Impact of inflation shocks on foreign exchange rates reflects central bank stature

The purchasing power parity (PPP) theory of exchange rates is easily understood: A basket of goods should have the same price in different markets when that price is expressed in a common currency. This assumes individual exchange rates, absent market frictions, can freely adjust to maintain parity.

Intuitively, the currency of country A would be expected to eventually depreciate against country B’s currency in response to higher-than-expected inflation in country A. Investors increase their expectations about the long-run price level in country A, and thus the currency of country A must depreciate to ensure that the price of a basket of goods in the two countries remains the same when expressed in terms of a common currency.

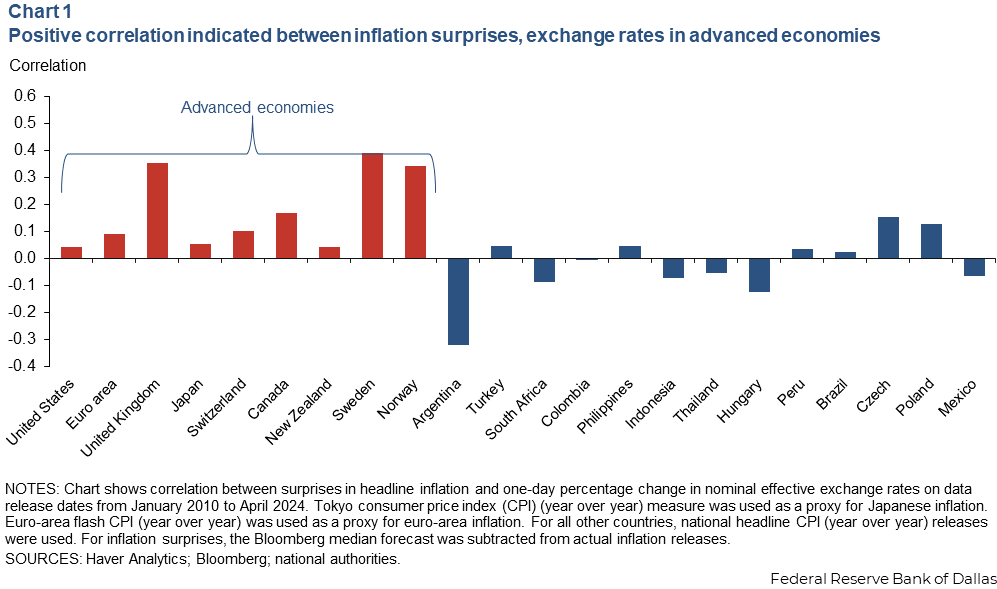

However, the relationship between market-determined exchange rates and inflation shocks is not straightforward in the short run. In advanced economies, exchange rates appreciate against a basket of its major trade partners’ currencies on days when higher-than-expected inflation surprises occur. This result seems to contrast with what the PPP theory predicts.

Additionally, the correlations are mixed in emerging markets, suggesting that advanced and emerging markets respond differently to news about inflation shocks (Chart 1).

Central bank policy reaction impacts market behavior

Economists Richard Clarida (Federal Reserve vice chairman in 2018–22) and Daniel Waldman provided a theoretical framework in a 2007 paper, “Is Bad News About Inflation Good News for the Exchange Rate?” The authors attempt to explain how “bad news” about inflation (higher-than-expected inflation) can be “good news” for the nominal exchange rate (an appreciation) as investors consider how central banks might react to the higher inflation.

Empirically, they found significant differences in foreign exchange market reaction in countries with formal inflation targeting regimes, compared with countries lacking formal targets.

If investors believe that the central bank will react to an inflation surprise by raising the policy rate, then the surprise will not change beliefs about the long-run price level, but it will alter expectations about the policy rate in the near term. The higher interest rate makes a country’s assets more attractive, leading to capital inflows that appreciate the currency. If expectations about the long-run price level are unchanged, there is no reason for the exchange rate to depreciate to ensure PPP.

