although narrowing from its peak, the differential remains elevated, at around 4 percentage points.

Mexico compares favorably with many emerging-market currencies on the perceived tradeoff between risk and carry. Mexico’s interest rates are meaningfully higher than lower-risk Asian economies, while Mexico’s macroeconomic policy mix is perceived as more stable than many high-yielding emerging-market Latin American counterparts.

Additionally, the peso is the third-most-traded currency among developing countries (after the Chinese renminbi and Indian rupee). Analysts note that in the recent period, the peso’s liquidity has, on the margin, supported its attractiveness as a carry-trade currency.

Fiscal discipline yields dividends

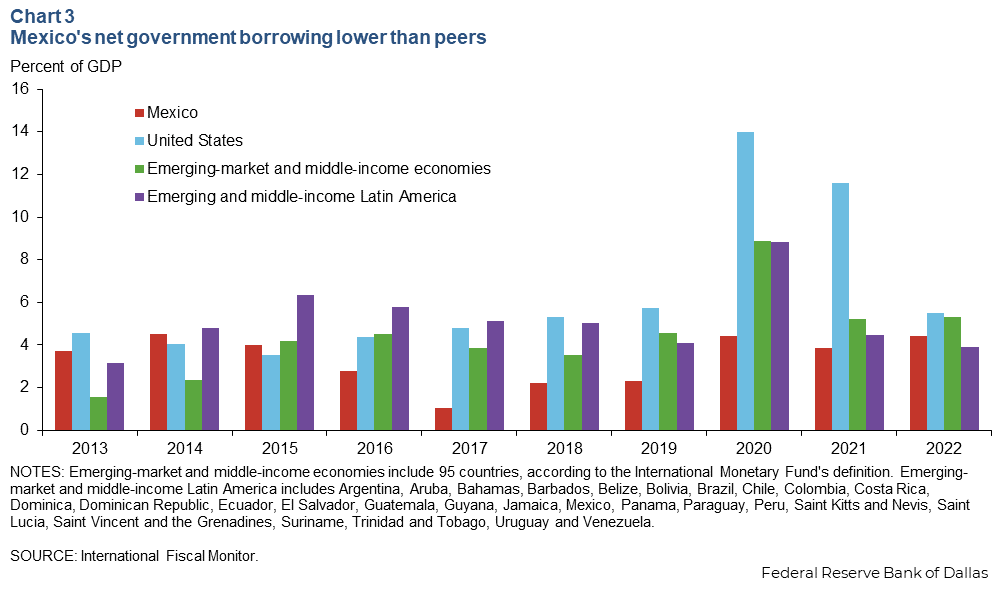

Mexico’s policy response to the pandemic stood out as the country maintained a modest fiscal deficit of about 4 percent of GDP (Chart 3). Its pandemic-related stimulus was equivalent to just 1.1 percent of GDP, less than a quarter of the average in Latin America. Such a restrictive response likely contributed to the lagged economic recovery Mexico experienced. Mexico took nine quarters for GDP to reach prepandemic levels, while Brazil took three quarters and Colombia took four.

However, Mexico’s approach reduced the credit risk of government bonds for investors. The combination of high-interest-rate carry and lower fiscal risk is often cited as underpinning investor confidence.

Mexico’s external balance benefits from close ties with the U.S.

One observable channel of the spillover between the U.S. and Mexican economies is remittances. In 2022, Mexicans living in the U.S. sent home a record $55.9 billion, representing 4.5 percent of Mexican GDP, up from 2.5 percent 10 years ago.

Remittances tend to be a stable source of income that allows an economy to reduce overseas borrowing. The current account balance determines a country’s net demand for foreign currency used to finance domestic consumption. Without large remittances, Mexico’s current account deficit would have exceeded 4 percent of GDP over the past three years, meaning the country’s demand for foreign currencies would have increased, exerting downward pressure on the peso (Chart 4). The remittances helped push Mexico’s current account deficit to 1.2 percent of GDP in 2022.

Optimism about nearshoring boosts Mexican outlook

Optimism about the prospects of nearshoring of manufacturing activities from Asia may have bolstered the peso’s strength. Mexico appears as a good alternative for companies seeking to diversify operations from China to avoid higher tariffs, improve security and bolster supply-chain resiliency by moving closer to the U.S.

This has yet to pan out in aggregate data. Foreign direct investment in Mexico was essentially flat in 2021 and 2022, averaging 2.5 percent of GDP, below the 2.7 percent average from 1999 to 2019. In first quarter 2023, foreign direct investment in Mexico increased somewhat, though most of the gain appears to be profit reinvestment rather than new investment.

While the amount of new investment doesn’t yet back up the narrative, investor optimism combined with solid macroeconomic fundamentals may be key factors.