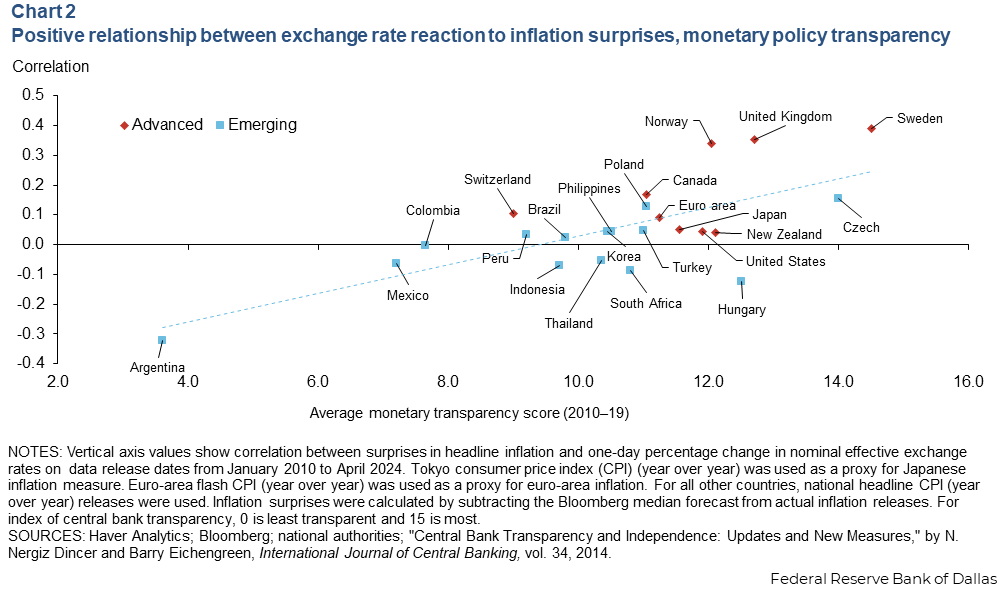

Thus, the reaction of the exchange rate to an inflation surprise should depend on beliefs about the central bank reaction.N. Nergiz Dincer and Barry Eichengreen compiled a measure of central bank transparency, where central banks are assigned a score from 0 to 15 based on the clarity of bank policy objectives and operations (15 being the highest score on the monetary policy transparency index). We can compare the correlations in Chart 1 to these transparency scores to see if more-transparent central banks also tend to have currencies that appreciate following an inflation surprise (Chart 2).

The scatterplot shows a strong positive relationship between the foreign exchange market reaction to surprise inflation and monetary policy transparency in the cross-country sample.

In other words, an exchange rate tends to appreciate in response to an upside surprise in inflation in countries with greater monetary policy transparency, as markets factor in presumed central bank reaction—the higher the transparency score, the stronger the currency appreciation.

A regression of the correlation between an inflation surprise and the exchange rate on the central bank transparency score has a coefficient of determination (R-squared) of 0.48. More simply, the level of central bank transparency explains 48 percent of the cross-country variation in the correlation between the exchange rate and inflation surprises.

A higher level of monetary policy transparency is one reason advanced economies’ correlations tend to be positive, while some countries with lower scores experience exchange-rate depreciation in response to a higher-than-expected inflation surprise.