Investor positioning played a role in the peso’s resilience

Investor positioning may have also played a role in the peso’s resilience. Foreign demand for government debt can be a sign of investor confidence in a country’s public finances. Paradoxically, a high share of foreign ownership can make the country more vulnerable to destabilizing shifts in investor sentiment.

For example, in May 2013, then-Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke made unanticipated comments that the Fed could reduce its purchases of Treasuries.

This prompted a spike in yields during what became known as the taper tantrum. At the time, foreigners held nearly 35 percent of Mexican government domestic securities. In the following month, the peso depreciated nearly 7 percent against the dollar as investors rushed to sell foreign bonds in anticipation of higher (and more attractive) rates in the U.S.

Most recently, the foreign ownership share of Mexican government debt fell from around 25 percent at the onset of the pandemic to 15 percent currently. The decline continued a trend that began with concerns about U.S.–Mexico trade following the 2016 U.S. election and Mexican economic policy leading up to the 2018 Mexican election.

Foreign investors disproportionately sold Mexican domestic debt during the pandemic as a way to reduce exposure to emerging markets because peso-denominated securities were more liquid and easier to sell than those of other emerging markets. During the ongoing U.S. tightening cycle, the low level of foreign ownership of Mexican government debt likely limited outflows and volatility.

Interestingly, the surging peso demand has not coincided with meaningful increases in foreign ownership of peso government debt or foreign bank exposure to Mexico. This suggests the peso appreciation may have been driven by investors acquiring peso exposures through derivative contracts, including over-the-counter foreign exchange swaps (for which public data is unavailable).

Return to equilibrium part of peso’s strength

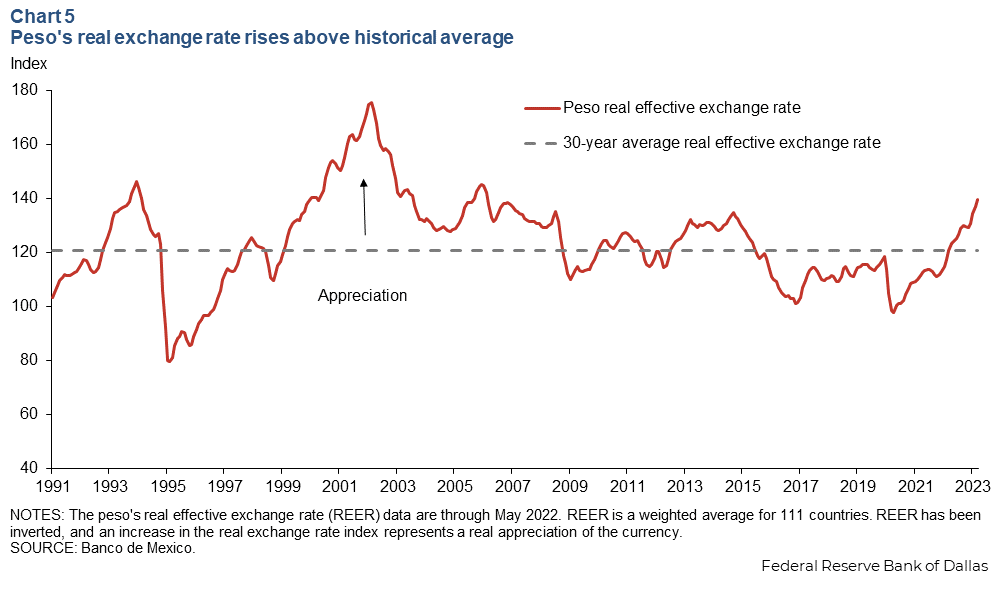

One way to evaluate an exchange rate’s long-term value is to examine the real effective exchange rate. It measures the value of a currency against a weighted average of its trading partners’ currencies while accounting for differences in rates of inflation. Absent productivity and terms-of-trade shocks, a country’s real effective exchange rate is often expected to gravitate toward its long-term average, though this adjustment can take years.

Some of the peso real effective exchange rate appreciation since 2020 may have simply been a retracement of sharp depreciation from 2015–16 (Chart 5). The value was hovering close to its 30-year average until late last year when the currency value rose above its long-run average.

Peso strength has been supported by a combination of proactive monetary policy, conservative fiscal management, close economic ties with the U.S. and positioning and valuation factors. While foreign direct investment related to nearshoring could further support the peso, it is not assured that these flows will materialize.

Meanwhile, Mexico’s real interest rate differential vis-à-vis the United States has narrowed. The peso real exchange rate is well above its long-term average, and shocks can sometimes lead to abrupt carry-trade unwinding. Finally, 2024 presidential elections in the U.S. and Mexico—perennial sources of policy uncertainty—could also prompt exchange rate volatility.

Updated 9/27/2023: This article corrects the amount of remittances Mexico received from the U.S. to $55.9 billion.

About the authors

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.