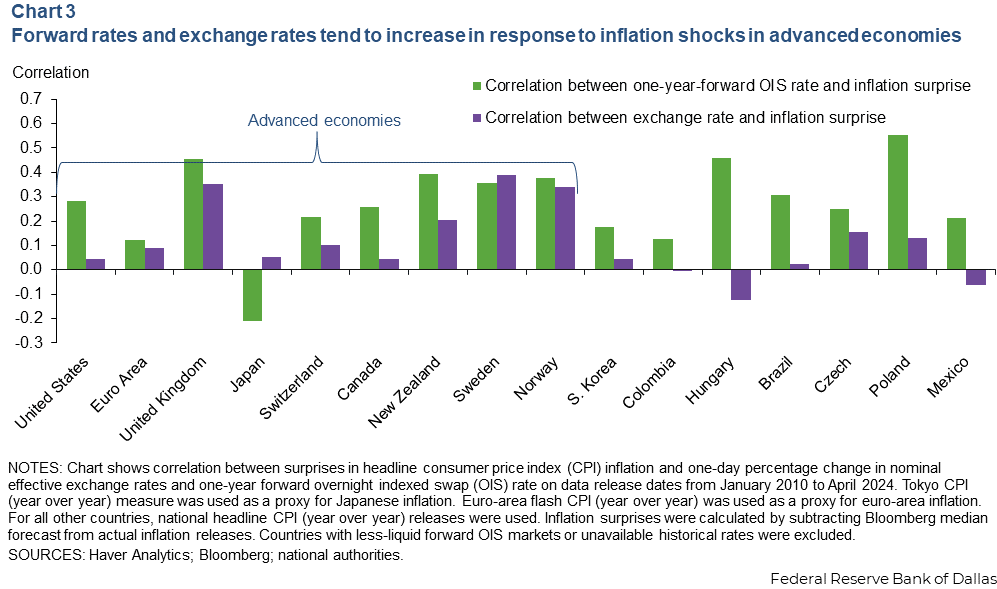

Drawing on another indicator, market expectation of central bank reaction to an inflation surprise can be inferred from the one-year-forward overnight indexed swap (OIS) rate, a market-implied proxy for where the policy rate will be one year from now. Correlations between inflation surprises and the change in one-year-forward OIS can be instructive.

Chart 3 compares the correlation, calculated from 2010 to April 2024, between the inflation surprise and the exchange rate. It separately depicts the correlation between the inflation surprise and the one-year-forward rate.

For many emerging markets, the correlation of the inflation shock with the forward rate is just as high as in advanced economies, while the correlation of the inflation shock with the nominal effective exchange rate is much lower. Thus, in advanced economies, both forward rates and the exchange rates tend to increase in response to inflation shocks. But in emerging markets, the forward rates increase but are not necessarily accompanied by an appreciation of the exchange rates amid inflation shocks.

In theory, an increase in the expected future policy rate should lead to widened interest rate differentials, all else equal. This is an important determinant of a currency’s strength in the short run.

But in some emerging markets, in which the central banks tend to have a lower monetary policy transparency score (which would imply that the central banks’ inflation targets are less credible), “bad news” on inflation may be perceived by market participants as contributing to an increase in inflation risk premium, which could lead investors to reduce exposures to the country’s bond market, and a depreciation of the currency in line with the PPP theory.

Higher inflation environment influenced market reaction to shocks

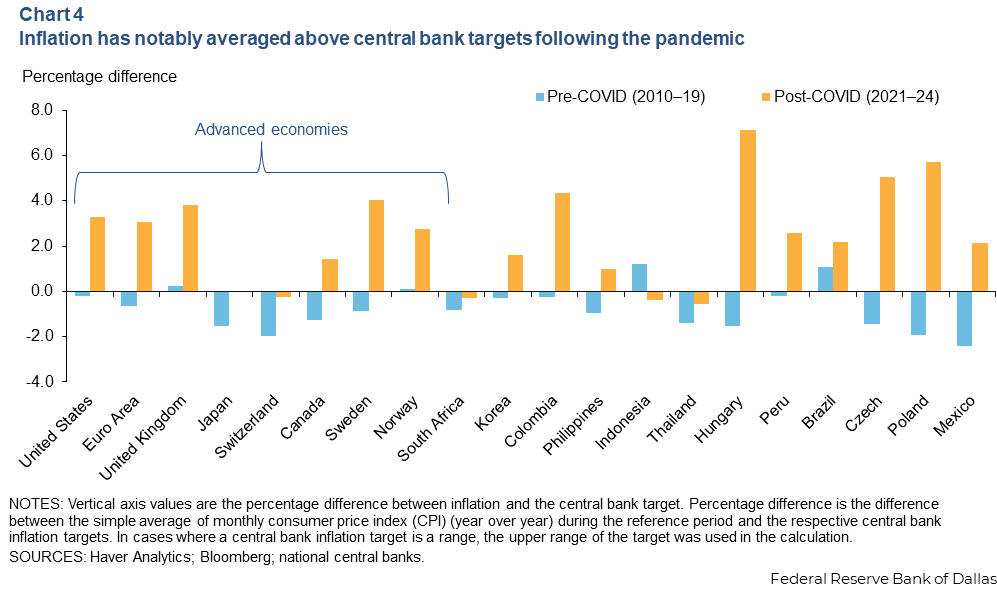

A central bank reaction function is not static and often depends on the macroeconomic environment in which the central bank operates. Chart 4 assesses a country’s inflation performance against its central bank’s target, showing the difference between the average monthly inflation (year over year) and the central bank’s inflation target. (In cases where a central bank’s target is a range, we used the upper bound of the target range. We also excluded countries without formal inflation targets and some outliers, such as Turkey and Argentina).

With a few exceptions, inflation averaged near or well below central banks’ inflation targets before the pandemic, from 2010 to 2019. Since the pandemic (we used data from January 2021 through June 2024), 15 of 20 countries experienced notably above-target inflation, and for the countries with still below-target inflation, the gaps between average inflation and their inflation target narrowed considerably.

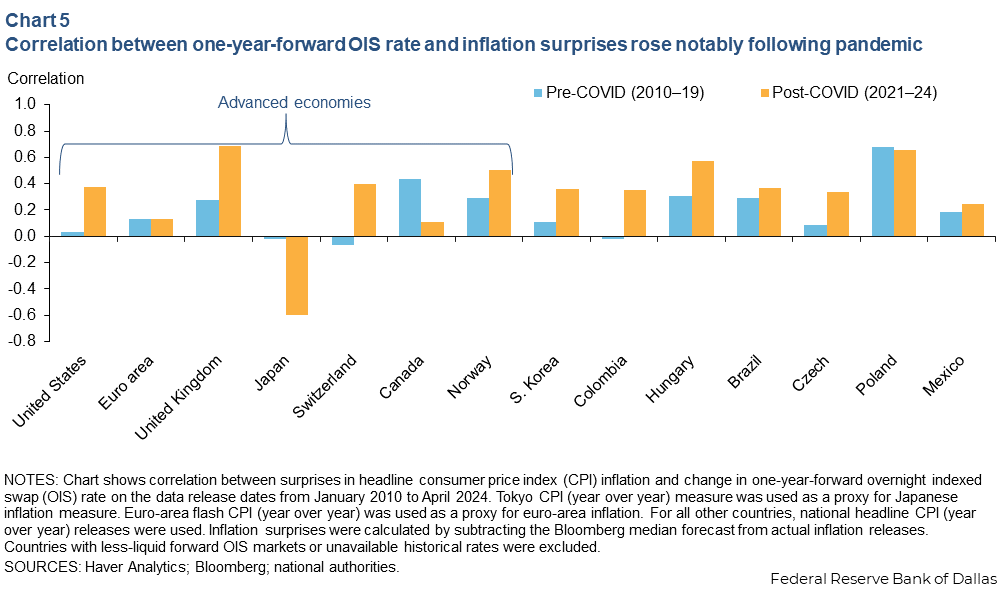

Indeed, Chart 5 shows the correlation between the one-year-forward rate and the inflation surprise in the pre- and post-COVID periods.

In a lower-inflation environment before the pandemic, many central banks, including the Federal Reserve, appeared somewhat insensitive to inflation shocks. Subdued price pressures following the Global Financial Crisis had limited upside inflation risks. Meanwhile, the policy rates in many advanced economies were pinned at or near the effective lower bound—essentially a 0 percent policy rate. Thus, there was limited room for policy rates to react to downside inflation surprises. As a result, the correlations between inflation surprises and the one-year-forward rate were low or even negative.

However, this correlation has increased notably for most countries as their central banks embarked on a policy tightening campaign, boosting rates to curb surging global inflation during the pandemic. Higher inflation and a movement of policy rates away from the effective lower bound has meant that policy rates react more forcefully to inflation surprises.

As inflation normalizes toward central bank targets, risks to the inflation outlook and central banks’ reaction functions should become more balanced (with both upside and downside risks). Thus, it’s likely that forward rates (market-implied central bank reaction) and exchange rates will continue reacting to inflation surprises, especially when involving central banks whose inflation targets are deemed relatively more credible.

About the authors